Orhan Pamuk: A love for Istanbul

The Nobel-winning Turkish author’s new novel imbues everyday stories with an epic touch

Orhan Pamuk (Istanbul, 1952) has written another monumental novel, A Strangeness in My Mind, which comes after The Museum of Innocence, published in 2009. With intelligent and moving meticulousness, the Turkish Nobel Prize-winner tells of 40 years in the life of a humble Istanbul street vendor. It’s a book about happiness (or the lack of it), and about time. While reading it, it’s impossible not to feel that its protagonist, Mevlut, embodies the very Istanbul he describes, and, in fact, when one travels to Istanbul and listens to its racket and rejoicing, it seems obvious that Pamuk has made any and all of these characters stand up in his fiction on these old streets. We talk in the house Pamuk lives in, in Bujukada, the beautiful island his parents would take him to from the day he was born. He still spends his summers there, writing in a peace that’s only disturbed by “the soft passing of time,” marked by the shadows the sun throws over his bare balcony. Before we talked he offered us watermelon and apricots. He looks happy, as if he’s fallen in love, and not only with literature.

Question. You say in this book that we have to believe in the novel when we are reading it. Why is it so important to believe in what you are reading?

Answer. Because literature, whether it is fantastic or realistic, works with what Samuel Taylor Coleridge called suspension of disbelief. If you’re a cynical person, if you are not a sincere believer in the strength of literature, then you should avoid reading books. In the end there is a very old-fashioned side to reading novels in our age – blogs, internet, so much information and so much humanity. Why read novels? Because we believe in the power of literature. We’re not cynical or sarcastic or suspicious about it. Literature works with intentionally well-meaning readers. You say I’m going to give 10 hours to this Istanbul street vendor’s life. Then you’re not sarcastic any more. You’re with the characters and you take the writer’s work for granted. You should not take it for granted and not question it, at least at the beginning.

Q. And as a reader, you have the illusion that the story goes on. You’re in the story but not because you want the story to be told in a second, but to carry on like it were your own life.

A. The trick about the kind of novel I have written is the pace, or the unfolding of the story. If you go too fast, it gets to be too dramatic; if it gets too detailed, it gets too long. Mevlut’s story covers 40 years of working-class people’s lives in Istanbul and it also has many characters. Mevlut is at the center, harmonizing their stories in a way that gives the illusion that this is also how life unfolds. Slowness, and then suddenly it gets fast. In a way this is a realistic 19th-century kind of novel, where the pace of the storytelling mimics the pace of life in a way.

Q. The pace of life also has to do with the details, and even if you don’t want them to be too detailed, they are there because they take the reader to the center of the novel.

A. There are many characters, and we hear their stories. The joy of enjoying a novel also comes as you read the stories of many characters. You ask questions about what is important – why is he telling me this? Why can’t Mevlut get rich? These problems address the main philosophical, anthropological questions of the time.

Q. At one point your novel suddenly becomes a metaphor of time, of happiness, of pain, of greediness. It is very obvious that you’re telling a metaphor of time.

A. The novel has an ambitious epic concern, that of representing the regular citizen’s life in Istanbul between the 1970s and today. And also the novel has a metaphysical tone, that of the solitary, introverted Mevlut who experiences the strangeness of his mind. The questions are: what makes us happy? That our intentions are satisfied, or that we have the capacity to be happy with whatever is given to us? How important is the inner fantastic mental world we may all have in our minds? Some of us are introverted, some of us are more social. The interesting thing about Mevlut is that he is, in many ways, a good-natured social man, but there is also an inner world to him that is different, that is not easy to pin down, that he only shares with his readers.

Q. You have said that you have to give us readers the pleasure of forming mental images out of the words of the novel. Very soon you see Mevlut in the streets of Istanbul, selling boza [a popular fermented beverage] in a peculiar way, it’s very visual in the book.

