The silent history of Spanish illiteracy

More than 730,000 people in Spain can’t read or write, most of them older women, migrants or Roma

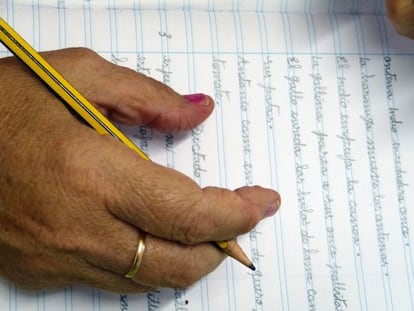

They are learning to write the word “historia” (history). The teacher asks how to spell it, and the students, some of whom are 68 years old, try their luck: “With an I?” “With a Y?” “In capital letters?”

Seconds later, the mystery is revealed. The word begins with a silent H – the silence of absence, the silence of a history of illiteracy that endures into the 21st century.

September 8 was International Literacy Day, and a reminder that there are still 730,000 illiterate people in Spain, of whom 67 percent are women, according to 2011 figures from the National Statistics Institute.

They survive by asking questions of everyone around them, trusting they will be told the truth. They ask about the type of milk they are buying, the name of the street they are on, which bus they need to take, and how to dial a phone number. They have no driver’s license, cannot read maps, know nothing about what’s in the contracts they are signing, do not use computers or the internet, and have never read a book.

And they all agree they share a sense of shame.

“I used to ask the woman down at the bank to read me the documents that I had to sign. I pretended to have left my reading glasses at home. But of course it wasn’t true,” says Dolores Fernández, 68.

Now, Dolores proudly shows off her notes with the word “historia” spelled right. She has been taking classes courtesy of an association called Los Vencedores, located in Seville’s Martínez Montañés neighborhood, in the Tres Mil Viviendas area, where illiteracy rates are as high as 50 percent. The European Union has declared this place a preferential action area because of its high degree of social exclusion.

“I was never able to study because I started working as a child and after that I got married and raised my children. Now I can express myself better,” explains Dolores.

Of Spain’s 490,000 illiterate women, 57 percent are between 65 and 84 years of age.

“The average illiterate person in Spain is the product of two trends. One is residual, and affects people over 65 who were forced into jobs at a very young age or had to care for relatives. The other one is linked to ethnic or immigrant minorities,” explains Antonio Aviño, an emeritus professor at Murcia University and author of La alfabetización en España: Un proceso cambiante en un mundo multiforme (or Literacy in Spain: a changing process in a multi-shaped world).

The promise of a driver’s license is motivating the Roma community to learn to read

Carmen Pérez, a cheerful 71-year-old, illustrates the first case. She started working as a house maid at the age of nine, retired at 66, and never learned to read. But now, as she finds herself making progress, she says she is starting to feel better.

Carmen is learning at the Polígono Sur Adult Continuing Education Center in Seville, which has just earned Unesco’s Confucius Prize for Literacy. “I can’t wait for the school year to begin again so I can go back to class. I study every day,” she confides enthusiastically.

Carmen is the result of historical inequalities that have continued to drag on over the years, says Professor Aviño. “Who is to blame for this? The answer is extremely complex, as we are talking about an issue that is over 200 years old. But we need to mention the lack of progress represented by the Franco regime, especially when it came to women. The schooling levels of 1970 could have been reached 20 years earlier, according to the Second Republic’s plans. We are still laboring under that, and some obvious results are on display in the low performance of Spanish students in the PISA report.”

“Sometimes it’s not just about learning to read and write,” adds Gabriel González, author of the Unicef report La infancia en España 2014 (or, Childhood in Spain 2014). “There are other elements that help you improve your condition in society, such as learning how to write a request to a government agency.”

His report points out that Spain has the highest school dropout rate in the entire European Union: 23.5 percent.

“Dropout rates are very much linked to the father or mother’s own education levels,” reads the report. “For instance, rates among youths whose mothers lack post-mandatory education is in excess of 30 percent, but it is barely 4.6 percent when the mothers have higher education.”

Magdalena Del Canto, 71, spent half of her life as a hospital cleaner, and neither of her two children went to university. But her granddaughter did, and now she is a teacher.

“She calls me every day to see if I need help with my homework,” says Magdalena, sitting at a desk inside the Polígono Sur center.

Andalusia, Extremadura, Castilla-La Mancha, the Canary Islands and Murcia have traditionally posted the highest illiteracy rates in Spain. Aviño’s research finds that learning has been slower among women in rural areas.

“The central government – both this one and the previous ones – has overlooked adult education and left it in the hands of regional authorities,” says Aviño. “There is nothing relevant on the issue in the education reforms of recent administrations.”

“Andalusia has been promoting adult education programs for the last 34 years. But it’s not enough, and the central government needs to do more,” says Ana García, director of the Polígono Sur center.

Teodora Trenado, 64, reads out a poem written by a fellow classmate. “Male participation in the program is noteworthy. It’s not easy for them to overcome their sense of shame,” notes Luis Ruiz, a teacher at the center.

Alberto García, a 40-year-old polisher, says he doesn’t need to read or write to do his job, and admits he has signed contracts without understanding what was on them. Now he shares a classroom with Carmen, Magdalena and Teodora: “Once you see people who are just like you, there’s no problem any more. You stand to win more than you stand to lose. People who cannot read are not going to get many jobs.”

After they get over their embarrassment, the next challenge is keeping their attention” Luis Ruiz, teacher

“After they get over their embarrassment, the next challenge is keeping their attention. They want to learn straight away,” explains Ruiz, adding that some of his students are here because they need their driver’s license. Until 2008 it was possible to take a special exam using videos, but there are no exceptions to the rule any more. “Beginner readers are granted more time, but an application needs to be filed with the provincial traffic authority,” he adds.

Remedios Gabarre, 39, is taking it easy after caring for her four siblings. She is one of the 60,000 women aged between 30 and 49 who never learned how to read. She is also part of the Roma community.

“I want to get my driver’s license and become a street vendor,” she says hopefully. Remedios adds that if she ever has children, they will all go to school.

Since 2008, driving without a license has been a crime punishable by imprisonment in Spain.

“This immediately created a need to learn how to read and write. It was more than enough reason to bring literacy to the Gypsy community,” says Beatriz Carrillo, president of Amuradi, an association of Roma women with college degrees.

“It’s one of the biggest demands by the Gypsy community. And the promise of a driver’s license motivates them to learn to read, as does the promise of being able to use social networking sites,” she adds.

This introduces the issue of digital literacy, which is very much present in developing countries. “Spanish society has gone from having a low literacy rate to embracing electronic communication channels,” adds Aviño, who forces his students to read printed books.

Carmen Pérez happily announces that she was recently able to read her granddaughters a story. But there are bigger challenges up ahead: her son has presented her with a copy of Don Quixote, and Carmen is convinced that as soon as she can read fluently, she will tackle the literary masterpiece. She is also planning to write the story of her life.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.