Guerrilla who kidnapped Real Madrid star Di Stéfano dies in Venezuela

Paúl del Río held soccer player for two days in 1963 to call attention to armed insurgency

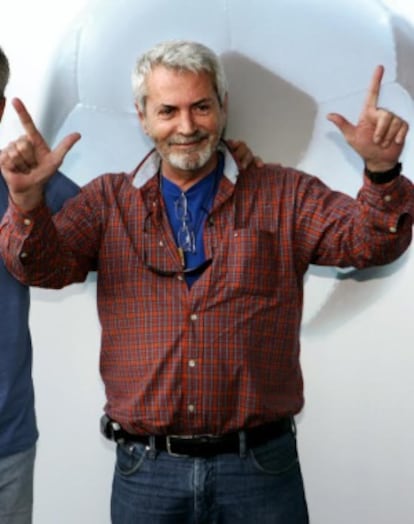

Paúl del Río, a former leftist guerrilla leader who was widely known for organizing the 1963 kidnapping of Real Madrid soccer star Alfredo Di Stéfano in Caracas, died Sunday in the Venezuelan capital. He was 72.

The son of Spanish Republicans in exile, Del Río was born in Cuba but migrated to Venezuela with his parents in 1945.

As a youth in the 1960s, he joined the budding guerrilla movements then being organized and later formed the roots of what became the Venezuelan Communist Party (PCV) and the Leftist Revolutionary Movement (MIR).

The son of Spanish Republicans in exile, Del Río was born in Cuba but moved to Venezuela in 1945

The two groups – which years later would become legitimate political parties – were backed by Fidel Castro and aimed at overthrowing the young democracy that had sprouted in 1958 after the fall of dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez.

Known by his nom de guerre Máximo Canales, Del Río became the leader of an MIR commando unit that performed daring operations that caught the public imagination, including the 1963 seajacking of the Venezuelan cargo ship Anzoátegui while en route to Brazil, and the 1964 kidnapping of Michael Smolen, the then-military attaché at the US Embassy.

However, Del Río’s most famous operation was perhaps not his boldest. In August 1963, Real Madrid was scheduled to play a summer match in Caracas. Di Stéfano, nicknamed the Blond Arrow and considered the best soccer player in the world at the time, was staying at a hotel when Del Río and another person passed themselves off as police officers and captured the Argentinean-born star.

Di Stéfano was held for 70 hours and only freed when his kidnappers won their main objective – to let the world know about the armed insurgency that existed in Venezuela. Di Stéfano died last July in Madrid at the age of 88.

For the rest of his life, Del Río recalled the kidnapping. In 2005, he attended the Caracas premiere of Borja Manso’s documentary Real: The Movie.

Del Río ended up in prison in 1971 and spent the next three years in custody until the Venezuelan government declared a general amnesty for all rebels if they gave up the armed struggle and joined the political arena.

Following his release, Del Río returned to his career as an artist.

After President Hugo Chávez was elected in 1998, he became the Bolivarian Revolution’s preferred, if not official, artist.

One of his sculptures can be found in the lobby of Petroléos de Venezuela (Pdvsa) in Caracas. It was dedicated to the “recovery” of the state-owned oil company in December 2002 just a few years after a previous administration had opened its doors to private investment.

Chávez asked Del Río to design the stone tomb where South American liberator Simón Bolívar was laid to rest in 2011 after the government had exhumed his remains from the National Pantheon for a forensic study.

Nevertheless, even under the Chávez presidency, Del Río was never able to escape controversy. In 2008, he and another group of former guerrillas took over San Carlos Prison, an old colonial fort in Caracas where political and military inmates were held during the 20th century.

Del Río and the other former insurgents were protesting the manner in which a remodeling plan of the historical structure was being undertaken. He spent part of his prison term in the 1970s at San Carlos, just as Chávez did when he was imprisoned following his attempted coup on February 2, 1992.

His action resulted in some success. From then on, Del Río set up a foundation for ex-political prisoners at San Carlos and served as an unofficial administrator at the site.

It was at this ancient fort – the same place where he was incarcerated – that he reportedly decided to take his own life on Sunday with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his heart.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.