A. First, I argue that part of the novel works best when the writer has a picture in his mind. And what is that picture? Istanbul of the 1970s and 1980s, the chemistry of its streets, its poverty, its politically repressive ways, its provinciality and its richness. It’s the way it is poor and repressed, but there is also immense potential. These are the ideas, then there are the details. Then I have to pass it to the readers through words. Mevlut is a visual person. He, like me, enjoys to put in words what he enjoys visually. For me a novel works best if you address the reader’s visuality. I am happy when my readers say to me, Mr Pamuk, I’ve read your novel and it felt like a movie. It’s a good compliment and I’m writing to get that compliment – meaning, first I try to evoke the scene in the reader’s imagination through pictures.

Q. But you also want the reader to feel affection for the characters.

A. Yes. Unfortunately it’s like that. The reader – and I am also one of these readers – wants to have a character that he or she would identify with, would feel close to, would argue with and, essentially, feel affection for. Bertolt Brecht would not have liked this idea. He doesn’t care about that sentimentality. But I care about it. My relationship between me and the reader is perhaps like my relationship between me and Mevlut. In a way I am saying to the reader: hold my hand, I’ll show you the world of Istanbul, this time with Mevlut. I want the reader to feel close to Mevlut. I want to leave the reader with Mevlut. And that’s why I need this compassionate understanding. And Mevlut is also a loveable guy. First, because he’s lower class, and unsuccessful. Second, because he’s well-meaning, and third perhaps he’s not cynical, he’s intelligent, perceptive and of a different mind. What I want is for the reader to slowly rely on and care about the fact that he has a strange mind, he sees things differently. We begin to love a character. Not only is he a good ethical person but he sees the familiar words in an unfamiliar, strange way. That’s the most precious thing a novel character can give us. A novel is joyful for me if it takes me to the regular world but shows me many irregular, strange things.

Q. Were you thinking about yourself when you were describing Mevlut?

A. Yes. There is a Mevlut in me in the sense that he is introverted. In spite of all the efforts to be very social and normal, somehow you realize you are different. Compared to me, Mevlut is more optimistic. But the essential difference between me and Mevlut is of course that I am upper-middle class while Mevlut is working class. He is in many ways a typical working-class person of Turkey. In that sense Mevlut has the qualities of an everyman.

Q. And what are the characteristics of a middle-class person in Turkey?

A. Let’s have a look at Mevlut’s life. He wants to be religious, he is afraid of his God, but he also wants to be modern, too. And there is a contradiction there. He wants to belong to his childhood village community and… to continue behaving like that. But he himself betrays these things, these values, and attempts various capitalistic things, which if he sees in others, he criticizes. Mevlut is a very good guy in many ways. He is surrounded by pious people, nationalists, radicals but wants to continue like a normal Turkish working-class citizen. In 500 pages we see him always concerned about money – not because he is greedy but because he wants a decent life. Another important thing that makes him an everyman of Turkey is his aim to have a house of his own.

Q. But he remains poor. That fact is very important in the novel.

A. And the novel is perhaps implying that Mevlut remains poor because, as Mevlut himself says, he is a good guy, he never once shows too much ambition, too much cheating and scheming. One of the reasons he is not rich is he is not a social organizer, a successful organizer – perhaps because he has a rich inner life and he is a bit dreamy.

Q. Would you say that Mevlut is a brave man?

A. Brave? Not very brave. Mevlut sees danger and immediately avoids it. I am not being critical of him here. He would not take a risk for a social, ethical principle. Mevlut always – that’s how I feel about him – would be concerned about protecting his family, his children, his business, then he would care about values, this or that. But on the other hand, let me give you an example: when he loses his pilaf rice cart, they offer him a free one, but as he doesn’t like the picture of the woman belly-dancing, he refuses it. In that sense Mevlut is not a money-greedy person, in that I think he’s not very typical. He is distinct and admirable. That’s why I also think that people will follow his story.

