From Guantánamo to Delaney Hall: Trump administration increases detention capacity to speed up deportations

The reopening of some of the largest detention facilities and the adaptation of military bases to house migrants are aimed at fulfilling the Republican’s major campaign promise

The plan to send migrants to Guantánamo Bay made headlines, but other moves are also being made in U.S. immigration policy to address the operational challenge of detaining tens of thousands of people necessary for Donald Trump’s biggest campaign promise: the largest deportation in history.

The Trump administration has announced in the last week the reopening of some of the largest migrant detention centers in the country, from Texas to New Jersey, while plans have also been reported to adapt and expand several military bases in strategic places in the country to house people awaiting deportation.

While Trump has yet to exceed the monthly deportation rates of his predecessor, Joe Biden, the increase in available beds for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) signals the beginning of a new phase in his mass deportation strategy.

Just two weeks into his second term, Trump and his immigration team — led by border czar Tom Homan and senior White House adviser Stephen Miller — were confronted with a major obstacle that delayed their plans to expel millions of undocumented migrants: ICE simply didn’t have enough space to detain such a large number of people in deportation proceedings. By early February, hundreds were being released as immigration detention centers — described as inhumane by migrant advocacy groups — were operating at 109% capacity. Nearly 42,000 detainees were housed in facilities with just 38,500 available beds.

The highly publicized immigration raids faced issues from the outset, and the ongoing confrontation with sanctuary city jurisdictions is likely to continue to be an obstacle to arresting migrants at the desired scale. Additionally, negotiations with countries of origin to take back their citizens have proven difficult, as evidenced by the tensions between Colombian President Gustavo Petro and Trump, or the controversial “solution” of sending migrants to Panama for repatriation.

What’s more, the lack of space to house detainees during the lengthy deportation process — weeks, months, or even years due to the backlog of over 3.5 million cases in immigration courts — is creating a bottleneck that is completely stifling the administration’s ambitious plans.

The latest moves are clearly aimed at addressing this challenge. Last Wednesday, CoreCivic, a company that operates private prisons across the country, announced it would reopen a controversial immigrant family detention center in Dilley, Texas, located between San Antonio and the border city of Laredo. This decision came after the company reached a new agreement with ICE. According to CoreCivic, the facility will house up to 2,400 people, despite being closed last year by the Biden administration following a decade of operations marked by controversy over mistreatment and family separations. In addition, the company revealed plans to expand immigrant capacity at four of its regular prisons in Mississippi, Nevada, Ohio, and Oklahoma, to accommodate an additional 1,036 people.

Similarly, just days earlier, ICE announced the reopening of the largest immigration detention center on the East Coast, located in Newark, New Jersey. The Delaney Hall facility, owned by the private prison company GEO, has a capacity of 1,000 beds and ceased operating as a detention center in 2017. However, its proximity to Manhattan and Newark International Airport makes it a strategically valuable location. “[It] streamlines logistics, and helps facilitate the timely processing of individuals in our custody as we pursue President Trump’s mandate to arrest, detain and remove illegal aliens from our communities,” said Acting ICE Director Caleb Vitello in a statement.

The announcement sparked concern among Trump’s critics in New Jersey, as it came alongside the signing of a $1 billion contract with GEO. “This 15-year, $1 billion contract, announced the very same day that GEO Group released its fourth-quarter earnings, is not about making New Jerseyans safer or fixing our broken immigration system,” said Democratic Senator Cory Booker. “Instead, it demonstrates this administration’s driving motive to enrich its favored corporations while wasting taxpayer dollars.”

The company, for its part, does not hide the fact that it considers the contract a great opportunity. “We are continuing to prepare for what we believe is an unprecedented opportunity to help the federal government meet its expanded immigration enforcement priorities,” said George C. Zoley, the CEO of GEO.

But the Trump administration’s boldest gamble appears to be the use of military bases to detain immigrants facing deportation. After announcing the use of a prison near the Guantánamo naval base in Cuba to house up to 30,000 migrants, authorities sent a small group of detainees to the island in early February. But legal and operational obstacles have temporarily derailed that plan. By late February, ICE reported that the facility had been emptied of migrants. A Congressional delegation visited the base last Friday to assess whether conditions were acceptable for detaining migrants. For now, it remains unclear whether the controversial Caribbean facility will be reconsidered as a mass detention site for migrants.

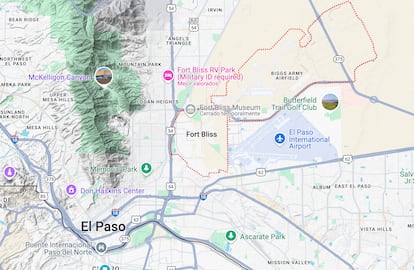

What is known is that another military base, Fort Bliss in El Paso, has become a central focus of the deportation plans. According to internal communications obtained by NPR, the plan is for Fort Bliss — whose airbase has already been used for deportation flights — to eventually house up to 10,000 immigrants. For now, the plan is to house 1,000 detainees at the base during a 60-day trial period before it officially becomes the “central hub for deportation operations.”

Whether Fort Bliss’s use as a detention center proves successful or not, it could serve as a model for as many as 10 other military bases across the country, including Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey, Niagara Falls Air Reserve Station near Buffalo, New York, Hill Air Force Base in Utah, and Homestead Air Reserve Base near Miami.

The exact capacity of these military bases remains unclear, as temporary camps could be constructed on base land to increase space. There are also concerns about the cost of these measures and their potential impact on other areas of the budget, as detaining migrants is by far the most expensive aspect of the deportation process.

However, the administration, which has been cutting what it deems inefficiencies — including laying off thousands of federal workers — does not appear to be reducing spending on this initiative. By declaring a national emergency over the immigration situation, Trump can leverage military funds and resources for these operations, and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth previously said that “any necessary assets” are available for this goal.

There are also concerns about potential mistreatment of detainees, based on past cases. For example, at Fort Bliss, an internal watchdog from the Department of Health and Human Services found that children and adolescents experienced anxiety and panic attacks due to inadequate resources and insufficient training of officials. Similarly, Guantánamo has become synonymous with abuse, following numerous serious and disturbing reports of detainee mistreatment.

There is no clear timeline for the mass deportation effort to reach full speed, and the obstacles ahead are considerable. Yet the push to expand ICE’s detention capacity signals that the direction of this initiative remains unchanged. A few weeks ago, Miller made this clear: “We are shortly on the verge of achieving a pace and speed of deportations this country has never before seen.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.