Welcome to the Barcelona fight club

A scrap metal dealer is training young men to compete in brutal no-holds-barred bouts

Juanito walks into the gym at 11am. His rucksack is slung over one shoulder and, under his clothes, you can sense his snakelike body — sinewy, hard and elastic.

“What I put up with, Javi... It was a miracle I didn’t get stabbed,” he says.

Javi listens sat atop an exercise bike.

“Whoever attacked you did so because they don’t know any other language, they’re uncultured,” he replies.

Javier García Roche, Javi, is 32 years old. Juanito is 22. Javi weighs 80 kilos. Juanito barely reaches 70. Javi is a boxer, scrap metal dealer, reformed rogue and dog breeder who loves his mom and his wife. Juan is a kid who spent three years inside for almost killing a guy by stabbing him 16 times.

They are in a rather exceptional gym on the boundary between Barcelona and the municipality of Sant Adrià del Besòs, and Juan is telling Javi about his difficult weekend working on the door of a flamenco nightclub. If anyone passed by the gym, they would only see a metal garage door. Inside there is a ring, punch bags, a kind of cage, a locker room... and Pollo Ramírez, an ex-boxer who right now is training five people as hip-hop plays in the background.

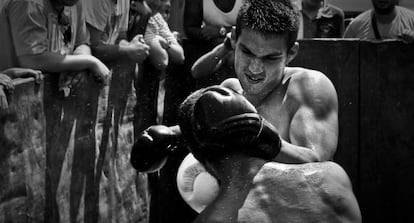

For the last three years Javi has been organizing fights. In them his “kids” — youngsters from the poorer outlying neighborhoods of Barcelona — scrap it out in exchange for “50 or 100 euros.” There are no rules in these fights: the boxers hit each other until one of them surrenders. “Boxing punches, without protection, but with gloves. The one who wins gets paid; the one who loses fighting honorably also gets paid,” Javi notes.

Juanito is one of these kids. He comes to Javi’s gym to train, but also to talk about his life. One day via the Chatarras Palace (Palace Junk Yard) Facebook page he saw that they were organizing fights in a junk yard. “I went, in 20 seconds, I beat the other guy and Javi gave me 120 euros,” Juan explains. After that he became one of Javi’s kids: he trains to fight and win a bit of money.

Javi’s fights are tough. Now he organizes them in the gym to avoid problems, but up until two months ago they were held in his junk yard. “For fun,” he says, he started organizing fights between his workers until one of them, Alexis, emerged as the undisputed champion. “I paid him 200 or 300 euros for the fights,” he says. They were recorded and uploaded onto the internet. Later word spread that Javi was paying and “outside people” signed up to the “junk yard fight.” Every Saturday night the yard turned into a ring where two trainees duked it out for the enjoyment of those present.

Until, that is, Alexis reported Javi. “He says that I was threatening to lay people off to get them to fight,” Javi says. Alexis left his job, and according to Javi, is now in Paraguay. EL PAÍS has tried to locate him but without success.

The fact that two adults decide to hit each other, without anyone forcing them, does not constitute a crime, say police sources. It is another thing, however, if the fights involve animals or there is illegal betting, which Javi denies goes on. Neither can children under 14 attend unless they are accompanied by their parents.

Javi says he identifies with the kids he trains. “He is like the older brother I never had,” says Juan, who suddenly starts talking about his past mistakes. Raised by his mother, he is the son of Juan “El Loco,” a robber who spent 20 years in prison.

The one who wins gets paid; the one who loses honorably also gets paid”

Javi, like Juan and Juan’s father, has also been inside. When he was 16 he belonged to a gang. “We got into fights with other kids. Later we took pills and stole to buy drugs. We wanted to instill fear in the others,” he recalls. Until one day he got into a “big” fight and was arrested, spending “six months in one place and six months in another.” His police record lists two, now deleted, prior offenses, and over 40 identities. Javi talks openly about the fact that he has trafficked drugs in the past and now lives a much better life as a scrap metal merchant. “They did me a favor when they put me in prison. I saw that this was not my place,” he says. And a few years later, when he was about to return to the drug trade, he stopped: “I saw the danger.”

From his experiences as a professional boxer, he had learned that the “more boxing, the less fighting in the street.” Many of his kids, such as “El Bengala,” 19, feel the same. “I have problems on the street, but when I train and fight I let it all out.”

It’s Thursday. There is a fight in the gym — for those who want to, Javi always reminds them. Juan climbs up to the cage, which is the new ring, where Carlos, a Cuban almost twice his size, is waiting. The fight doesn’t last long. Carlos gives him a kick in the neck and Juan totters. He wants to go on, but Javi stops the fight. The session is over. Six kids have fought and Javi has paid out 600 euros. These are his fights and this is his fight club, the Sant Adrià junk yard palace.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.