Q. Do you think this novel is like a love song to Istanbul, sung by Mevlut?

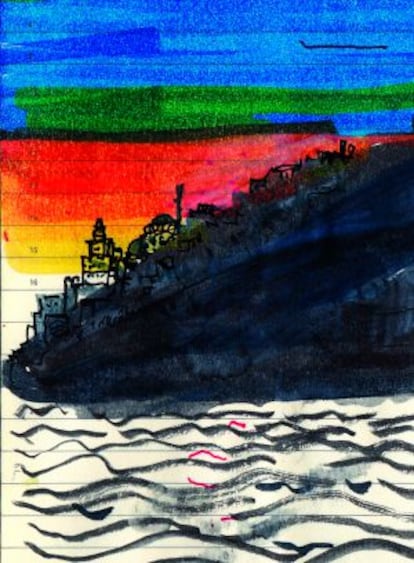

A. I wouldn’t say love but I would say respect. Here what we see is an historian’s Istanbul. The Istanbul described here is not very beautiful and admirable and touristy but if there is love here, the love is about my attachment to the development of the city, its shops, its objects, its food, how the food is bottled, put in cartons, the distribution of food, films, newspapers, the development of daily cultural life in Istanbul. We always talk about cities in big words but most of the time we talk about its landscapes, its historical moments, its meaning, its historical places and so on. We talk about the city in capital letters. Here I talk about the city in a more feminine way maybe, that of kitchens, what we eat, how women work, what’s happening in the kitchen, drawing-room, how the food is prepared – I care about the identity of the city. The way it changes. Not only on the maps and big monuments, but the small history of daily life, how we survive, how yogurt used to be sold via street vendors, it was bottled, then it was put in plastic cups. This novel is also an attempt to raise the mini histories, daily life histories to an epic scale. The main story here is the story of little lives, little kitchens, little rooms, streets, the chemistry of the streets formed by little groups, little shops.

Q. Little conversations…

A. Yes, little petty conversations, which I care about.

Q. After The Museum of Innocence, this is the book in which you put into practice the theory you outlaid in your essay The Naïve and the Sentimental Novelist. For instance, you say the art of the novel becomes political not when the author expresses political opinions but when he makes an effort to understand someone, and identify somebody who has nothing to do with his culture, class or genre. This means feeling compassion before making a cultural or political judgment.

A. Yes.

Q. I think it’s very obvious that you’re writing a book that you have thought out very clearly. Not just about ideas that came to you by coincidence. You wanted to write this book in particular.

A. Yes. There are many aspects to this situation. First, I did a lot of interviews with people like Mevlut. I have found the old street vendors of Istanbul and did interviews with them. Not only street vendors, waiters, electricity bill collectors, kebab shop workers, rice sellers. At the heart of this book there is an almost journalistic attempt to chronicle everything. And after doing 10 or 15 interviews, you begin to see that all lives are so different from each other and so similar. The person comes from poor rural Anatolia when he is 12 because most of the time there are no secondary schools there, most of the time the father is already in town making money and sending money during the winter and coming for harvest during the summer. These details are there. But then you begin to think that the distinct individuality of each person is also dramatic. One of the prejudices of 19th-century novels was that at the beginning the art of the novel put the individuality of the upper-class person on a pedestal. Tolstoy, an aristocrat, Proust, an aristocrat, Dostoyevsky a middle-class demonic intellectual, but working-class people have always been associated with lack of individuality and depth, or a sort of gray area where novelists did not know what to do, except feel pity, sorrow and guilt. My essential ethical and esthetic problem here is to make Mevlut as heavily embedded in “working classness,” whatever that is, but also to make him an individual, to make him real and to make his individuality the most respectable thing about Mevlut. That was my esthetic challenge. When I began to take that road, I could have represented the working class as John Steinbeck did in The Grapes of Wrath. We all cry, and we learn a lot, yes. But that is a social description and perhaps I have written a social novel, but what is important for me when the reader closes this, after 10 hours of following Mevlut, is that they say it’s not Mevlut’s poverty any more, it’s his individuality, his strangeness. If I feel that my reader is only weeping, I don’t like it. I want him smiling and respecting the individuality of the character.

Q. And feeling angry?

A. Yes, unhappy. That was a challenge. I am happy that my Turkish readers, most of them, are not people like Mevlut. They are more middle class, upper-middle class, they are happy with the accuracy of my description. I did my homework in that sense.

Q. It is a way of writing that is, as you suggested, journalistic in a way because the characters sometimes talk to the reader.

A. Oh, yes. That’s Brechtian. I don’t agree with Brecht’s anti-sentimentalism. I need, I think, readers to identify with fictitious characters but, on the other hand, one thing I learned from Brecht – which is also reflected in My Name is Red – is that the characters directly address the reader and whisper things directly to them that the other characters don’t know.

