One in 10 US death row inmates are war veterans

High proportion of those facing execution are returned soldiers, says report

Every year since the US Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976 new statistics have attested to the fact that it is an arbitrary and discriminatory sentence. The Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) has taken a deeper look at the issue, revealing one of the most sinister realities of everyday life in the United States.

The report, which comes out on the eve of the Veterans Day public holiday, finds that 10 percent of inmates on death row are military veterans – men who will be executed by the government they served. Appeals have failed in almost all of these cases. These men are considered “the worst of the worst” and for this they deserve to die.

One third of victims killed by Iraq or Afghanistan veterans were partners or family members

The 300 veterans serving time on death row suffer from injuries sustained in combat that have conditioned their reintegration into civil society. However, these circumstances were not sufficiently emphasized – and in some cases were even ignored – during their trials.

They are men who suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): more than 800,000 Vietnam War veterans and around 175,000 soldiers who participated in Operation Desert Storm have grappled with the condition that was once known as Gulf War syndrome. More than 300,000 veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have also been diagnosed with the condition. Several studies say that only half of them received treatment last year.

A high percentage of veterans bring the war home in the form of trauma. Without diagnosis or treatment, these men and women end up self-medicating either with drugs or alcohol and end up tumbling down a self-destructive spiral of violence that also affects those around them. According to a study reported in The New York Times, one third of victims who died at the hands of Iraq or Afghanistan veterans were partners or family members.

If 300 war veterans are sitting on death row today, many others have already been executed. “At a time when sentences for capital punishment are less common, it is very alarming that so many veterans who suffered serious mental and emotional wounds while serving their country are now facing execution,” DPIC director Robert Dunham says.

Over the last 15 years, US judges have handed down fewer death penalty sentences. Even in states such as Texas and Virginia, which are at the top of the capital punishment rankings, such decisions have fallen by 80 percent. In 2014, executions fell to their lowest level in 20 years. And there will be even fewer executions in 2015, thus continuing the positive trend.

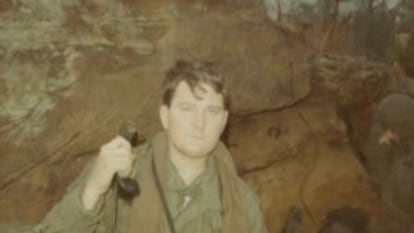

Andrew Brannan

Andrew Brannan was the first person executed in the United States this year after the California Supreme Court ratified his sentence. Brannan was a Vietnam War veteran who was abused as a child. He was executed in Georgia despite the fact that he was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other mental illnesses.

Footage from a police camera recorded Brannan as he committed the murder for which he was sentenced to death. On January 12, 1998, a police officer pulled the ex-soldier over for speeding while driving his van. The video shows Brannan getting out of his vehicle – in most US jurisdictions a driver is prohibited from exiting the car when a police officer stops him on the road – and then starting to behave erratically.

“Fuck you! I’m a Vietnam War veteran,” he shouts menacingly at the officer while disobeying his orders. Then Brannan returns to his van, pulls out a gun and begins to shoot. Officer Kyle Dinkheller returns fire.

Dinkheller was struck nine times before dying at the scene. Brannan suffered one gunshot wound to the abdomen. These images are still shown during training sessions at police academies today.

John Allen Muhammad

Known as the D.C. Sniper, this Gulf War veteran was sentenced to death for killing 10 people, most of them in the nation’s capital. His victims were chosen at random. He was executed in 2009.

His ex-wife described how Muhammad, a decorated soldier, gradually became a different person after returning from the war. “Before going to Saudi, he was the life of the party... He came back confused, moody... and was diagnosed with PTSD. He was a proud man -- not one to say, ‘I need help.’”

Eddie Ray Routh

This marine's case shows that there are several considerations when it comes time to hand down a sentence. Routh killed Chris Kyle, a former Navy SEAL and the most lethal marksman in American history whose story was immortalized in the Clint Eastwood film American Sniper.

Kyle struggled to settle back into civilian life upon his return and decided to spend time helping other soldiers who had similar experiences. Routh, who suffered from mental illness, was one of those soldiers. He shot Kyle while they were practicing at a shooting range in Odessa, Texas. Routh was sentenced to life in prison in February 2015.

John Cunningham

In July 2015, the California Supreme Court unanimously upheld the death sentence of John Cunningham, another Vietnam War veteran who was also abused as a child. Cunningham was sentenced to death for killing three people where he once worked. The ex-soldier confessed to the crime, said he felt relieved that he had been caught, and made references to nightmares and experiences from Vietnam. He offered no defense during the trial. Although his attorney presented evidence to attest to his precarious mental state, the prosecution argued that other veterans who had similar experiences did not turn to crime. The State of California has not yet announced the date of his execution.

English version by Dyane Jean François Fils.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.