Ballet diplomacy

Dancers and choreographers have been persecuted and ostracized under the Castro regime

The scene that opened the gate for renewed diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba last week had its first official rehearsal in the ballet world four years ago. It was also an almost exact imitation of that innocent ping-pong game used as the preamble to a reset of Sino-American relations back in the 1970s. At the time, the Cold War was at its lowest temperature and the American table tennis team’s visit to the People's Republic of China set the stage for the arrival of Henry Kissinger. The rest is history. Now ballet shoes and tutus have replaced bats and balls, while John Kerry may become the first US official to travel to Cuba.

The ballet world has sidestepped much of the embargo. Many American dancers traveled to Havana on their own: particularly notable was the visit of Cynthia Gregory and Ted Kivitt, the principals at the American Ballet Theatre (ABT) in New York in the mid-1970s. Around the same time, the prima ballerina at the Cuban National Ballet, Alicia Alonso, overcame bureaucratic hurdles and found her way to the Metropolitan in New York. Jane Hermann, ABT’s director and a woman with many connections in Washington, facilitated the trip.

The ballet world sidestepped much of the embargo. Many US dancers traveled to Havana on their own

But what happened four years ago at the International Ballet Festival of Havana was different. For the first time, ABT and about 30 or so of its artists, made an official trip to Cuba. Among the group was its principal female dancer, Xiomara Reyes, a Cuban immigrant. Besides Alonso, Reyes is the only other Cuban to have reached that level within what may be considered the top ballet company in the US. The United States does not have a national company and ABT, which receives generous subsidies from the National Endowment of the Arts, serves the function that a national organization would have.

There was a lot of back and forth involved in planning the trip, with long meetings in Washington. And it required explicit authorization from then brand-new Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

In the end, the rehearsal was satisfactory. Within that tight, peculiar, but glamorous ballet world, officials were able to accomplish what has now become an important feat in world history. What started with ballet has become an unfurled carpet – no one can say whether it is red or blue – for Hillary Clinton or whoever else moves into the Oval Office after Obama. These events are as significant as they are paradoxical when you take into account the moral trials and immigration hurdles many Cuban dancers have gone through.

The largest emigration of ballet dancers after the one that followed the 1917 Russian Revolution – which continued unabated right through the Stalin years and up until the fall of the Berlin Wall – is the flight of Cuban ballet dancers who sought freedom and better professional prospects.

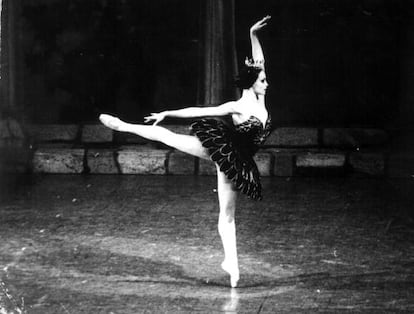

Today Cuban dancers work all over the world. Hundreds of them fled from airports, escaped by hiding in the trunks of cars, or jumped out of hotel windows. Some built prosperous careers while others faded away. Their stories are unlike those of any other artist, without taking away the merits of writers, poets, painters and musicians. Over its almost six decades in power, the Castro regime made its ruthlessness obvious in many cases, including its penchant for vengeance. One of the most notorious cases was that of principal dancer Rosario Suárez, the top performer of her generation and certainly the most famous Cuban dancer after Alicia Alonso. Suárez fled while on tour in Madrid, but Spain, under pressure from Havana, denied her political asylum. These stories have yet to be written.

The truth is, there are too many deaths, too much pain, too big a stain in the swelling waters of the Straits of Florida where countless Cuban lives were swallowed up as they reached for, not the consumer world, but freedom itself. A spy swap and a few scenes of a ballet performance cannot wipe the slate clean. It isn’t fair.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.