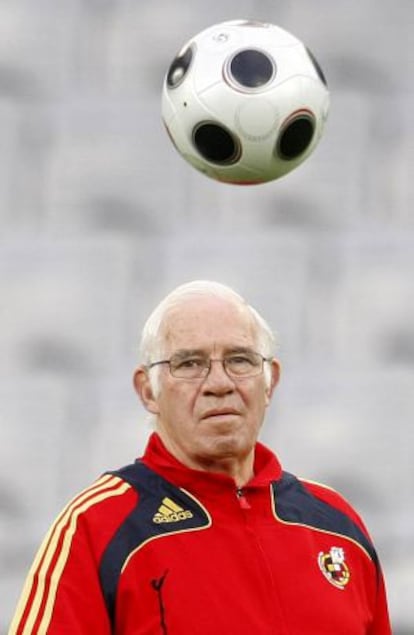

Luis Aragonés, inventor of La Roja

Soccer coach who brought Spain success leaves behind many happy memories after death at 75

“The ball is music and has to be accompanied properly.” “Iker, the goalkeeper also has to know how to play it. You must take good care of the ball,” Luis Aragonés, who died early on Saturday morning age 75, could be heard to shout in the training sessions prior to the match in which he would turn Spanish soccer history on its head by tossing the ball to a group of small players with the instructions to keep passing. Spain was about to play Denmark in a qualifier for the 2008 European Championship, which the team would go on to win, and Aragonés picked the trio of Andrés Iniesta, Cesc Fàbregas and Xavi — all players with a Barcelona pedigree. The revolution had started. The 1-3 win in Aarhus helped to consolidate the idea of possession-based soccer, an approach that would lead La Roja to more triumphs, with Vicente del Bosque in charge, in the 2010 World Cup and again at Euro 2012.

The multitude of former teammates and fellow coaches who paid their last respects at the Tres Cantos funeral home on Saturday agreed that Luis Aragonés’s greatest legacy was to have established a style which enabled a talented generation of players to dominate the sport. Leukemia was the reason why so many people had cause over the weekend to remember one of the most charismatic, controversial and influential figures in Spanish soccer.

Aragonés was born in 1938 in Hortaleza, the son of a halberdier in the court of King Alfonso XIII who would later move into the transport business. Luis’s father was nothing short of a celebrity in what was then a village outside Madrid, where a street bears his name, Hipólito Aragonés, as a sign of gratitude for service offered to the people in what were terribly hard times in the postwar era. When his father died, 14-year-old Luis took charge of the only van there was in Hortaleza at that time. Along with his nine siblings, Aragonés worked the family business as the only way to get ahead. Ángel Ramos, the village butcher, discovered his footballing talent and so began a successful career as a player, first at Getafe, followed by a string of clubs including Real Madrid and Betis, before he found what would be his spiritual sporting home.

At the age of 26 Aragonés joined Atlético Madrid, the club where he would become a legend even before the heroics of his Spain team that night in Vienna. He was an admirer of Waldo, a Valencia player who excelled from free kicks. When another player, Urtiaga, made the move from Valencia to Atlético, Aragonés sidled over to him and said: “You have to show me how to take free kicks like Waldo.” That dead-ball strike, executed to perfection, in the European Cup final against Bayern Munich in 1974, which Atlético would end up losing in a replay, is the best remembered image of Aragonés as a player. The bend on the ball’s trajectory as it cleared the German wall, the legendary keeper Sepp Maier stood stock still, and Luis, raising his arms in celebration even before the ball hit the back of the net, are images burned onto the retina of many Atlético fans and Spaniards of that era in general.

Aragonés’s powerful running also helped the midfielder score a lot of goals from open play, arriving in the area behind the strikers. In 1970 he was a joint top scorer in La Liga with 16 goals. He won three Liga titles and two cups with Atlético as a player, and represented Spain 11 times.

When the Argentinean Juan Carlos Lorenzo was dismissed as Atlético’s coach at the start of the 1974-75 season, the club offered Aragonés the reins, even though he was still a player. “I didn’t feel vertigo because I was already thinking about coaching, even though I was going to lead people who had until the day before been my teammates,” he recalled in a recent interview with EL PAÍS, in which Aragonés also explained why it was impossible to hear a bad word about him from any of the hundreds of players he has worked with. “The key to lasting so long is to be true. Sincerity trumps everything. A player will not tolerate being lied to.”

On the coach’s bench, Aragonés finally forged the character which became an honorary member of millions of Spanish households. The tracksuit as uniform; the wonky glasses; the use of the third person singular: “Luis did not say that,” and other traits were joined by oft-repeated anecdotes from his personal management style. His speech to a disaffected Romario at Valencia was caught on camera and “Look into these eyes of mine,” became a catchphrase among soccer fans. Then there was his dressing down of Samuel Eto’o at Mallorca after the player had shown disgust at being substituted. The Cameroonian said at the time that it had been like a “father-to-son sermon,” and repeated the sentiment on Saturday after hearing of Aragonés’s death. “He was like father to me,” the now-Chelsea player said. The “motivational” chat with José Antonio Reyes, telling the Spain squad member that he was better than “ese negro de mierda” in reference to the Andalusian’s Arsenal teammate, Thierry Henry, sparked controversy, but it should be understood as just another example of how he liked to get under his players’ skins to bring out the best in them. Of his coaching career, which saw him take charge of Atlético on four separate occasions (one league title, three cups, a supercup and a second division championship) as well as a host of other teams, Aragonés said: “I attach as much importance to the third place with Mallorca as winning the cup with Barcelona and saving Oviedo from relegation.”

Aragonés is survived by his wife Pepa, five children and 11 grandchildren.