The changing faces of Miami’s Cuban community

More than a million Cubans have emigrated to Miami, the so-called capital of Latin America. As Cuba and America move to put six decades of hostilities behind them, we introduce you to three generations of exiles who have made the city their home

The first time Juan Carlos Tejedor set foot in Miami, two years ago, he says what most impressed him were the city lights: he still remembers that first sight of the skyscrapers and malls lighting up the nighttime skyline. “It was so incredibly different from Havana, which is like a cave at night,” says 48-year-old Tejedor, who was born in Cuba and grew up under the regime of Fidel and Raúl Castro. He belongs to the most recent wave of Cuban emigrants, fleeing lack of freedom, basic foodstuffs and goods, and convinced that for the time being there is no future on the island.

Unlike most of the thousands of other exiles that have made the journey to Miami over the last half century, Tejedor’s case made headlines because in Cuba, he had been a well-known television evening news presenter, but as he admits: “I had to do other jobs to boost my salary, which was minuscule.”

Tejedor had been planning his escape for some time and once he had enough money for the trip, he told his employers he was going on holiday, flew to the Caiman Islands and from there to the United States. He has never returned.

“I didn’t know anyone in Miami,” he says. “It was hard at first. Then I realized that we had all been brainwashed. We have a saying that goes, ‘In Cuba everything is forbidden and what is not forbidden is obligatory,” adds Tejedor, who now works as an assistant to Humberto Calzada, a 71-year-old painter who arrived in Miami in 1960 among the first wave who left after the Revolution. His generation believed they would soon return to Cuba: “When we arrived, we all hoped that Castro would be overthrown,” says Calzada, adding: “But after the Bay of Pigs we lost hope.”

1.2 million cubans, or 10% of the island nation, have escaped in the past six decades for political or economic reasons

Calzada and Tejedor represent the first and the last to join the Cuban exodus. Estimates suggest some 1.2 million Cubans, 10% of Cuba’s population, have escaped the island over the last six decades, the majority to Miami, which was still a relatively small town in the early 1960s. Now, thanks in large part to its Cuban community, it’s an economic powerhouse.

Mario José Penton, 29, a former priest who arrived four months ago and who is staying with relatives until his work permit comes through, says he was “blown away” by the pace of the city: “It’s so individualist, and I still can’t get over how much food they throw out at mealtimes”.

It took Penton two years to reach to the United States: he first had to journey through Guatemala and Mexico before finally reaching Laredo on the Texan border. To make the crossing, he paid $2,500 to the coyotes, or people smugglers, who are currently making a small fortune from Cuban exiles.

“When I made it over the bridge, I cried,” he says, describing the moment he got to Laredo. “I was in heaven.” At the border, he was finally able to make use of the law which grants Cubans a green card in a year and a day after stepping foot on US soil – the only nationality in the world to enjoy this privilege.

Like most of his fellow expatriates, Penton is a ferocious critic of Cuba, describing it as a “country of extremes”. “A plate of fried potatoes or a tube of toothpaste is a luxury, but there’s no problem accessing higher education. A lot of us know no other way than communism, which has really been a disaster.”

Penton, describes day to day life in Cuba as a struggle for survival. “People steal just to eat, they rob the state which is the biggest thief, stealing from the people via its ration cards.”

In 1970s miami, we were subjected to the same racism as the blacks. There were places that had signs saying ‘no children, no dogs, no Cubans

Penton also says he is struck by the Cuban authorities’ control of news and information. “I didn’t know who Celia Cruz or Yoani Sánchez were before I left,” he says, referring to the legendary salsa singer and dissident journalist, respectively. He now writes for Sánchez’s independent website 14ymedio.

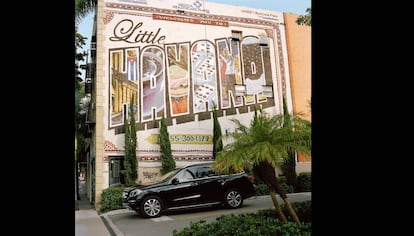

Evidence of the Cuban presence in Miami is everywhere; perhaps best represented by the Little Havana neighborhood, along with newspaper, El Nuevo Herald; as well as at the university and in the wider economy.

Among the many Cuban exiles who have contributed to that economy is Benjamín León, who arrived in 1961 with his family and set up a healthcare provider for other migrants. Today he employs more than 2,000 employees. “The Cuban community sowed the seeds that turned Miami into a big international city. Because of what we suffered firsthand, we know the value of freedom and democracy,” says the 71-year-old, who credits Cubans with “an insatiable desire to overcome obstacles”.

