The last days of Pablo Neruda, as told by his driver and secretary

Chilean poet assured Manuel Araya he was injected in the stomach hours before he died

Four hours before Pablo Neruda died, allegedly from prostate cancer, the man who was taking care of him found himself unable to complete one of his last tasks: to buy his boss medicine to “alleviate the poet’s pain.”

The newly installed military dictatorship in Chile prevented him from doing so.

All of Neruda’s collaborators were forced to disappear. I am the only major one left”

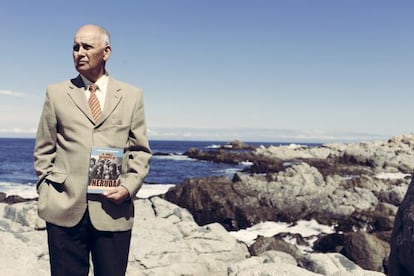

Forty-two years later, Manuel Araya Osorio is out to complete his last mission: to help prove that the Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet was poisoned while he stayed at a Santiago hospital, days before he was expected to fly into exile.

Araya, now 69, is the only known surviving witness who can recall Neruda’s final days before his death on September 23, 1973. He is convinced that Neruda didn’t die at age 69 from prostate cancer – as the official record states – but had been murdered by the military.

At the time, he was 27 years old, and had been working as the poet’s driver and personal secretary. The day he left Santa María Hospital, where Neruda had been admitted, four armed military officers stopped him.

“I am the secretary, driver and the person who is taking care of Mr Pablo Neruda – the Nobel laureate in literature,” he recalled telling them. “And I am on my way to buy him some medicine. It is urgent.”

According to Araya, they grabbed him from the white Fiat 125 vehicle he was driving, beat him up and shot him in the leg. He was then taken to police headquarters, where he was interrogated and tortured.

Later, he was transferred to Santiago’s National Stadium, where the Augusto Pinochet regime held scores of political prisoners who would later be killed or forced to disappear.

Manuel, let me tell you, Pablito died last night at 10.30”

Araya spent the night at the stadium. The following day Santiago Archbishop Raúl Silva Henríquez recognized him.

“Manuel, let me tell you, Pablito died last night at 10.30.”

“Murderers!” the driver yelled back.

It wasn’t until after 42 days that Araya was freed from custody, with the archbishop’s help. But it was just the beginning of a long nightmare.

“All of Neruda’s collaborators were forced to disappear. I am the only major one left of that group that is still alive,” Araya said in a recent phone interview from his home in Chile.

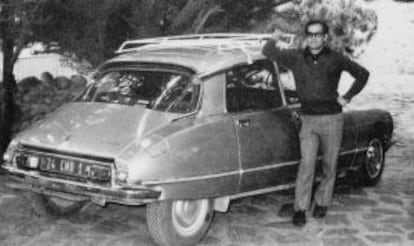

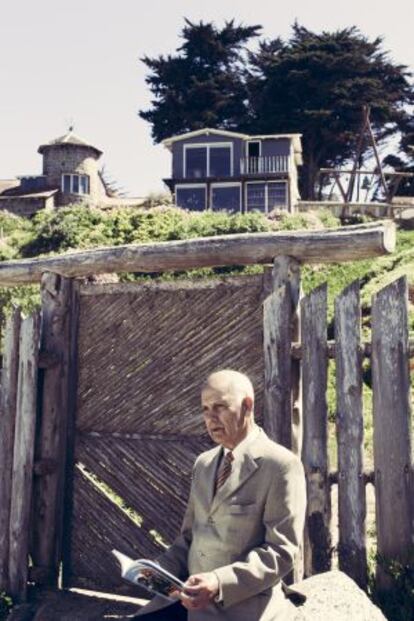

Araya began working for Neruda when the poet returned to Chile from France in 1972 to help his friend, President Salvador Allende. He stayed the with poet and his family in Isla Negra, on the Pacific coast.

Neruda had been diagnosed with prostate cancer but “wasn’t agonizing,” Araya said, adding that the poet also suffered from phlebitis in his right leg and sometimes walked with a limp.

Following his release from custody, Araya said that he returned to Santiago so as not to put his own family in danger.

“I lived nearly hidden with friends at their house. I had no driver’s license or national identity card. No one would give me a job until 1977 when I started working as a taxi driver. The dictatorship ended in 1990 and two years later I started working for [bus line] Pullmanbus in the administrative area, until I retired in 2006,” he said.