Q. You have said that over the last 40 years of writing novels and putting yourself in the skin of others, you have created a more complex and elaborate version of yourself.

A. OK, this has two results. First, you understand that part of writing novels is a very moral thing. You want to understand people who are not like you. You want to identify people who are not you, other people. It’s a political gesture. Novels are not self-expression. At least half of the energy is not self-expressive, but it is directed at understanding people who are not like you. So if you do that for 40 years, if you put your daily energy for 40 years into understanding people like Mevlut, who is essentially poor, from a different culture and has different mental and economic problems, then you also learn to be modest, to be respectful of the lives of others. Writing novels for 40 years taught me to be more respectful, more kind, more delicate, more careful paying attention to the details of their lives. Maybe I should tell you that 40 years ago when I began writing fiction as an upper-middle-class boy in Turkey, my previous generation of writers – and, what’s more, family, my uncles and aunts – you know what they used to tell me? Orhan, you’re 25 and you are writing novels. You don’t know anything about life. You shouldn’t write novels. Novels should be written after 40 when you learn about life. And at the time I used to say: these people they don’t know about Kafka, Borges, Poe and Calvino, and I’m going to write novels like that – and that would be my answer. Novels are not about getting old and knowing what life is about. Novels are about expressing yourself about metaphysics, about what you think life is, and you can know the answers, even when you are 18. Now, 40 years later, I agree with all those uncles and aunts.

Q. Can we see Mevlut today in the streets?

A. Yes. In fact, the novel is based on people like Mevlut who I interviewed. I’ll tell you a funny story. The novel was published the first week of December last year; this is my biggest-ever-selling novel in Turkey. On New Year’s Eve we were sitting with friends. And suddenly we heard someone in the street shouting “boza.” Then we went to the back room and we brought him up and he was more or less like Mevlut. All yoghurt and boza sellers in Istanbul come from one particular region, and he too was from that region, so he was like Mevlut in all details. Then one of my friends said, “Did you know there is a novel that has been published where the character sells boza? Have sales gone up?” He didn’t know about the novel but he knew that the TV was talking about boza because of the success of the novel. So, yes, there are still Mevlut-like people in the streets of Istanbul, selling boza. Their best years were the 1970s. The people I interviewed told me that in the 1970s there were perhaps 2,000 boza sellers in the streets each night, but now the numbers have gone down because it is sold in bottles. As I argue in the book, once a product is bottled, everyone thinks that unbottled is ugly and unhealthy. Poor Mevlut!

Q. That’s curious, because the 70s was also the decade of cinema in Istanbul.

A. Yes, but what was damaging for Turkish boza vendors was not cinema but television. Once television was popular, and apartments got higher, boza sellers could not reach the upper floors.

Q. And what sense is there in looking for Mevlut today?

A. If you are asking me if I am nostalgic, I would say no. I am a chronicler, a historian. Would a historian or a chronicler feel nostalgic? In the end, the past is something I use to understand humanity, my characters, everyone that is placed in a social surrounding. The past is that fabric, that texture. Turkey is full of Mevluts, we’re all Mevluts. In my naiveness I am also a Mevlut, so in that sense he is a character that contains all. Essentially he is very well-meaning but he also makes silly mistakes that he regrets. The difference between Mevlut’s fate and Turkey’s fate is that Turkey got richer but Mevlut can’t. That’s why at the end of the novel his relatives pity him, realizing that this is related to his principles, his strangeness, his dedication to something deeper. That’s why even his nasty relatives feel respect toward him in the end.

