The horrors of Cádiz’s floating jails

Nine prison ships set up in the city's bay held Napoleonic war prisoners in appalling conditions

Wars do not end with white flags. Their effects are felt well after victory is proclaimed or defeat accepted.

Lourdes Márquez, a Cádiz-based historian and an expert on the Battle of Trafalgar – which pitted the combined French and Spanish fleets against the British Royal Navy in 1805 – decided to find out what happened to the men who fought on Spanish territory during the early 19th century, a turbulent period that saw France and Spain partner as allies against Britain in the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

What she learned is that as many as nine decommissioned ships served as floating prisons in the bay of Cádiz at one time. At a recent lecture in Villanueva de la Reina (Jaén), Márquez detailed the harsh living conditions of the prisoners, many of whom died onboard, although a few did manage to escape.

The start of the investigation was a commission she received in 2005, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar. Márquez was asked to find out what had happened to the shipwrecked vessels. “I realized that a lot had been written about military tactics, but very little about the people who were involved,” she says.

There was hardly any food or drink. Some testimonies described incidents of cannibalism”

The story was so fascinating that she kept on researching. And what emerged is that the French who were captured at Poza de Santa Isabel, Villanueva de la Reina and Bailén, who had by then become Spain’s enemies after previously allying with it at Trafalgar, ended up inside these ships, which are known technically as prison hulks.

“The Spanish authorities faced a real problem with all these war prisoners that kept coming in,” says the historian.

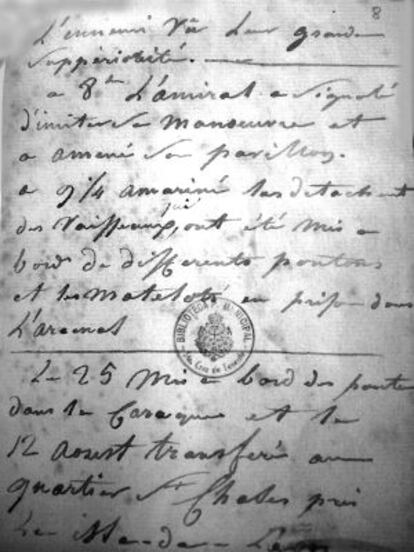

Eventually, they decided to convert nine old ships that were no longer seaworthy into prison ships. A map she discovered inside France’s National Library showed the locations of the hulks.

Márquez describes life on board the boats in Recordando un olvido, which features illustrations by Adolfo Valderas. “Conditions were appalling. Many people called them floating coffins. To the prisoners of [French naval commander François Étienne de] Rosily’s navy were added the troops led by General Dupont, who fell in Bailén.”

Although there was no existing literature on the subject, Márquez was able to locate testimony from French soldiers who survived imprisonment in the Bay of Cádiz – people such as Michel Maffiotte, Henry Ducor and Claude Étienne Henry Bernard, Marquis of Sassenay.

The ships were 60 meters long and 15 meters wide, and held as many as 1,000 prisoners each.

“There was hardly any food or drink. Some testimonies described incidents of cannibalism. There were diseases such as scurvy,” notes the historian.

So many corpses were being thrown overboard that an unexpected problem emerged. “The practice had to be banned, because fishermen were becoming suspicious of the enormous fish that swam in those waters filled with putrefied bodies,” she adds.

Yet even here, there was some space for leisure and cultural events. Besides the cardplaying and the shadow plays, upper-class prisoners on board the Castilla were treated to concerts and plays that attracted Cádiz’s bourgeoisie, who arrived by boat for the performance.

“There were Mozart and Cherubini repertoires, and opera buffa pieces,” says Márquez.

A clarinet player named Perret obtained his release on condition of playing to an English official.

Life aboard these prison hulks even served as inspiration for an opera of its own, Les pontons de Cadix, which premiered in Paris in 1836.

A point came when the number of prisoners was so huge that a decision was made to transfer them elsewhere. In 1809, a thousand men were taken to England, 1,500 to the Canary Islands and 5,300 to the Balearic Islands. Of these, 4,500 were abandoned on the island of Cabrera.

Lourdes Márquez underscores that of the 24,776 military and civilian prisoners held in Cádiz, only 7,082 survived. And those who did often lost their sanity, as ascertained by the German historian Hans-Dieter Zemke, who collected information about French soldiers who died at Sanlúcar hospital between 1810 and 1812. “They ended up in the madhouse or doing humanitarian work as priests.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.