Forty years of censorship

A new book recounts the alterations made to movies and their posters by censors during the Franco regime

The censors' scissors were never idle during the Franco dictatorship. The movie industry, with all its provocative and insinuating images, was a great source of headaches for the watchdogs of public morality - especially since going to the movies was the main form of entertainment for society in the wake of the Spanish Civil War.

And so censors were very careful to ensure that any film that was screened in Spain contained no negative influences on issues such as religion, politics, the army, prostitution, divorce or adultery.

Sex became a real obsession for the regime, and it was persecuted with all the weapons at the censors' reach. Poster draftsmen and movie theater impresarios had to really stretch their imaginations to make their billboards reflect the American, English or French realities. This was not always achieved.

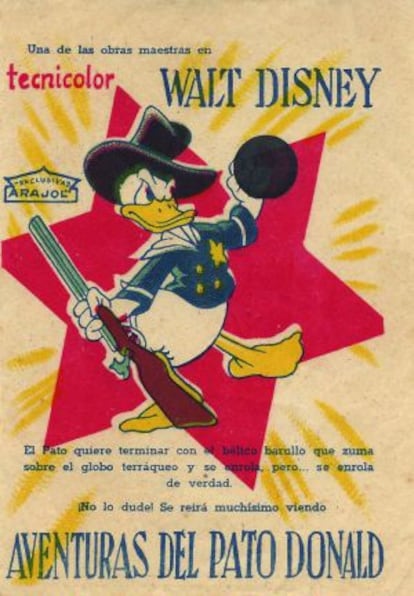

A new book, La censura franquista en el cartel de cine (or, Franco's censorship in movie posters), by Bienvenido Llopis, analyzes 40 years' worth of censorship in Spain through films. The conclusion is that cleavages were reduced, legs were covered up, and scenes with beds in them were avoided altogether.

Legs were covered up, and scenes with beds in them were avoided altogether

"Movies were banned and stills were cut out," Llopis notes. "But it was just as important to control movie advertising. Major Hollywood stars who embraced the Republican cause - James Cagney, Joan Crawford or Robert Montgomery - had their names pulled from Spanish movie posters, while titles that might suggest a double meaning were changed."

Llopis spent more than three decades acquiring posters, programs and magazines that reveal the work of the draftsmen and censors of the era.

"It was no easy task because many documents had been lost. There are six of them that I was unable to obtain, but they are included in the book courtesy of their owners," adds the writer and researcher.

The book includes movie posters, magazine covers, comic strips, novels, news stories, photographs, postcards and collectible picture card albums showing the work of censors who became nothing short of fashion designers in their efforts to please the regime. Esther Williams, Ava Gardner, Marilyn Monroe, Rita Hayworth, Sophia Loren and Gina Lollobrigida were seen in Spain wearing dresses that had little in common with their original designs.

The idea for the book came to Llopis one Sunday morning at the Madrid flea market, the Rastro. There he was, sitting at his stand, selling movie memorabilia, when a man showed up saying he had a program for the movie Camino de Santa Fe, which had obtained the censors' approval everywhere in Spain save for the city of Burgos. The archbishop there insisted that Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland's kiss be hidden with a seal.

The man turned out to be the owner of a movie theater in Burgos, and he promised to return with the movie program. "I waited for him for many Sundays, until one day he showed up again, and when I saw [the program], I thought I have to make a book out of this. I didn't imagine it would take this long. I started in 1985, and just finished now."

The final blow to Spanish censorship was delivered on December 1, 1977 by a government decree under Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez. Poster makers breathed a collective sigh of relief as a period of creative freedom opened up before them. By then, however, even Donald Duck had fallen on the censors' bad side. The reason? At one point the cartoon character had his fist up in the air, and children's impressionable minds might have compared it with the Communist salute.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.