A bitter harvest in Marinaleda

The antics of a crusading mayor of this Andalusian rural utopia have just earned him a jail term

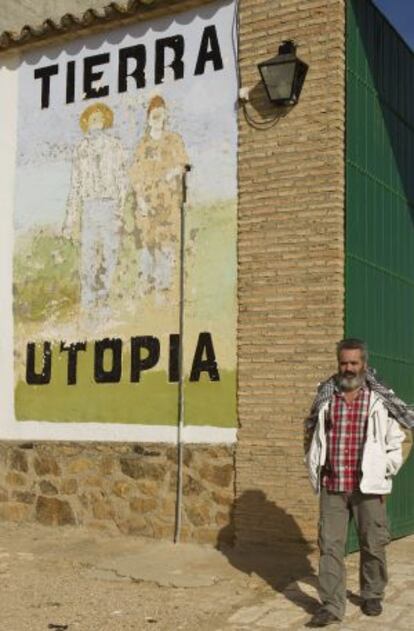

Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo is tired. The man who last year organized supermarket robberies to draw attention to the plight of families who couldn’t afford to shop in them has been burned by the media attention he provoked. Now, Gordillo is recovering from an excess of camera flashes in Marinaleda, the Andalusian agricultural town he has been mayor of since 1979.

On a crisp November morning, Gordillo is visiting the olive oil mill. The machinery lies silent because the 70,000 tons of olives needed before it can be fired up have not yet arrived. The teams of pickers have not been well organized. “We’ll have to have a meeting to sort it out,” Gordillo tells Manuel, the manager.

Meetings. Everything in this collective community of 2,786 inhabitants is resolved by meetings, the better to preserve a rural utopia created in the 1980s when the Andalusia regional government expropriated 1,200 hectares of land from the Duke of the Infantado and handed it over to day laborers who until then had been trapped in a feudal regime. Marinaleda is little more than one long street of low-rise buildings, which over the past year has received groups of people from Greece, Latin America and the four corners of Spain to write messages of support on its walls. But recently the revolutionary messages have jockeyed for space with other slogans daubed in black: an extreme-right group recently paid the town a visit and left a number of written threats. Marinaleda has been in the eye of the storm for the last 12 months.

Sánchez Gordillo, 64, was in pensive mood that Thursday morning as he went for lunch. But when he returned his eyes were wide open: “I’ve just seen on the television that they’re going to give us seven months in jail. In 30 years of squatting this has never happened.” Gordillo is referring to the decision of the regional High Court to sentence him and three others for their occupation of the disused Las Turquillas Defense Ministry enclosure to demand that it be ceded to the nearby village of Osuna.

I’ve just seen on TV that they’re going to give us seven months in jail.”

The mayor is also a regional deputy for the United Left (IU) and a leading figure in the Andalusian Workers Union (SAT), whose leader, Diego Cañamero, was also sentenced by the court. Gordillo has run up almost a million euros in fines but has never before been given a jail sentence. There are plenty of proceedings open against him, including one relating to the supermarket raids of last summer, which prompted interviews with US journalists and an English writer to move to Marinaleda in order to research a book. But the price of the revolution is creeping up.

“They’re confused about us,” says Gordillo. “They don’t know what we stand for. We don’t want violence.” The political arm of SAT, which marries radical leftist policies with the rural anarchist tradition of Andalusia, is the Collective for the Unity of Workers — Andalusian Left Bloc, a potent force in the regional IU of which Gordillo is leader.

The Marinaleda model has attracted movements such as 15-M, which have collaborated in actions similar to the Las Turquillas occupation, such as the one at Somonte (Córdoba) where SAT hopes to repeat the utopian ideal with more modern-style activists. But as yet, nothing like Marinaleda has emerged. “It’s difficult,” Gordillo says with a melancholic air. “There are obstacles, misinterpretations and heartache.”

Despite its communist ideology, El Humoso cooperative is keyed into the logic of the market economy

Despite its communist ideology, Marinaleda’s El Humoso cooperative is keyed into the logic of the market economy and working to reduce costs and remain competitive. Only 30 percent of what is produced is marketed in its name. The remaining 70 percent is sold to other companies. Gordillo hopes to introduce crops such as leeks and chard, and to produce pre-cooked products. But credit, ethical banking and donations are all needed — the margins are narrow, and even more so in the middle of a recession that has seen the collective take in many former construction workers. In town meetings the talk is of reducing salaries, while outside critics have voiced accusations that Marinaleda lives off subsidies granted by a regional government that turns a blind eye to its excesses because of the halo of romanticism surrounding it.

The peculiarities of the town are numerous. Apart from those people who have private businesses or work their own land, every inhabitant earns exactly the same salary (1,200 euros a month for a 39.5-hour week), whether they work at the school or in the fields, as 50 percent of the population does. There is no local police force and the town hall has just seven employees.

Although Marinaleda promotes a leftist ideology, there are right-leaning newspapers in the bars, and religious imagery in the odd home. However, local Socialist spokesman Mariano Pradas says it would be wrong to think dissention is welcomed. Born in Marinaleda and an employee of the Estepa municipal street-cleaning company, Pradas insists he is a socialist at heart. He is a member of the unions and votes for the majority of Gordillo’s proposals because he supports improvements to the town. Even so, not one assembly goes by without residents calling him a fascist. “Because there is no room for even minimal criticism,” he says. “The problem is the conception of what ‘public’ means. I believe everything should be for everybody, including those who do not agree with you.” Pradas also condemns the way Gordillo distributes the common resources. “He shares out the work to the benefit of those who follow him.”

Marinaleda is a battle zone, and on the field Gordillo and his supporters do not take prisoners or seek reconciliation. Because of this, and because it is against the world, for better or worse, the Marinaleda model is special. Away from the shouting matches and the threatening graffiti, life goes on in a humble town of proud laborers, who, as the winter nights draw in, warm their living rooms with wood burners fueled by olive branches.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.