A $2,600 fine for dancing on Diego Rivera’s grave

An actress has thrown a party among the tombstones of a number of illustrious Mexican figures

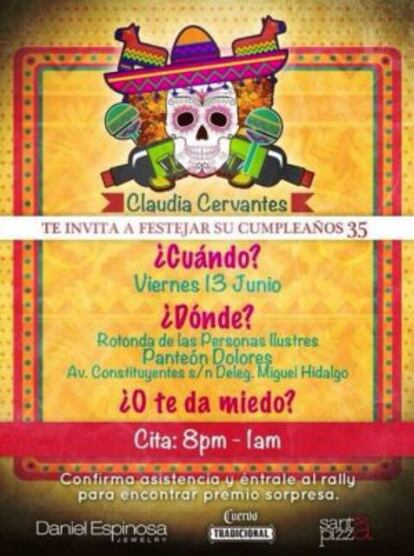

Some of the most important figures in Mexican history and culture are buried in Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres in Mexico City, including Diego Rivera, Juan O’Gorman, Agustín Lara, Amado Nervo, Rosario Castellanos and other Mexicans whom the country supposedly respects deeply. The silence around the mausoleums contrasts with the general frenzy in the city, and its atmosphere must have also been in contrast to the sound of those mariachis Claudia Cervantes decided to bring. The actress held her birthday celebrations on July 13 in the Rotunda, to “celebrate life where death lives.”

Cervantes brought lights, chairs and liquor to the cemetery. The party even had sponsors, and Cervantes received “permission” from Miguel Hidalgo, the richest municipality in Mexico City where the business magnate Carlos Slim lives and which falls under Víctor Hugo Romo’s jurisdiction. Romo is a member of the largest leftist party in Mexico. The Party of Democratic Revolution (PRD) has its main stronghold in Mexico City.

The actress, who has told every celebrity gossip magazine that interviewed her that former President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (2006-2012) is her uncle, invited one of the most widely read weeklies, TVNotas, to the party. “How original,” the publication wrote. “Since Friday 13th fell on the night of a full moon, Claudia Cervantes wanted to celebrate her 35th birthday in a pantheon!”

“We all laughed, overcame our fears and had a great time,” the birthday girl told the weekly magazine. The article was published on June 24th.

The images show a group of people toasting between the tombstones of the muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco. Some of the guests were on motorcycles. There was even a scavenger hunt among the mausoleums. The actress herself appears in one of the photos in a provocative pose on top of the tomb of the writer and diplomat Rosario Castellanos. Her son, Gabriel Guerra Castellanos, said in an angry note on Twitter: “Bold-faced lies and half-truths run through what @cervantesclau [Claudia Cervantes] and @vromog [Romo, head of the municipal delegation] say.” The indignation was unanimous among the descendants of the deceased presidents, poets, painters, musicians and philosophers.

That a supposedly ordinary Mexican citizen could organize a party in one of the supposedly most respected places in Mexico raises many questions. Some of them have been repeated over and over since the newspaper, La Jornada, published the story that TVNotas originally covered two weeks before. Is La Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres available for private events? Who is legally responsible for the Rotunda? Was there any damage? How will those responsible be punished? In order to answer some of these questions and understand the mysteries of the story one must explore the many and varied contradictions of Mexico.

La Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres is in a state of neglect. Although the National Anthropology and History Institute (INAH) said this week – once the scandal had exploded – that the party did not cause damage to the graves, time has caused serious deterioration to the site. Some of the mausoleums have mold. Others have broken stained-glass windows and some of the busts are dirty and rusted. Others are missing letters.

In order to visit the site, one must follow a series of directions. A guard supervises to make sure visitors respect the rules. A sign reminds them that professional photographs are prohibited without permission.

The Interior Ministry is responsible for maintenance at the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres. The ministry offers a virtual walk around the mausoleums on its official website. The INAH is also responsible for the tombstones of the late presidents, painters, poets and musicians who made Mexico proud. No restoration project may be undertaken without the institute’s permission. But, the Rotunda is part of the Panteón Civil de Dolores, which falls under the Miguel Hidalgo municipality.

When the scandal erupted, all fingers pointed to the Miguel Hidalgo administration. Mexico City is divided into 16 boroughs. The most populous, Iztapalapa, has 1.8 million residents, more than Barcelona. The juxtaposition of the working-class district of Iztapalapa and Miguel Hidalgo reflects the disparity in Mexico, a country where the second-richest man in the world lives alongside 53.3 million people in poverty. There are 300,000 residents in Miguel Hidalgo and some of the country’s richest citizens live there. The district is also home to the headquarters of several large Latin American corporations and most of the embassies in the country.

La Miguel Hidalgo, as locals call it, is run by Víctor Hugo Romo – a man who moves around the city on bicycle, carriers bicycle-shaped business cards and who told the newspaper Reforma that the controversy had helped “draw attention to the Rotunda,” and now “more people want to go.” Romo said Cervantes was an acquaintance because she had come to several of his political events, joined him in various speeches, and even sang at his public presentation of annual activities. Romo fired one of his employees, Rafael Del Val Ruiz, whom he said gave the group permission, allegedly without his – Romo’s, the municipal leader’s – knowledge. Val del Ruiz said the opposite in a recording obtained by El Universal newspaper. “We don’t lift a finger without [Romo’s] consent,” he said. “This is total crap! How could you hide these things?”

On Monday morning, Romo appeared before the press and showed a letter signed by Val del Ruiz where he himself said he authorized the party that led to his dismissal without consulting his boss. The leftist politician who oversees the administration of one of the richest areas in Mexico resolved the issue by saying that Cervantes had paid a $2,600 fine, less than a quarter of the average salary of a Miguel Hidalgo resident. She was fined for violating the permit she had been given.

The actress and singer later said: “We all have taken a wrong turn at some point in our lives.”

Translation: Dyane Jean François

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.