Newly unearthed documents shed fresh light on ‘Don Quixote’ author Cervantes

Finds in Seville reveal the celebrated writer worked as a purveyor for Philip II’s navy

An archivist in a small village in Seville province has discovered four documents that could shed new light on the life of Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote.

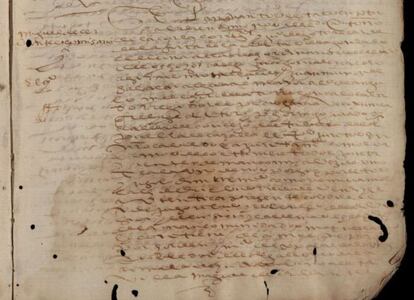

Three years ago, José Cabello was looking through the thousands of documents dating back to the mid-16th century stored at an archive in Morón de la Frontera relating to the village of La Puebla de Cazalla when he came across a manuscript dated March 5, 1593 in which Cervantes is identified as a supplies officer for Phillip II’s navy by order of Cristóbal de Barros, the supplier of the Indies fleet. The novelist’s task was to collect wheat and barley for the navy.

“The document is important because it proves that Cervantes was in La Puebla, which we didn’t know until now, and it establishes a relationship with De Barros, who built the vessels that fought in the Battle of Lepanto, as well as supplying the ships that sailed to the Indies,” says Cabello. Cervantes was severely wounded at the Battle of Lepanto, which took place in 1571 off the west coast of Greece and marked a major European victory over the Ottoman Empire. Four years later, returning to Spain from Italy, he was captured by Algerian pirates and kept as a slave for five years until a ransom was paid for his release. Cervantes is known to have spent from 1587 to 1597 in the province of Seville. He would publish the first part of Don Quixote in 1605.

The documents came to light after more than 12 years of painstaking detective work by Cabello, who went over microfilmed copies of the documents made in 2002.

I also found another document establishing that Cervantes authorized a woman called Magdalena Enríquez to claim his salary”

Cervantes’ relationship with De Barros led Cabello to the General Archive of the Indies in Seville, a vast repository of documents relating to Spain’s empire, where he found payment orders issued in November 1593 by De Barros to Cervantes for the sum of 19,200 maravedíes – “a very respectable amount for those days,” says Cabello – for his work as a “commissioner” for the royal tax office in several municipalities in Seville. “I also found another document establishing that Cervantes authorized a woman called Magdalena Enríquez to claim his salary. This is the first time we have come across her in relation to the author,” says Cabello, who is working on two articles about his finds.

But Francisco Rico, a specialist in Cervantes, plays down the significance of the discoveries, describing them as: “interesting, but we still don’t know much about the man, about his private life, his thoughts, or his relationships with the women in his family. The appearance of Magdalena Enríquez could be an interesting clue, but I wouldn’t get too excited, because she was a baker who worked for the fleet, and so the relationship could be purely commercial.” Rico says that there are many documents that detail Cervantes’ work as a supplies officer, but very few that give us insight into his personality: “That is something we must deduce from his work.”

Cabello, however, insists that the documents could open the door to new research into the life of the man who wrote the first great novel in Western literature. “Until now we knew about the existence of three important women in his life: Ana Franca de Rojas, with whom he had a daughter called Isabel de Saavedra; Catalina de Salazar y Palacios, who he married in 1584; and Jerónima Alarcón, on whose behalf Cervantes acted as a financial guarantor in 1589,” says Cabello. “All we know about Magdalena Enríquez is that she was a baker and from Seville. She was probably a widow, because this was the only way that she could have collected Cervantes’ salary if he was away working in a different district. They must have had some kind of relationship.”

Meanwhile, the archbishopric of Madrid has given the go-ahead for the second phase of a project to identify the remains of an adult male that may be Cervantes buried in the capital’s Trinitarias convent. The novelist is believed to have been buried somewhere inside the convent on April 23, 1616. The body of Miguel de Cervantes, who died at the age of 69, reportedly showed signs of a gunshot wound to his chest sustained during the Battle of Lepanto. The bones of his left hand were also badly damaged during the clash. If the bones match these deformities, they could help support the theory that the remains do indeed belong to Cervantes.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.