Priest who witnessed 1,700 executions gets his own square in Zaragoza

Unlike his superiors, Gumersindo de Estella was repulsed by the mass killings The deaths took place between 1936 and 1942 against the cemetery walls in Torrero

“‘So many men to kill three women!’ yelled one of them. Shots rang out. I gave them absolution, and before the lieutenant fired the coups de grâce, I walked away like an automaton.”

The firing squad was made up of 24 men. The three women were Selina Casas, Margarita Navascués and Simona Blasco. And the witness to this atrocious scene was Gumersindo de Estella, who saw as many as 1,700 executions against the cemetery walls of the town of Torrero in Zaragoza between 1936 and 1942.

“As a priest and a Christian, I felt repugnance at so many killings and I could not approve of them.” He could not prevent them, either, but he did leave written testimony in a moving diary that has earned him a square named after him inside Torrero’s cemetery.

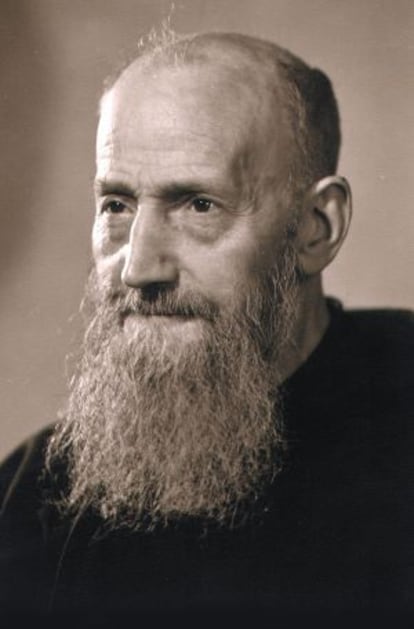

Gumersindo de Estella, the religious name adopted by Martín Zubeldia (1880-1974), rode in the trucks that took the victims from the local jail to the cemetery wall. There he administered the sacrament known as the Anointing of the Sick, part of the last rites, to the dying victims, in between the first volley of shots and the coups de grâce.

This priest also witnessed the stealing of children that went on, as his diary entries detail: “Show some compassion, don’t take her from me! Let her be killed with me!,’ screamed one. ‘I don’t want to leave my daughter with these executioners!,’ screamed the other. A fierce struggle ensued between the guards who tried to forcefully pull the children away from their mothers’ breast, and the poor mothers who defended their precious ones tooth and nail.”

The babies were just a year old. They were the daughters of Selina Casas and Margarita Navascués, who were accused of trying to escape into Republican territory the day before, on September 21, 1937. Nuns took the children in after their mothers were killed.

“Some of my superiors displayed extraordinary delight at the unfolding events, and even clapped and cheered”

“My attitude was in sharp contrast with that of other men of the cloth, including some of my superiors, who displayed extraordinary delight at the unfolding events, and not only approved of them but even clapped and cheered quite frequently,” wrote Gumersindo de Estella in his diary.

It was precisely a confrontation with his superiors that landed the priest in Torrero prison, where he was the chaplain. Zubeldia argued with Father Ladislao Yabar, who would ceremoniously announce things such as: “Today we will eat hens confiscated in Guipúzcoa by our brave requetés [militia groups fighting for traditional values].” As punishment, he was transferred from Pamplona to Zaragoza. It took him nearly a year to get Franco’s portrait taken down from the altar in the chapel. He had time off for a while because of an ulcer and when he returned to his post, after the end of the war, the executions were still going strong: there were nearly 700 after 1939. The difference was that by now there were sand bags behind the wall, because the bullets had pierced it and reached all the way to the niches holding funerary urns behind.

Not one day went by without a killing, not even on Christmas Eve

In total, over 3,543 republicans were executed against that wall between July 19, 1936 and August 20, 1946. Not one day went by without a killing, not even Christmas Eve. In October 2010 the cemetery inaugurated a memorial to the victims: a spiral made up of plaques with the names of each one of them.

“His diary is a unique and extraordinary document,” explains Julián Casanova, professor of contemporary history and author of La Iglesia de Franco (or Franco’s Church). “It shows the uneasiness of a man of the Church as he witnesses the fervent, warrior-like spirit of an institution that has placed itself at Franco’s service.”

Zubeldia concealed his diary until shortly before his death in 1974, when he told other priests about it.

“They consist of five notebooks, which to us are a treasure,” explains Father Tarsicio de Azcona, 90. “He suffered greatly. He was a man of the people, a popular missionary.”

The diary was published in 2003 thanks to Azcona and another member of the Capuchin order, José Ángel Echevarría. The tribute came this week, on the 75th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, as a result of a unanimous agreement by the members of Zaragoza City Council.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.