The “artistic” blacklists of the Argentinean dictatorship

Raft of documents uncovered last week include names of writers, actors, journalists and musicians considered dangerous by military regime.

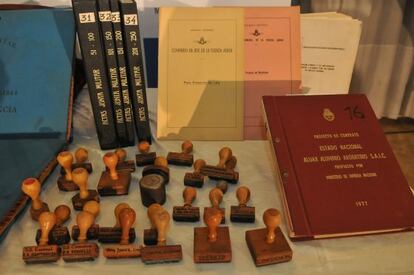

There were blacklists that included the artists and intellectuals Julio Cortázar, Héctor Alterio, Federico Luppi and Mercedes Sosa; there were also schemes to hold on to power until the 21st century, orders to transfer ownership of the country's only newsprint factory, instructions on how to field questions about missing persons from international organizations, and a formal letter by Hebe de Bonafini, president of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo activists, inquiring about the whereabouts of her two missing children. All this is part of some 1,500 secret files kept by Argentina's last military dictatorship (1976-1983), which were uncovered last Friday by Air Force personnel. The discovery was made public on Monday by Defense Minister Agustín Rossi.

The documents include 200 original meeting minutes of the military Junta, spanning the period from March 24, 1976, the day of the coup against the government of Isabel Perón (1974-1976), to December 10, 1983, when democracy was restored under Raúl Alfonsín. The files were archived in chronological order and by subject matter inside the basement of the Air Force's main building. "The justice system will decide whether the documents we have found have, besides their historical value, any legal value for the various cases underway in Argentina's legal circuits," said Minister Rossi. "This is the first time we have had access to documentation spanning the entire period [of the military regime]."

The last military dictator, Reynaldo Bignone (1982-1983), had ordered all regime files destroyed in an attempt to conceal its crimes and avoid any subsequent trials for murderers and torturers under the returning democracy. Rossi said that the files evidence "the doctrinaire and ideological backbone" of the dictatorship, and prove that the Junta had a two-tier plan to perpetuate itself into the future: the first reached into the 1990s and the second one, also described as the new republic, was meant to take Junta leaders all the way to the year 2000.

The material unearthed last week includes blacklists of people considered dangerous to the regime, including the writers Julio Cortázar and María Elena Walsh, the actors Norma Aleandro, Héctor Alterio, Federico Luppi and Norman Briski, the journalist Osvaldo Bayer and the musicians Mercedes Sosa, Horacio Guaraní, Víctor Heredia, Osvaldo Pugliese and Marilina Ross.

The last military dictator, Reynaldo Bignone, ordered all regime files destroyed in an attempt to conceal its crimes

There are also around 13 original documents relating to the sale of the newsprint company Papel Prensa, owned by the Graiver family, whose members were arrested and tortured by the military regime. The business was sold in 1976 to the newspapers Clarín, La Nación and La Razón. Rossi said these papers confirm that "the arrest of the Graiver family was directly related to the sale." In 2010, the government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner accused shareholders from all three dailies of acquiring Papel Prensa thanks to the torment inflicted on its original owners; the charge was denied by the accused and the case has not prospered in the courts.

Since the discovery was made 12 Defense Ministry employees have been poring over the documents, classifying them and putting them in a safe place. They will undergo further analysis by the executive over the next six months, to then be passed to the corresponding courts. Between 2006, when impunity laws were revoked by the government of Néstor Kirchner, and early 2013, there have been 91 rulings against regime criminals. Over 2,000 individuals have faced charges in related trials; of these, 370 were found guilty, according to data from the Center for Legal and Social Studies.

A high-profile case began on Monday surrounding the murder of Enrique Angelelli, the bishop of La Rioja (an area in the northwest of the country) in 1976. A man who was committed to his villagers and who fought for their social needs, Angelelli died in a car crash that was initially portrayed as an accident – until a priest who had been in the car with him and survived said that another vehicle had rammed into them head-on.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.