Raúl Martínez arrived around the same time, and went on to be mayor for 24 years of Hialeah, a city in Dade county whose population is 90% Hispanic. Miami was just a “village” back then, he says, adding: “We had to go downtown to shop because there were no shopping centers. Half of what is today Miami Beach was just dunes, and where you see big streets and avenues, then there was nothing but countryside and snakes.”

Back then, Miami was a typical southern US city with a largely white, English-speaking population. “We were subjected to the same racism as the blacks. I remember there were houses for rent with signs saying: ‘No children, no dogs, no Cubans.” Today, Miami’s mayor is Tomás Regalado, and his counterpart in Dade county is Carlos Giménez, both of Cuban origin.

Martínez recalls the Cuban community’s first steps, opening mom and pop stores, as well as how they injected life into Little Havana’s Calle Ocho; later they moved into construction, and finally began organizing themselves politically. “We gave the city its color, and we welcome people from all over the world, Asians, Russians, Spaniards, Colombians…” says Martínez, a Democrat who regrets his party’s failure to “take the Cuban community on board”, and who have largely voted Republican as a result.

For years, the Miami Cuban community has been seen as a close-knit group of intransigent exiles, obsessed solely with overthrowing Castro. But this is changing: there’s more diversity; second-generation Cubans are more progressive and are increasingly voting Democrat. This shift is reflected in Barack Obama’s decision to mend relations with Havana. “It’s an intelligent decision,” says Penton. “In 10 years the dinosaurs will be dead, and the Americans are the best thing that could happen, although Obama needs to make more demands on Raúl Castro.” Tejedor says much the same thing, albeit with less conviction: “It’s great that something positive is happening in Cuba, although I don’t know what it is yet,” he says.

But among the first wave of exiles few support Obama’s new approach to the old country. “I don’t agree with it,” says León. “Obama is dealing with the devil,” adds Calzada, the wounds of the past still raw. “It’s impossible to deal with the Castros. The younger generations think that renewing relations is a good thing, but they don’t know what really went on.”

Each wave of Cuban immigrants brings its own emotional baggage, and although each of them has helped build this great city, there is still a surprising amount of resentment between them. In the years directly after the revolution, it was the business and professional classes who came to start new lives in the United States. But for some time now, most of the Cubans arriving in Miami have scarcely a dollar to their name.

The first Cubans to arrive here still consider themselves a cut above the rest. “We left because of our political and religious beliefs, not for economic reasons,” says Oswaldo Mena, 78, who was among the first wave of exiles. “We felt Cuban but also American. We weren’t brainwashed like those who came after us. We are not the same as them and never will be”.

The most recent arrivals, like Tejedor and Penton, sense this contempt, attributing it to each generation’s need to take out its frustration on the next. “They say that we come here for economic reasons, but you can’t separate politics from economics,” argues Tejedor.

“The Cubans who have been here for a while are very hostile, they say we’re vulgar, and little better than prostitutes. But the continuing immigration is simply a reflection of the disaster in Cuba,” adds Penton.

Of all the Cubans who have come to Miami, the most stigmatized are the so-called Marielitos. In 1980, amid an economic downturn that saw thousands of Cubans take refuge in the Peruvian embassy, Castro announced that anyone who wished to could leave the country. To the regime’s surprise, around 125,000 Cubans rushed to the port of Mariel hoping to board any vessel that would take them to the United States, or to be picked up by Cubans based in Miami. At the same time, Castro took advantage of the situation to empty the country’s jails, with many prisoners joining the boatlift. Castro labelled the Marielitos as “the scum of Cuban society.”

The first thing that Juan Palacios, a 67-year-old who was among those who left in 1980, wants to make clear as he sips a coffee in Calle Ocho, is that he is not a former convict. He then turns his anger on the first generation of exiles. “They repeat what Castro said like parrots – that we are scum,” he says. “Some of them were friends of Fidel, people he allowed to leave. They despised us and they blamed us for anything bad that happened in Miami.”

There’s no denying that violent crime, drug trafficking and unemployment all rose sharply in the years that followed the arrival of the Marielitos. The city’s underworld was celebrated in series like Miami Vice and films like Scarface in which Al Pacino plays a Marielito who rises to become a drug lord. To this day, many Cubans avoid the subject.

Mirta Ojito, 52, a a Marielito herself and a journalist for US-Spanish language television station Telemundo, offers a more positive view of the Mariel boatlift, saying, “It brought the disaster of communism to people’s attention. We became a bridge between the different generations of exiles.” In her book Finding Mañana, a memoir of the Cuban exodus, she argues that if Miami is the capital of Hispanic America, it’s thanks to Cubans: all Cubans, regardless of their generation or class.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.