The driver continued to have contact with Neruda’s widow and third wife, Matilde Urrutia, who died in 1985. But their relationship soured over Araya’s insistence that Neruda had been poisoned.

He even tried to get former President Ricardo Lagos and others to hear his story but “no one would listen to me.”

“Maybe they were scared, but I really don’t know why.”

It wasn’t until 2011, when a journalist from the Mexican news magazine Proceso interviewed him, that an official investigation got underway at the request of the Chilean Communist Party (PCC).

Two years later, a judge ordered Neruda’s remains to be exhumed but forensic experts found no traces of poison.

But fresh revelations have now surfaced in a book by Alicante historian Mario Amorós, entitled Neruda. El príncipe de los poetas (or, Neruda: The prince of poets), which went on sale this week in Spain.

Among the new facts – as EL PAÍS first reported – is a Chilean Interior Ministry document handed over to investigating Judge Mario Carroza Espinosa on March 25 that states that Neruda did not die as a “consequence of the prostate cancer he had,” but that “it was clearly possible and highly likely” that he was killed as a result of “the intervention of third parties.”

I had loosened some wires on his television set so he couldn’t see the coup taking place”

Judge Carroza is now waiting for the results of a final forensic examination by a team of international experts who are looking into traces of the staphylococcus aureus bacteria found in Neruda’s remains. If genetically altered, the bacteria could be lethal if given at a high dosages.

Scientists are trying to determine the DNA make-up of the bacteria and conclude if it had been altered at a military base, taking into account that the Pinochet dictatorship used chemical weapons to help get rid of its opponents, Carroza has said.

A ruling in the case is expected by March 2016, according to the forensic investigators.

On September 11, 1973 – the day of the bloody coup that overthrew President Allende – Neruda summoned his driver before dawn to tell him that he had heard on an Argentinean radio station of a possible military uprising. The poet was at home in Isla Negra.

When we returned, Neruda’s face was red: ‘They injected me in my stomach and I am burning up inside’”

“I had loosened some wires on his television so he couldn’t see what was happening,” Araya recalled. “The entire country was under curfew. ‘They are going to kill us all,’ don Pablo said.”

The following day, they saw a navy warship off the coast of Isla Negra. Mexico’s ambassador to Chile had offered Neruda asylum.

On September 14, military officers entered his home and searched the premises.

“We were all scared,” recalled Araya. “The military didn’t want to give him a safe conduct pass, so he had to say that he was sick and needed to leave to seek treatment; the only way to get him out was on humanitarian grounds.”

On September 19, Neruda, his driver and wife all traveled to Santiago by car; they were stopped on several occasions by military officers who threatened and insulted them.

We never let Neruda out of our sight. Every night I slept in a chair while Matilde slept at entrance of his room”

“It took us five hours when it should have taken us two,” he said. “We arrived at 6pm but never let Neruda out of our sight. Every night I slept in a chair while Matilde slept at entrance of his room.”

On September 22, Neruda was granted a safe conduct pass and he agreed with Mexican ambassador Gonzalo Martínez Corbalá that he would fly to Mexico two days later.

“The next day, Sunday September 23, he asked me to return to Isla Negra with La patoja, his nickname for Matilde, to fetch the luggage. We went and his stepsister Laurita stayed with him.

“Nearly on our way back, at around 4pm, he called the Santa Helena inn to ask them to tell Matilde to rush on back. When we returned, Neruda’s face was red: ‘They injected me in my stomach and I am burning up inside’.”

Araya said that he grabbed a wet towel and placed it on his stomach while a doctor entered the room and told him to go out any purchase a drug used to treat gout.

Two vehicles intercepted me and four armed men got out and began beating me”

The driver never returned to the hospital.

“When I was driving in my car two vehicles intercepted me and four armed men got out and began beating me, saying: ‘You son-of-a-bitch! We’re going to kill all the Communists!’ They took me to police headquarters where they interrogated and tortured me.

“They wanted to know where the Communist leaders were hiding, and who held meetings with Neruda. I told them that Neruda only met with other writers.

“In the end, they took me to the National Stadium and the following day Archbishop Silva Henríquez broke the news,” Araya recalled.

Now, the retired driver is awaiting Judge Carroza’s final ruling in the Neruda case. But his last task for his former boss has been completed – someone paid attention to his story.

“I am more serene than ever,” he concludes.

English version by Martin Delfín.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.