Q. Is it right to consider this a political novel?

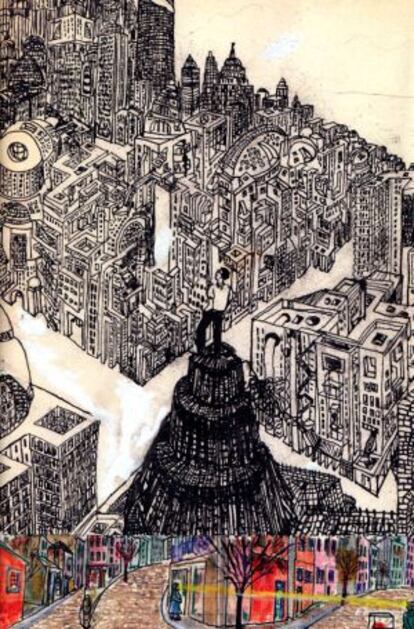

A. It is political in as much as Turkey is a very political country. And the streets are very political. But it is not deliberately political. But the more I wrote it the more it got political. It is political also in the sense that it teaches you the essential roots of political Islam. Why does he go to the Efendi? Because he is lost in modernity, because no one is listening to him, because he is lost in the chaos of Istanbul’s urban development. It is also political in the sense that it chronicles the military coups, the rise of the political Islam, Kurdish-Turkish fights and of course the construction frenzy, real estate development, the rise of high rises in Istanbul – they changed the skyline of the city. In that respect I feel very close to Mevlut. At the end of the novel he feels that he doesn’t belong to the city any more, although he is embedded in Istanbul so much.

Q. You represent fundamentalism in the novel, the ways of the Islamic faith, mosques, capitalism and the relationship between capitalism and the church and the church and political fundamentalism. That is a very subtle vein in the novel.

A. The success and establishment of a shanty town, a little development that comes out of nothing, culminates when these people finally get organized and build their mosque and their minarets, a symbol that is saying to the bourgeois establishment that we poor people came from rural Anatolia but we have our mosque.

Q. There is a symbol in the novel – the dogs that bark at Mevlut.

A. Oh, yes. Istanbul is famous for its packs of street dogs. I wrote about that in My Name is Red. I wrote about that in my autobiographical Istanbul book. And beginning from the mid-19th century, from Flaubert to Gérard de Nerval, all the visitors to Istanbul pay attention to its packs of dogs. In the mornings they hide in the cemeteries or they sleep, as you also saw here in the streets, but at night they organize and attack and behave aggressively. Many times Ottoman rulers, bureaucrats, sultans wanted to exterminate them, put them on an island and try to kill all the dogs, but people from Istanbul love their dogs, and it’s also an east-west symbol. Pro-western rulers want to exterminate dogs, while the people of Istanbul always want to protect their dogs. It was Gérard de Nerval who said in a very clear way that dogs are so important here because at night they eat the trash and they serve a function in the municipality.

Q. I see the book not only as a book about love, or the building of love, or even the sentimental education of a person who always remains unchanged, but about good luck and bad luck.

A. Bad luck becomes bad when you treat it as bad. The magic of Mevlut is his eternal optimism. As I told you he is more optimistic than me. Even if there is bad luck he has an extreme source of positive energy. Unfortunately, he is unlucky in a way. But on the other hand, he knows how to walk around it.

Q. Even with love he is unlucky in a way, but at some point he feels very happy about the outcome of his love story. It’s contradictory because he is always suffering because of love but he finds love in the end.

A. The good thing about Mevlut is that he does not complain about his bad luck. When bad luck is happening to him, he does not dramatize. Maybe it is not luck, good or bad things, but how we face them. That is as important as luck itself.

Q. You write about something that is also very relevant to Spain – the way that corruption is related to politics in Turkey. And the way in which Mevlut gets away from that. I think your tone, or the tone of the narrator, is very critical. Is this because corruption is very prevalent in Turkey?

A. Corruption in business and politics is a regular thing we are all used to. Especially in the last 10 years, in municipalities and the construction business. There is immense corruption. For example, a neighborhood like the one I describe in the novel, on the outskirts of Istanbul, or even at the center, where the regulations say you can only build four or five stories – the height of the building should not exceed that limit. Then suddenly they change it to seven floors and when this decision is made, if you’re close to the ruling party, you benefit from this. And unfortunately we live in a culture of immense bribery and corruption. This is in the story too, and for a Turk it’s not that dramatic, it’s a normal thing… One part of a normal Turk’s education is to learn how to give bribes. Even if you don’t want to learn it, they will teach you.

