Shedding light on Spanish Schindlers

Madrid exhibition reveals how 18 diplomats helped Jews escape the Nazi death camps

A new exhibition in Madrid sheds further light on the role played by Spanish diplomats in saving the lives of at least 8,000 Jews in German-occupied Europe during World War II.

Now on display at the Spanish Foreign Ministry’s Santa Cruz palace, Más allá del deber (or, Beyond the call of duty) is the result of two years’ research by historian José Antonio Lisbona, who was given unprecedented access to official files at the direct request of Foreign Minister José Manuel García-Margallo. It details the work of 18 diplomats, including Ángel Sanz Briz, the Spanish chargé d’affaires to Hungary during the final years of World War II who helped many Jews avoid being deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in mid-1944 after Germany invaded Hungary. In just two months that year, the Germans sent around 424,000 Hungarian Jews to be gassed in the death camp.

The files, which Lisbona was forbidden to share with journalists or other researchers, dispel once and for all the idea that General Francisco Franco played a role in saving Jews from German hands in eastern Europe, although several thousand French Jews were permitted to cross Spain in small groups en route to the United States and Palestine following the German invasion of France in 1940.

The files dispel once and for all the idea that Franco played a role in saving Jews in eastern Europe

“During the years when the Franco regime was isolated internationally, there was an attempt to spread the myth that Franco had directed the operations to save the Jews, when in fact the very opposite was true,” he says. “These diplomats acted beyond their duty, putting their careers and their lives at risk.” In many cases, says Lisbona, not even close family members were aware of what they had done, citing the case of former justice minister Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, who opened the exhibition last week and had not known the role his grandfather played in helping Jews escape deportation in Romania – although that of his great-grandfather, José Rojas y Moreno, was known.

“Their example should be an inspiration, particularly at times like these, when society is looking for moral guidance,” said Margallo at the opening. Also present at the inauguration was Ana María Canthal, whose father, Fernando Canthal, was the Spanish consul in Milan between 1943 and 1945, and used his close contacts with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini to help Jews escape following the German occupation of Italy in late 1943. “It was a huge surprise for me, and I am very proud,” said one of Canthal’s grandchildren who attended the ceremony.

“Eighteen heroes”

This is the list of the 18 Spanish diplomats who helped Jews escape from German-occupied Europe in World War II:

Ángel Sanz Briz, chargé d'affaires in Budapest betwen 1942 and 1944.

Miguel Ángel de Muguiro, who worked in the Budapest embassy between 1938 and 1944.

Sebastián Romero Radigales, consul general in Athens between 1943 and 1945.

Father Ireneo Typaldos, in Athens between 1942 and 1944.

José Rojas y Moreno. In Bucharest between 1940 and 1943.

Manuel Gómez-Barzanallana. In Bucharest between 1943 and 1945.

Julio Palencia Álvarez-Tubau. In Sofia between 1940 and 1943.

Eduardo Gasset y Díez de Ulzurrun. Consul and chargé d'affaires in Athens and Sofia between 1941 and 1944.

Bernardo Rolland y de Miota. Consul general in Paris between 1939 and 1943.

Alfonso Fiscowich y Gullón. Consul general in Paris between 1943 and 1944.

Eduardo Propper y de Callejón. First secretary in Bordeaux in 1940.

Alejandro Pons y Bofill. Honorary vice consul in Nice between 1939 and 1944.

José Luis Santaella. Agricultural attaché in Berlin between 1942 and 1944.

Antonio Zuloaga Dethomas. Press attaché in Paris, Vichy and Algiers between 1939 and 1944.

Luis Martínez Merello y del Pozo. Consul general in Milan between 1937 and 1942.

Fernando Canthal y Girón. Consul general in Milan between 1943 and 1945.

Jorge (Giorgio) Perlasca. Posed as consul in Budapest after Ángel Sanz Briz was recalled to Madrid in November 1944 until the arrival of the Russians in January 1945.

Santos Montero Sánchez. Posed as a consul. Saint Étienne, 1942-1944.

Eduardo Gasset, a nephew of Spanish writer and thinker José Ortega y Gasset, was the consul and chargé d’affaires at the Spanish embassies in Greece and Bulgaria between 1941 and 1944, and used his influence to help prevent the deportation of Sephardic Jews from the Greek city of Salonika. The term Sephardic comes from Sefarad, the old Hebrew name for Spain, and applies to those who could trace their origins to before the expulsion of the country’s Jews in 1492.

“In this country during the Franco era, if you did something good, you were shot, exiled, or forgotten. My father has been forgotten. What these diplomats did was to show that Spaniards, as well as being Cainites, also had something of Quixote in them,” said Gasset’s son José María Gasset at the opening.

Some Spanish diplomats paid for their heroism by losing their jobs: Gasset’s colleague at the Spanish embassy in Sofia, Bulgaria, Julio Palencia, was expelled from the country after adopting the two children of a Sephardic Jew, León Arié, who had been murdered by the Germans.

Antonio Zuloaga, the son of the Spanish painter, and the Spanish press attaché in Paris, Vichy and Algiers, helped René Mayer, the man who would be France’s first post-war prime minister, escape.

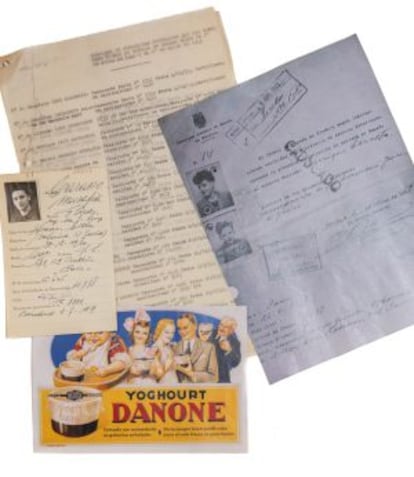

“But it was a desperate struggle, and often a futile one,” says Lisbona, recounting the case of Bernardo Rolland, the Spanish consul in Paris during the German occupation. He managed to save Daniel Carasso, the owner of yogurt maker Danone, but not his sister Flora, who after marrying a Greek Jew lost her Spanish nationality. She died in the gas chambers.

Addressing the audience at the inauguration – which included the Israeli ambassador, Alon Bar; the president of the Federation of Jewish communities of Spain, Isaac Querub; and the honorary president of the International Alliance for the Memory of the Holocaust, Yehuda Bauer – the Spanish foreign minister said: “Ideologies of hate are coming back, and anti-Semitism is one of these ideologies. No society, including our own, is safe from its effects, and that is why we must always be on our guard.” Margallo took advantage of the event to say that when Spain takes up its temporary seat on the UN Security Council in January 2015, it would “make every effort” to reach a just and lasting peace based on the recognition of two states: Israel and Palestine.

Más allá del deber. Until December 19 at Palacio de Santa Cruz, Plaza de la Provincia, Madrid. www.exteriores.gob.es

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.