The Spanish comeback of the point-and-click adventure

Four Madrid studios have joined the growing global trend for the 1980s video game genre

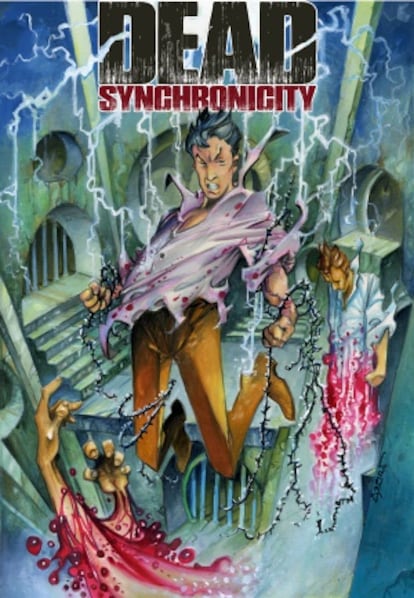

Traveling through time using a record player needle, facing an apocalyptic future in which humans are liquefied into blood, or becoming a boy from the Makoa tribe are three of the setups for new video games bringing an old genre back from the dead.

Four Madrid-made titles are now joining a new global trend for classic point-and-click graphic adventures.

The 1980s was the decade of nostalgia and wonderment, of E.T. and Michael Jackson, and of Star Wars creator George Lucas’s incursion into video games with a company named LucasArts.

The idea was very simple: to tell bizarre stories using good old-fashioned words. You used a menu to choose available actions, an inventory to store objects, and your mouse to discover stories that pitted pirates against insults (Monkey Island), unveiled alien conspiracies (Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders) and sent the most famous archeologist of all time to the bottom of the ocean (Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis).

Smartphones and tablets seem made for graphic adventures” Luis Olivan, co-creator of Dead synchronicity

Their star waned as the new century dawned, going silent for an entire decade. But now point-and-click adventures are back and stronger than ever.

“I think it’s due to several factors,” says Luis Olivan, one of three siblings who created Dead synchronicity, an adventure in which humanity dissolves into a pool of blood. “On one hand there’s the technology. Smartphones and tablets seem made for graphic adventures. Also, those of us who grew up with these adventures are now in a position to create them ourselves. And then there is the rise of indie trends in videogaming, which means that niche genres can find very large niches.”

Large enough, in fact, to raise over €3 million on crowdfunding site Kickstarter, which is what Monkey Island co-creator Tim Schafer did to fund his new graphic adventure, Broken Age.

Not that the Olivan brothers did too bad themselves: they raised over €40,000 through their own crowdfunding effort on the site.

The siblings had two ways to go: stick to the past or break the rules. Their choice was to respect the nostalgia of the games that thrilled them as kids. But there are others, like Edu Verzinsky, who are willing to take the plunge.

Born in Madrid in 1990, Verzinsky’s idea is to make a game in which you change history by traveling through time using ... a record player.

“The idea is, where do I think humans are headed? Imagine a civilization that could use the speed of light,” he explains. “You could plant a seed, and in a matter of minutes to you, you would have an entire forest. So there’s this company doing social research, traveling through time and experimenting by tinkering with things.”

These future humans, who are synthetic, blue, and really rather ugly, use vinyl and needles as a map on which time is not measured in seconds but in musical notes. Each groove is a possibility to kill Hitler before he was even born or to make him win World War II. The plot has earned Verzinsky a contract from an independent US publisher.

These new creators are making do without the dialogue and text that earlier graphic adventures relied on. In Missing translation, there is an entire new language based on geometry that players have learn intuitively.

“There is no tutorial, no text of any kind. It’s about solving the puzzles through an indirect narrative,” explains Luis Díaz Peralta, a twentysomething who has already earned several international awards for his game and a deal with Steam, the Amazon of video games, which will sell his creation.

Carlos Hernando also chose to tinker with the formula in A rite from the stars. His main character is a child from a tribe with magic powers. “The characters in graphic adventures were always regular people. That is why, given that I love fantasy books, I wanted to add some extra powers to things. This does not mean that I don’t like continuity – it takes all kinds,” he explains. “But in our studio, people were not diehard fans of games from the past, so innovating was not a problem for them.”

Getting contracts from US firms or raising money through crowdfunding is a source of pride for all of these Spanish creators, yet there is still a big thorn in their collective side: the only way to succeed is by looking abroad and creating stories in English.

This year, for the first time, the Spanish government has offered grants to videogame creators, but over €800,000 of the total €2 million available went to one company, Mercury Steam, which specializes in multimillion-euro megaproductions.

“The problem is that it [the money] was basically aimed at people with no actual need for money, especially not from public coffers,” says Verzinsky.

Hernando agrees emphatically: “There are around 300 companies in Spain, and I can’t say that I know them all, but I do know 50 or 60 of them from trade fairs, and what you see everywhere is precarious working conditions. And what the government did is give the money away mostly to companies that already have money. And that doesn’t exactly help build the business fabric. This is an industry that brings in a lot of money, so every country should be interested in keeping it strong.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.