Debt collectors feel public backlash

Techniques used by agencies over small defaults are coming under increasing scrutiny Courts are siding with the consumers against service providers

"We'll call you again." Carlos León heard this threat right before hanging up the phone, knowing that he would get the call again the next day, at exactly the same time. The collector who was demanding payment of a 23-euro debt called him every day at 9am for two whole months.

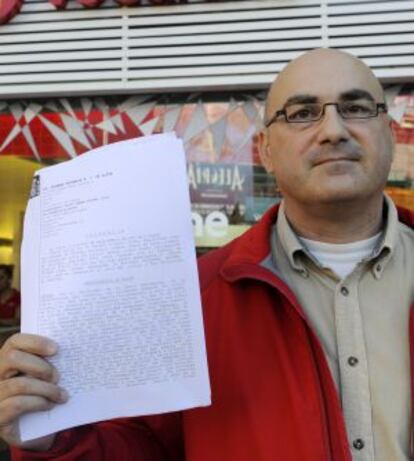

Now, a judge has ruled that León was "intimidated in a constant manner" by the collecting company Konecta; the telephone company that hired its services, Vodafone, now has to pay León 900 euros in damages. The victorious plaintiff has already donated this money to the consumer association that supported him in the case. "I don't care about the money, this was a symbolic thing," he says triumphantly, waving the court ruling in his hand.

This is not a typical case, however. Many people in arrears have received similar calls, sometimes due to discrepancies with a utility bill, but few have ever turned to the courts to denounce the harassment.

Pablo Camacho is very familiar with these practices. A lawyer by trade, he worked for four months at El Cobrador del Frac, Spain's most famous collection agency (so named because collectors used to show up at the debtor's home dressed in a "frac," a tailcoat and top hat). Then, sick of what he considered the firm's "immoral" practices, in 2002 he and two other partners founded a debtor defense agency called El Defensor del Moroso.

A judge has ruled that León was "intimidated in a constant manner"

The genesis for Carlos León's conflict with Vodafone was a change in his internet modem; he says he was told it was part of a free service, yet the company tried to charge him for it. When he sent back the bill, he automatically joined the list of company debtors; this list was handed over to one of the agencies that collect money for the telecom giant. Vodafone defends itself by claiming that it sets down a few rules, such as "calling at normal hours and never more than once a day."

Antonio Vargas, a lawyer from Zaragoza, was also targeted by one of these collection agencies, but his legal knowledge helped him deal with the situation. A company representing the telecom giant Movistar was pursuing payment of a bill that he was in disagreement with. He decided to take action against them. "I knew I had to prove the [harassing] phone calls through a call record, but I can see how any other citizen might not know what to do," he explains. Employees at Credit and Risk Solutions got in touch with him up to 55 times between April and September 2009, according to the Provincial Court of Zaragoza, which ruled in his favor. Even today, Vargas still remembers the impertinent tone of the caller, who would ring every day without fail at 8am, even on holidays.

The most effective solution, explains Camacho, is filing a complaint with the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD) regarding the irregular use of information about the debtor. Telephone companies and lenders are the worst culprits. An AEPD spokesman said that Banco Cetelem and Cofidis, the consumer loan company, accumulate dozens of customer complaints. The bank refused to comment, while Cofidis said that every time it turns to the courts, it wins its cases.

The details of each story change, but the process is nearly always the same. Camacho keeps getting phone calls from people who want the harassment to stop. He says he has had around 600 clients in the 11 years he's been in business. The three partners work out on the street or out of their own homes after their office was burnt down twice, explains Camacho, who was once condemned for slander against his former employer. "Collection agencies are growing like mushrooms, because it is cheaper to resort to them than to the courts, or else because the debt cannot be justified," he says.

Camacho also points out that debt collection has not yet been regulated in Spain, making this one of the few European countries without specific legislation on the issue. In 2009, the ruling coalition in Catalonia, CiU, proposed setting down some rules, and the initiative was unanimously approved, yet it was never put into practice. José María de Gregorio, manager of the Association of Debt Collection Agencies (Angeco), says that its 49 members, who handled around 90 billion euros worth of debt in 2012, have been fighting for regulation for years. "The industry does not have a good image, and the harassment rulings do not help. Some are using highly suspicious practices, but this is not the norm," he says.

One of the cases being investigated by the Spanish Data Protection Agency involves El Cobrador del Frac. One of its agents was sent out to a debtor's house and found that he was not home. "He's not in, I'm leaving a card," he told his supervisor, according to the records of the case. Then this agent did the same thing at the debtor's mother's house. The card hanging from the mailbox had the following message on it: "Debtor, pay up or everyone will find out about you." Asked about it, Manuel Merino, director of the legal department at the collection agency, declines to provide any details and notes that "there is no law regulating good practices," and that they are working "within the legal framework."

But Pedro (an assumed name) disagrees. This Madrid resident is feeling harassed by a small supplier who has not yet been paid. Pedro shut down his two construction businesses two years ago after getting into debt, and to this day he continues to pay back what he owes. But some of his creditors got tired of waiting and decided to turn to a collection agency called El Buda del Moroso. "They're making my life impossible; they call my parents and my in-laws at all hours of the day and night," he claims. This particular collection agency has been sanctioned on several occasions for the same sort of harassment that Pedro is complaining about. This newspaper unsuccessfully tried to reach the company for comment.

Vodafone defends itself by claiming that it sets down a few rules

Telephone collectors found a tough customer in Rubén Sánchez, who happens to be the spokesman for Facua, a major consumer defense association. In fact, he took it like a joke. "There's a lot of fear involved; people don't know where to file a complaint and they find this impertinent person calling them at all hours of the day," he says.

Six years ago, Sánchez broke his minimum-term contract with a telephone company because they raised his rates, and they asked him for 100 euros as a penalty fee. He refused to pay. He received two calls about it, and that was it. Then suddenly, this year the calls returned - first on a daily basis, then every Friday. Sánchez recorded one of these calls and uploaded it online to report the case. Following his personal experience, Facua launched a campaign that has been dubbed #yonosoymoroso (#iamnotadebtor) to help people and offer them the forms they need to fill and file with the Spanish Data Protection Agency.

"They are trying to break you down, but nobody has the right to disturb people's peace like that," says Carlos León, who now sleeps easy knowing that the phone will not be ringing at 9am again.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.