A modern generation of matadors

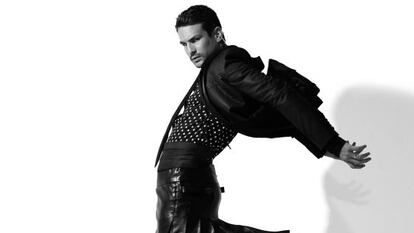

Cayetano is among a new breed of bullfighters unafraid to defend their profession

A married bullfighter is a finished bullfighter. But this old saying does not apply to Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez – and it’s not because he plans to remain single all his life.

Instead it’s because he represents a unique case in the profession: he was 29 by the time he became a full-fledged matador, and waited until the age of 38 before deciding to get married.

The wedding will take place on November 6 in Mairena del Alcor (Seville), the birthplace of his fiancée, television presenter and former Miss Spain, Eva González.

I think that the world of bullfighting also needs a change. We need more unity and better organization”

Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez

The event is expected to attract hordes of paparazzi, but then Cayetano has already learned to live with constant attention from photographers, and even to throw them off the trail like he did during his recent “bachelor party tour” of New York, Mexico, Paris, Milan and Lisbon.

The trip is evidence of his own cosmopolitan journey through life. Cayetano speaks several languages, has modeled for Armani, traveled the globe and likes to collect contemporary art.

And this year, he has returned to the ring to stay. His success in Ronda (Málaga) cleared up any existing doubts over his bullfighting future.

“I’m not here on a visit,” he says. “Bullfighting is my profession, my calling and my life. Very often, the efforts and sacrifices that go into it get ignored.”

Cayetano knows how to strike a pose and how to express himself. He speaks slowly – just as he tackles the bulls – and with a deep baritone voice.

“Bulls were the first things that taught me to hate. A bull took my father [matador Francisco Rivera, ‘Paquirri’] away when I was seven years old,” he says. “At that age, you don’t understand anything. In time, through the bullfighting education I received, I learned to understand the trade, to respect it, to love it and even to devote my life and time to a profession that has taken so much from me, but that has given me so much in return.”

This confession comes coupled with a sense of disbelief over the current rise of the anti-bullfighting movement in Spain. Cayetano regrets that the practice has become an inflammatory subject in debates over politics and regional identity. He is “angry and sad” that leftist Madrid Mayor Manuela Carmena has withdrawn public support for the local bullfighting school in a show of belligerence against the industry.

Cayetano notes that Madrid is the world capital of bullfighting, drawing a million spectators to Las Ventas bullring this year. “I don’t understand how animal activists mean to protect bulls by prohibiting bullfights. Because that way leads to the animal’s extinction,” he says about the Spanish fighting bull, which is bred for its aggressive character.

Cayetano and Eva González’s wedding announcement: “We want to share our happiness with you... We’re getting married! And it will be on November 6 in Mairena del Alcor!!”

“I risk my life when I kill a bull, and I think that gesture awards the bull a lot more dignity than what it would find at a slaughterhouse. And in these times of such environmental awareness, it is essential to recognize that the bulls and the dehesas [free-range estates where they are bred] contribute an ecological wealth that would be unthinkable without the fights.”

“I don’t like to talk about economics to defend them,” he adds. “But there is evidence to show the impact of an industry that employs 200,000 people and contributes a lot more money to the government than it receives.”

Cayetano has requested for this interview to take place at a photo studio outside Madrid. There with him is Curro Vázquez, his teacher, mentor, uncle, agent, and also best man at his upcoming wedding.

Asked why he has decided to get married, the matador is vehement. “These are important decisions that you take in life, and when you find the person that you want to share your life and start a family with, I think it’s the natural step,” he says. “I grew up in a Catholic culture and I like it. That is why we decided to take the step. I think the time is right, and I am completely convinced.”

Cayetano is not to be deterred by the exhausting planning involved in a celebration that is certain to bring the town Mairena del Alcor under siege from the press, particularly the gossip magazines.

“I have learned to try to live with that media exposure. But you never get used to it, because we are all people, we have our good days and our bad days, and we like our privacy. But I also understand that I am a public figure because of my profession. That’s part of my life, but I ask for some respect so that certain lines are not crossed.”

Cayetano himself has crossed many lines, however. He is a bullfighter whose face appears on ads in bus shelters, promotes Loewe perfume, and has served as the image of Giorgio Armani.

