Brazilians scramble to uncover their Sephardic roots

Thousands rush to examine family trees in wake of Spain's plans to give passports to Hispanic Jews Many are pinning their hopes on a phony list of surnames

The phrase is heard all over Brazil these days, with only slight variations: “I never thought this would ever happen, but I’m going to try to obtain Spanish citizenship!”

Take the Spanish government’s proposal to grant nationality to people who can prove their Hispanic-Jewish roots, add a (phony) list of more than 5,200 allegedly Sephardic surnames, including very common ones in Brazil such as Oliveira and Silva, and shake the whole thing up with the power of Facebook. The result is a huge rumor that not only reveals the Jewish community’s interest in Spain’s attempt at redressing a historical wrong, but also underscores many Brazilians’ desire to obtain European citizenship.

The list of surnames allegedly proving that families are descended from Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 has spread like wildfire around several Latin American countries, and even though the Spanish Justice Ministry has issued a statement denying its authenticity, it keeps cropping up on the social networks as though it were bona fide. Meanwhile, rabbis and Jewish associations have been flooded with hundreds of requests for information by potential applicants.

A spokesperson for the Jewish-Brazilian Archive admitted it lacked the resources to deal with this sudden interest in people’s Jewish roots. “This story is ruining our research. In two days we have received 20 requests involving genealogy. We don’t have the capacity to cover that kind of demand.”

In 2008 there was a similar race to the Polish consulate to obtain citizenship”

Antón Castro Rodríguez, who teaches at the Center for Education and Human Sciences, has an explanation for the overwhelming interest that Brazilians have shown in an initiative aimed at offering symbolic redress for the expulsion of the Jews from Spain.

“There is a deep-rooted belief that Brazil has a large number of people who are descendants of Portuguese New Christians [Jews who converted to Christianity after persecution by the Inquisition but secretly maintained their faith]. This creates the feeling that there are many descendants of these Jews. A lot of genealogy studies show the Jewish roots of illustrious people such as [musician and writer] Chico Buarque, for instance.”

Brazil’s official Jewish community numbers around 110,000.

While the basis for the rumor might be true, the Spanish government’s proposal still needs to overcome several parliamentary hurdles, and in any case will not translate into an indiscriminate handing out of passports.

As it stands now, the initiative promises Spanish citizenship to individuals who can “certify their Sephardic condition through providing proof and evidence, besides their ties to Spain or to Spanish culture, in the broadest sense,” said a source at the Justice Ministry.

Rabbi Samy Pinto, of the Ohel Yaacov synagogue in São Paulo, confirms that he has already had nearly 100 families come to his office looking for their roots and the documents necessary to prove them. “What brings them here is a purely emotional past,” he explains. “In the Sephardim’s psyche, the memories were never erased. They are extremely nostalgic. They love to bring up the past through music, great thinkers and liturgy. There is a relationship of love between Sephardic Jews and their countries of origin, which is clearly manifested by this episode.”

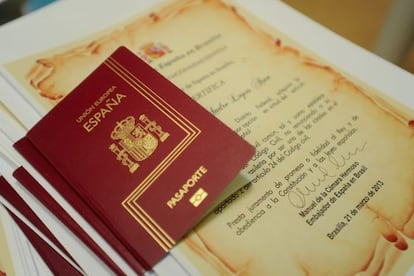

Yet the rabbi also regretted that about a quarter of his visitors are not so much moved by nostalgia as by the ambition to secure a European document that would allow them to live and work on the continent. “There is a race underway to obtain that passport,” he says.

“There is a belief, which is well founded to some degree, that Jews are cultured, successful people. So having Sephardic origins is highly valued, especially if you add the possibility of acquiring Spanish citizenship,” adds Professor Castro, noting that Brazilians are strongly prejudiced against the Portuguese, who controlled the country from 1500 to 1822. “There is a sense of pride in being descended from New Christians. That is to say, not being descended from Portuguese but from Jews.”

Some are moved less by nostalgia and more by the ambition to secure European citizenship

Ricardo Berkiensztat, executive president of the Israeli Federation of the State of São Paulo, notes that this is not solely a Spanish initiative. In 2008, “there was a race to the Polish consulate to obtain citizenship for the same reason,” he says in perfect Spanish.

For years, Spain had been analyzing the best way to grant citizenship to the descendants of Sephardic Jews. It has been a personal commitment of King Juan Carlos, who has expressed it on many occasions. Representatives of the Jewish community in Brazil – which is very influential but no larger than the one in countries such as Venezuela – have known through the Spanish ambassador that the initiative has been in the pipeline for the last two years. It was Crown Prince Felipe who personally confirmed Spain’s willingness to “redress a historical wrong” during his last visit to Brazil a couple of weeks ago.

The Jewish presence in Brazil dates back to the Dutch occupation during the 17th century, explains Professor Castro. But the community grew significantly with the mass arrival of Sephardic Jews from Morocco, who settled in the northern states of Amazonas and Pará in the late 19th century.

Another wave of Sephardic Jews from the Iberian peninsula landed there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “They mostly settled in the states of São Paulo and Río de Janeiro, and formed a very important community,” notes Castro. “The thing is, Brazil already had more traditional communities of Ashkenazi Jews [from Central and Eastern Europe]. So, because of the high degree of westernization of the Sephardic Jews, this latter community became nearly invisible.”

In the last seven years, Spain has awarded citizenship to 746 Sephardic Jews, mainly Turkish and Venezuelan but also a few from North Africa and Latin America. But the concessions were made on a case-by-case basis. There are more than 3,500 such applications still pending a reply. When the new law goes into effect, it is expected that at least 150,000 new applications will be sent in.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.