Q. Mevlut says that someone who is honest cannot tell lies to be rich. And there is a part of the book where you or the narrator ironizes about patriotism. For instance, Mevlut learnt when he was in secondary school that the best thing in the world is being a Turk. And being a Turk is a much better feeling than being poor.

A. Yes, the book is full of ironies like that. Mevlut is surrounded by right-wing friends and left-wing friends and he learns something from both sides. From left-wing friends he learns that he is a working-class proletarian and he doesn’t like it; from right-wing friends, he learns to love the Turkish flag, and the importance of being an honorable nation – he likes that better than being a poor person.

Q. Has Istanbul got better now?

A. It’s difficult to answer that question. We’re here on this island and around 60 years ago there was not a single building on the continental Asian side that I now see. How do I have the moral right to say that these 15 million people, each of whom in their own way is a Mevlut, shouldn’t have come here so that they can have a better, more classy life? In a way, history is so strong, demography, inevitable movements of peoples, is so substantial that saying things like “Things were better before” does not make sense. My duty is, and that’s how I felt when I wrote about Mevlut, is I feel like a historian, but a historian who pays attention to little details of the lives of people.

Q. I ask you that question because people who love Istanbul come from outside Istanbul. One of these people, a central character in the novel, Samiha, says at one point: “Istanbul has no end.”

A. This is the feeling I have now. Let me tell you this. When I was born here the city had a million inhabitants. Now they say it’s 16, 17 million. I have lived here 63 years. The change in the last 10 years has been bigger than the change in the first 53 years. In the first 53 years, say until the year 2000, the city remained more or less the same. Now it has got out of control. Even understanding what is happening requires a lot of work. So when Samiha says Istanbul has no end she means it. It sometimes takes three or four hours to get from one end of the city to the other.

Q. I think that love and time are the subjects of this book. Were you conscious of that or am I mistaken?

A. In the sense that love in this book is developed through time. Shall I tell the story? Because he actually does not get the beloved he wants. He marries another girl, which is at the beginning of the book so we can reveal that detail. But the time they spend paying attention to each other, fighting to survive, earn a living, raise children, that time they spend together is more important than their ideas about love. Mevlut writes these letters to someone else but at the end of the novel that doesn’t count, what counts is the time you spent with your loved ones. The book idealizes not romantic love but the love of sharing, fighting together, raising children together. Spending time together is more important than the idea of romantic love. Once he gets older it’s not these fancy romantic things that matter; what matters is that they are friends, that they are gentle to each other, that they care about their details, their smell, their legs, their arms, the way they talk, their little fights, that they are friends, that they share a life together, that they are nice to each other – even their fights are tender in a way. In the end what counts is the years they spend together, rather than – wow – I was in love with this person! In that sense I am proud that my book is very realistic and romantic. But it is not the old-fashioned romanticism of seeing a picture of someone and you fall in love. I am doing that but the novel is also implying that the beautiful thing about Mevlut’s love with his wife is that it is very down to earth, very realistic, it’s about collaboration, fighting through life together, sharing things, and what makes them do this is their poverty and their modest acceptance of the hardships they come across. Their success lies in the fact that they closely collaborate and they accept hardships in a modest way. They are not ambitious like upper-class bourgeoisie, but they aim for the small happinesses that life gives them. Not that I am praising these small happinesses but what the novel does is chronicle the way realistic love works. They need to love each other in order to survive.

Q. But there is a sentence, I don’t remember who says it, but it’s very interesting on that aspect of the novel, about love. What maintains love is the fact that it is impossible. Love is impossible.

A. Well, first of all, love is a huge ideology. All pop songs, traditional literature, romantic literature, poetry, music… we’re surrounded by it. But on the other hand I want to underline that all cultures, civilizations and countries live that love in very similar ways, but from country to country, civilization to civilization, it’s different. For here, this is the love of a poor person coming from a conservative peasant background. Here love would be restricted to the context of marriage, to the context of the lovers’ struggle to survive. But it is not a romantic idea. Mevlut writes love letters because there’s no one to write to. Don’t forget that at the heart of this story, too, is the love story in a culture where woman and man, boys and girls, don’t get together easily. My characters meet each other at someone else’s wedding and this is the typical place where you meet your would-be husband in Turkey.