Genetics put a matador’s sword in his hands: he is the son, brother, nephew, grandson and great-grandson of bullfighters – his father Paquirri was killed in the ring in 1984. But Cayetano’s social involvement – a fact that the bullfighting orthodoxy regards with mistrust – has turned him into the obvious vehicle for the industry to communicate with the outside world.

“I do feel that I have a responsibility,” he admits. “And I am ready to give it my all in order to defend my world with pride and honor. Sometimes I feel misunderstood. The anti-bullfighting movement is triggered by political motives or else by ignorance. And that ignorance stems from a lack of opportunity or interest. I don’t ask for people to like it. I ask them to respect it.”

Cayetano is interested in politics. He would vote for the center-right Popular Party (PP) if his decision depended entirely on its position on the bullfighting issue. But he is still unsure how he will vote at the upcoming general elections in Spain on December 20. He sympathizes with the emerging center-right party Ciudadanos, and says he likes the common sense and sincerity displayed by its leader Albert Rivera – but not enough to have made up his mind yet. First comes the wedding, then the election.

“The appearance of new parties has done more than break the two-party system,” he says. “It has also breathed new life into politics, making it more interesting. It’s shaken the foundations. I think that the world of bullfighting also needs a change. We need more unity and better organization, and a less partisan vision of what it represents. But I am sure it will never disappear. It’s a unique esthetic and artistic expression.”

English version by Susana Urra.

The Brando of bullfighting

When José Mari Manzanares – known to almost everyone as Josemari – has a date at the ring, he needs to leave the hotel before everyone else in his team because it takes him longer to get there. That is because of the bevy of admirers, mostly young women, waiting to pounce on the 33-year-old matador at the door.

That’s the trouble with being the Marlon Brando of the bullfighting world, and the price to pay for someone with almost insulting good looks, natural elegance, and facial features that others can only dream about.

This son of a bullfighter is aware of his own charms, and steps into the ring as if he were stepping on to a catwalk. A thoroughly modern matador, he has his own website, Facebook page and Twitter account.

Someone like this, famous by birth and handsome by nature, who wears glittering outfits and makes women swoon, could not go unnoticed by the fashion industry. Josemari is a good bullfighter who has allowed himself to be seduced by the vaporous appeal of his own image. This year, he has been more successful as a model than as a bullfighter, and been seen more often in the company of beautiful actresses than on the shoulders of aficionados. He has worked with famous photographers, worn make-up and hair gel, donned expensive suits by luxury designers, and shown off his svelte body on magazine covers, staring at the camera with a look of seductive sadness.

Josemari is still mourning the death of his father in October of last year, and has worn black at the 44 fights he has fought since then. A psychiatrist friend helps him deal with his emotions. Deep down, like all bullfighters, he is an odd guy who admits to major mood swings, claiming that the bull’s gaze makes him feel the fragility of life very close and personal.

Josemari has two children and a wife who experiences mortal fear every time he steps out into a ring and, perhaps, some misgivings every time she is forced to share her husband with so many other women’s fantasies. A good friend who knows him well said he understands why Josemari wants to work as a model: “that way he makes money without feeling fear.” But he has asked him to remember that “you are famous through bullfighting.”

“The day he stops fighting, he won’t be getting any more calls for photo ops.”

The eccentric artist

José Antonio Morante de la Puebla, another bullfighter from Seville, does not lend his face to any product, nor does he appear standing next to famous models. But he still takes good care of his image, which is studiously untidy.

As an artist-bullfighter with a unique style that makes many regard him as a genius, Morante is able to turn a classic cape move, the verónica, into a work of fine art one day, then show up the next dressed as Salvador Dalí, sporting a long mustache, a crazed look in his eyes, and the name "Salvador" and some flowers painted across his bare torso in order to advertise the a series of bullfights in Zaragoza.

Like Dalí, Morante is also an odd guy at the mercy of psychological ups and downs that have an impact on his life and work. Bohemian and unpredictable, he can be talkative or quiet, and has been known to borrow a hose to water down the dusty ring in Alicante, file a complaint against an animal rights activist who called him a "murderer," and to dress up as a lynx to promote the local fiestas in Huelva.

He is an artist who feels and looks different – classical and modern, romantic and eccentric, strange and singular, but never vulgar.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.