France’s Gypsies: the first behind wire fences

Even before the Nazis arrived, many of nation’s Roma were rounded up in a concentration camp

Montreuil-Bellay is a municipality near Saumur, one of the capitals of the department of Maine-et-Loire. This is home to the good old France, the France of the terroir, of the fleur-de-lys, of white folks who drink wine that was bottled half a century ago and who eat butter and mushrooms. This is the France that votes for Marine Le Pen, the stingy France of Balzac's Eugénie Grandet; the bellicose France of the Cadre Noir Riding School of Saumur. It is the France that takes its children to fundamentalist schools and obeys the châtelain, the lord of the castle, who holds more sway than the mayors.

In this medieval feud dotted with crenelated battlements, a certain event took place almost 75 years ago. This event was either exemplary or horrible, depending on one's point of view. In any case, the locals were so ashamed of it that for decades it was never talked about.

On January 6, 1940, a Spanish Republican Army captain named Manuel G. Sesma showed up in Montreuil-Bellay at the head of the 8th Section of the 184th Company of Spanish Workers, made up of 250 people. Sesma had left Spain toward the end of the Spanish Civil War in February 1939. In 1983, the captain told Jacques Sigot, a schoolmaster and local historian, that in six months the Spaniards lifted 19 kilometers of railroad tracks, "moving rails that weighed 0.7 tons with their bare hands."

Spanish soldiers were used to build a prison for "nomads and foreigners"

That piece of land was due to house the personnel in charge of a gunpowder arsenal, but the German advance made the French change their minds, and in June 1940 they ordered the construction of a concentration camp for "individuals without a fixed domicile, nomads and foreigners who have the Roma physique." The Spaniards just barely had time to build the underground prison, Sesma retells in Sigot's book Montreuil-Bellay, un camp de concentration pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale (or, Montreuil-Bellay, a concentration camp during World War II).

From November 8, 1941 to January 16, 1943, it became the largest concentration camp for Gypsies in all of France. But its story remained untold until Sigot discovered the ruins in the 1980s. These have been part of the national heritage since 2012, but they are not easy to find. Besides the underground prison, all that is left are the foundations, the flooring of one of the barracks, and three flights of stairs. The prison is shaped like a cave, and the rock still bears some names that were engraved by people with names such as Duval or Reinhard.

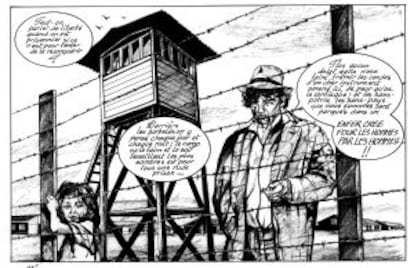

"Perhaps some cousin of the great guitarist Django Reinhardt," presumes Kkrist Mirror, a cartoonist and pro-Gypsy activist who was born in Saumur. In 2008, he published Tsiganes, a black-and-white graphic novel account of the history of Montreuil-Bellay.

Mirror, who rode up here from his home in Brézé on his Harley-Davidson, had personal reasons for taking an interest in the matter. "My father was interned in a German camp during the war. He just barely managed to escape, and I started drawing his story at the age of 10. Later I found out that right next to our house there was another concentration camp, run not by the Germans but by the French. And later I found out that my neighbors — the butcher, the carpenter — had worked there as guards. That is when I decided to do the book."

In 2010 Mirror was one of the artists who reacted to then-President Nicolas Sarkozy's attacks against the Roma by setting up an artistic group to raise awareness about this past of persecution. The godfather of this movement was the Roma filmmaker Toni Gatlif, who told the story in movies such as Liberté and Latcho Drom; other contributors included the cartoonist Emmanuel Guibert and the photographer Alain Keler.

"In France, persecution of Gypsies began significantly before the [Nazi] occupation," wrote the historian Marie-Christine Hubert. "Already in September and October 1939, the circulation of nomads was prohibited in several provinces. The Gypsies of Alsace and Lorraine were deported in July 1940 towards the free zone."

Those Roma shared camps with the Spanish republicans at Argelès-sur-Mer, Barcarès and Rivesaltes before being transferred in November 1942 to the camp at Saliers (near Arles), "especially created by Vichy for the Gypsies," notes Hubert.

This infamy was not exclusive to the Loire region, not even to France as a whole. The ghost of Gypsy-phobia has run up and down Europe along parallel lines to anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim sentiment for the last 10 centuries. The fear of those who travel in caravans, sleep out in the open and sing to the moon is an integral part of Europe's Christian roots.

France and Germany, bitter enemies in so many wars, shared this obsession. Ian Hancock, a professor at Texas University, writes in We Are the Romani People that the Gypsy hunt in Germany was a prelude of things to come: "During the 1920s, the legal oppression of Romanies in Germany intensified, despite the legal statutes of the Weimar Republic that said all its citizens were equal. In 1920 they were forbidden to enter parks and public baths; in 1925 a conference on The Gypsy Question was held which resulted in the creation of laws requiring unemployed Romanies to be sent to work camps 'for reasons of public security' and for all Romanies to be registered with the police."

These days, Gypsies continue to make headlines over the same stories - or rumors - as they did 500 years ago: if they have a blond child, it's because they steal children. Or else, as French Interior Minister Manuel Valls said, they are "culturally different and they don't want to integrate."

It's sad to see that anti-Gypsy racism is still politically profitable in France"

"And to think that in 2012 I voted for the Socialists!" exclaims Kkrist Mirror. "It's sad to see that anti-Gypsy racism still comes at no price and that it is politically profitable. It is sad because Gypsy [persecution] tends to be the first sign that something terrible is about to happen. When the Spanish republicans arrived in Montreuil-Bellay, France was not at war and there was no Vichy regime yet. The racial laws were approved by the Third Republic. The decree dates from April 6, 1940. But the first racial law of the 20th century goes back to 1912, two years before World War I. And it is still in force."

The Third Reich made background checks on Gypsies that mirrored ancestry questions asked of Jews in order to classify them as non-Aryans: if two of their great-grandparents were partly Gypsy, there was no saving them. To this day, there are only approximate figures on the Gypsy Holocaust — Porrajmos, or 'the devouring' in the Roma language — even though Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal wrote to Elie Wiesel in 1984 that Gypsies were murdered in a similar proportion to Jews; around 80 percent died in Nazi-occupied countries.

Hubert's own data indicates that between 1940 and 1946 at least 6,500 people lived inside 30 French concentration camps because of their real or perceived Gypsy ethnicity. "Their assets were expropriated and they suffered the worst material and moral precariousness."

In Montreuil, residents paid entrance tickets to go see them, explains Mirror in his book. The historian Hubert writes that "children received a Catholic education at the camps. And in extreme cases, they were separated from their parents and handed over to the social services or religious institutions to definitively extract them from a context that was viewed as pernicious."

Just as a Socialist government in France has not provided much help for the Roma community, so the liberation of France and the end of WWII did not bring about much improvement for the tsiganes, who remained interned at the Alliers camp, near Angoulême, until May 1946, nine months after the French liberation. Montreuil-Bellay had shut down much earlier, notes Kkrist Mirror: "When they transferred the Gypsies out, the camp director, a Pétain supporter-turned Résistance activist, decided to lock up all the prostitutes in the area and run a brothel. There was such a brutal syphilis epidemic that the women of the nearby villages demanded the camp be shut down."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.