Q. Do you agree with Mevlut’s leftist friend, Ferhad, that Mevlut’s frankness and ingenuity are valuable not only for the company, but for the whole world?

A. Yes, Ferhad says this to Mevlut to persuade him to join his company, because I think everyone, all the readers of this book would agree that Mevlut in the end is a good guy. Ferhad knows that he is a good guy. Not that he may not cheat him. But even if he does cheat him, he would do it in a minor way. My novel is suggesting perhaps horrors of Turkish history, streets, traffic, politics, pollution, destruction of the past, political and cultural horrors, the rise of political Islam and all the bad things, Kurdish-Turkish nationalism, clashes, killings, bombings – all this can be tolerable if we see it through the eyes of a good person. As Ferhad needs a good guy like Mevlut to collect electric bills, I need him to tell my horrible story. Mevlut’s sweetness is an antidote to the horrible realism of Turkey. I also want to add that I’ve been writing novels here in Turkey for the last 40 years and up to now Mevlut has been my most popular character. Turkish readers liked him. Partly because he is not an arrogant upper-class person like Kemal, but also because he is living the life of a regular, normal, everyman Turk. But compared to an everyman he has more goodness. But it’s intertwined with this strangeness in his mind, his individualism, his eccentricity in his spirit – these are the things that make him a character.

Q. And does Ferhad’s reflection make this novel a moral lecture on what is going on in the world today?

A. Yes, of course. If the world were full of Mevluts, life would be easier for all of us. But if life was full of Mevluts, maybe we wouldn’t have all these high rises around and a lot of people unfortunately want high-rise buildings, want technological development, want to accumulate money, want the banks, want the big factories, want the big armies.

Q. But Mevlut says no to Ferhad because he thinks that he can’t confront those corrupted bosses. He prefers to go to the little houses, to the poor neighborhood.

A. Because poor is easy to deal with. Corruption is scary. Ferhad is in trouble because of big corruption money. There is a lot of corruption in this book, but the tone I adopt to talk about it is not a moralizing one – I don’t point the finger at anyone. I limit myself to giving a gentle smile.

Q. Is this book in any way about finding happiness?

A. Yes. Although I still consider myself a post-modern writer, I have also subscribed to and honored the idea of the 19th-century novel – the novel of Tolstoy, Stendhal, Balzac, where the main question is: what is life? Meaning more than just what is the experience of life, this question is about what should be in our mental hierarchy? Is it happiness or is it fame and success as in the Renaissance? Is it friendship and family or adventure and romantic escape? These are the dilemmas. There are many eternal dilemmas like these. Is it belonging to the same house, same village, same street, or is it change? Is it to carry on with many women and be a Casanova, or is it a more relaxed life? Does social life matter more than introspection and marking out our uniqueness? These are the values: family, friendship, happiness. And the great thing about 19th-century novels is that Tolstoy and Stendhal always address these questions and try to understand and revisit the hierarchy of values. In that sense the right question is: what is the important thing in life? Happiness, maybe, the most reasonable thing. And then what is happiness made of? What makes one happy? Is it money? Is it success? Is it your image seen through others’ points of view? Is it money? Is it political liberation? Or is it personal happiness in a closed house, so to speak? This novel in that sense is very much a 19th-century novel looking at this, and the 19th-century novel always looked at these problems through the prism of family, marriage and friendship. Our task is combining this with the individual and the unique character. And in that I behave like a 19th-century novelist.

Q. And all those novels you mention look for happiness through drama.

A. Yes. I try to express and find happiness through drama.

Q. And you yourself know what happiness is now?

A. A good question. Perhaps happiness is something that comes with time. At my age, I think happiness is about not worrying too much. But I’m an ambitious person. I have so many self-imposed worries! Is the translation of this book good in English? It’s too much worrying at my age perhaps. But I’m like that. And although now my books are translated into 62 languages, don’t forget that I am also a provincial guy like Mevlut! The problem with fiction about the life of the poor is that after three sentences, it becomes very sentimental and melodramatic. My intellectual challenge was to write about poor or dispossessed people, but in a very realistic and unsentimental way.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.