A poet beloved by his countrymen

Cervantes Prize winner José Emilio Pacheco dies in Mexico City at 74

Mexican poet José Emilio Pacheco died in Mexico City on Sunday after being admitted to hospital the previous afternoon. He was 74. "He went quietly, he was at peace," said his daughter Laura Emilia Pacheco, who confirmed the news.

A poet, storyteller, essayist and translator, Pacheco was a simple man. His public image was that of a poet without pretensions. When he received the Cervantes Prize in Spain in 2010 he had this to say about those who went around saying he was one of the best Latin American poets: "But I'm not even one of the best in my neighborhood. Don't they know that I'm a neighbor of Juan Gelman's?"

The two writers both lived in Mexico City's Condesa neighborhood. In recent times, they barely saw each other because they were both too infirm to stroll around, though last April they managed to coincide at a book presentation: "I would see you more if you lived in Buenos Aires," Pacheco told Gelman.

The Argentinean poet beat his friend Pacheco in crossing to the other side by a few days, dying at the age of 83 on January 14. Two weeks later it was time to say farewell to Pacheco, another of the great Latin American poets of recent decades. The late Mexican author Carlos Fuentes wrote this about him in 2009: "His work is universal work, and is part of the splendor of timeless literature."

Pacheco was a discreet idol. He rarely appeared in public, but was always present at the altar of literature devotees. One of his poems, Alta Traición (High treason), was and remains one of the key references for understanding Mexico and the contradictory feelings it generates among many Mexicans:

No amo mi patria.

Su fulgor abstracto

es inasible.

Pero (aunque suene mal)

daría la vida

por diez lugares suyos,

cierta gente,

puertos, bosques de pinos,

fortalezas,

una ciudad deshecha,

gris, monstruosa,

varias figuras de su historia,

montañas

- y tres o cuatro ríos.

(I do not love my country

Its abstract brilliance

is intangible

But (though it sounds bad)

I would give my life

for ten of its places,

certain people,

ports, pinewoods,

fortresses,

a broken city,

gray, monstrous,

several figures from its history,

mountains

- and three or four rivers.)

Pacheco studied law and philosophy at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. He was the translator of, among others, Tennessee Williams and T. S. Eliot, contributed to newspapers, and wrote essays, short stories and novels, such as Morirás lejos (1967) and Las batallas en el desierto (1981). But poetry was his genre, with most of his work collected in the volume Tarde o temprano (Poemas, 1958-2000).

Writing was Pacheco's raison d'être. "The language into which I was born constitutes all the wealth I have," he said in 2010 when he picked up the Cervantes."

Before that, in an interview with EL PAÍS in 2009, he talked about the personal effect that coming up with a good phrase had on him: "One feels very satisfied, yes, for sure."

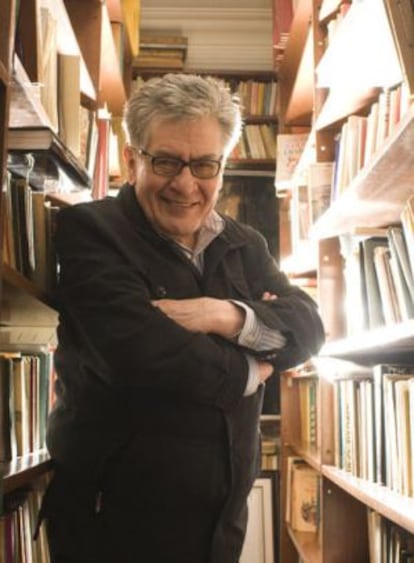

While he wrote excellent verse, he was no dazzling orator. He used normal and humble words in keeping with his appearance as a quiet man, with white hair and square glasses. "He didn't use solemn phrases, he didn't exclude others, students surrounded him, the girls were infatuated with him, he didn't build a following, he didn't try to overwhelm with his presence, his remarks were homely: 'I thought I was going to miss the train,' 'I couldn't find a taxi...'" wrote his compatriot Elena Poniatowska, winner of last year's Cervantes Prize, of him in EL PAÍS.

Another detail that defined Pacheco's incompatibility with public show occurred at the Cervantes ceremony. As he entered Alcalá de Henares University, his trousers fell down. When the ceremony finished Pacheco said he had never dressed up as "a penguin" before and didn't realize that it would have been good to put on some braces.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.