“Gabo” fans converge at novelist’s Mexico City home moments after his death

García Márquez will be cremated in a private service, says family spokeswoman. Funeral honors are scheduled to be held on Monday at Mexico City's Bellas Artes

At 144 Calle Fuego, in south Mexico City, a young girl wearing jeans and a black sweatshirt left a bouquet of daisies in front of the house at around 3.30pm last Thursday. At school, Mónica Hernández was assigned to read One Hundred Years of Solitude; it was an assignment she loathed. But years later, when she received the special edition published by the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), she immersed herself in rereading the 400-page epic novel.

Hernández was one of the first fans to arrive at Gabriel García Márquez’s home shortly after he died at the age of 87. It was an almost like an apologetic gesture for her youthful aloofness, but more importantly she was there to pay homage to one of the greatest Spanish-language writers of the 20th century.

It had been known since that previous Monday that García Márquez had been receiving palliative care at his home in the affluent Mexico City suburb of San Ángel. Since then, a barrage of reporters and camera crews had been camped outside his colonial-style dwelling that is covered with bougainvilleas at the entrance. Once in a while, a fan would walk up to inquire about the Nobel Prize-winner’s health, and they would walk away crushed after being told that the outlook wasn’t good.

At 2.56pm on that sunny Holy Thursday, Mexican journalist Fernanda Familiar – a close friend of the Colombian novelist and his wife Mercedes Barcha – arrived in tears and went inside without saying a word to her waiting colleagues. It was the first clue that one of the world’s literary greats had died.

Journalist Fernanda Familiar arrived in tears. It was the first clue that the world’s literary great had died

Five minutes later, Colombian writer Guillermo Angulo arrived by taxi carrying a suitcase, white bag and a hunting cap. He also went in without speaking to reporters. Shortly afterwards. Genovevo Quiroz, García Márquez’s assistant, emerged to give instructions to two policemen who immediately began to close off the street.

María del Carmen Estrada peeked her head out from her home next door to García Márquez. She recalled the day that she threw her arms around him when she bumped into him. “I never read any of his books,” she said, “but the people loved him a lot, and I grew very fond of him. He was an exemplary neighbor.”

García Márquez’s body will be cremated at a private ceremony, announced María García Cepeda, director of Mexico’s National Fine Arts Institute, who spoke on behalf of the family in front of the writer’s home. She was accompanied by Jaime Abello Banfi, another good friend who serves as director general of the Ibero-American New Journalism Foundation. If anyone had the right to address the literary giant as “Gabo” – the nickname he was fondly known by throughout the world – it is these two people.

A gray hearse arrived at around 4.35pm to take his body to a nearby funeral home. The vehicle’s logos seemed to have been hastily covered to hide the funeral home’s name but it was still clearly visible through the transparent paper. García López is a small private mortuary that doesn’t hold large services.

But just like Mexico’s bigger-than-life figures – such as legendary comedian Mario Cantinflas Moreno – García Márquez will be given an honorary service on Monday afternoon at Mexico City’s renowned Fine Arts Palace, which is simply known as Bellas Artes. It is the highest honor Mexico can bestow on one of its late greats. Even though García Márquez was born in Colombia, he had made Mexico City his home for decades.

“I never have read any of his books, but the people loved him a lot, and I grew very fond of him,” said a neighbor

In his hometown of Aracataca, Colombia, dozens of people gathered outside his family home Thursday night to light candles, pray and remember the Caribbean town’s most famous son.

Back in Mexico City, a police official by the name of Cantellano was in charge of the officers who guarded Fuego street last Thursday. He ordered barriers to be put up and sent in a small contingent to keep reporters and others from getting too close to the entrance of García Márquez’s home, garage and driveway.

“We are on an important mission,” he said in a low voice. His officers stood guard for hours.

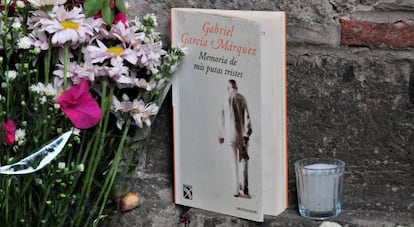

Once in a while as they took a break, an officer was seen helping a Gabo fan place flowers, books or candles in front of the doorway, which was soon transformed into a sprawling altar dedicated to the Colombian writer’s memory. One young policeman by the name of García said he didn’t know who the novelist was – “I have no idea.” But because he and his fellow officers were ordered to provide tight security, García realized it was an important moment. “I didn’t know who that man was but I will soon be reading one of his books.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.