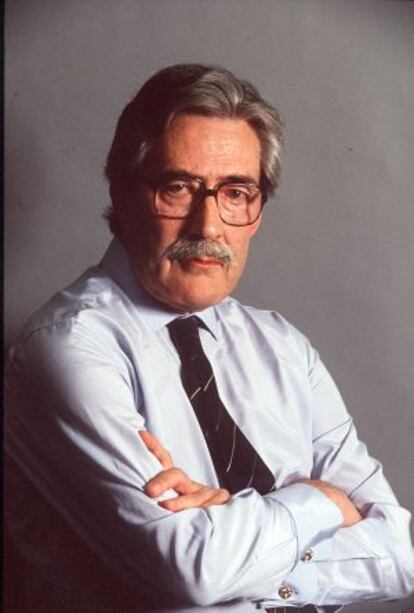

Jesús de la Serna: “el maestro”

The journalist who inspired generations of reporters dies at age 87

To thousands of those of us who learned from him over the years he was simply maestro, although rarely to his face: he hated the term, and it was one of the few truths he couldn't tolerate.

For Jesús de la Serna, who died early on Thursday morning at the age of 87, his readers were all that mattered, and it was to them that he dedicated his efforts during a brilliant career that spanned seven decades.

Rigorous, bordering on austere, he believed that a journalist's only aspiration should be to be read. De la Serna dedicated his life to this profession in the belief that he was not here to impress, but to report reality and to make sure that others did so as well.

He never sought the limelight, and from the wings helped the careers of many of Spain's best-known journalists.

Born in Cantabria, De la Serna was the fifth of nine children born into an illustrious family: his father Víctor de la Serna was a well-known journalist and his grandmother the writer Concha Espina. He died in Madrid after lengthy illness, and was due to be buried on Friday in the village of El Espinar, around 80 kilometers northwest of the capital.

I am not me; I am a large number of people that have worked with me over the years ”

His lifetime in journalism was recognized in May when he was awarded the Ortega y Gasset Prize, which was handed over to him by EL PAÍS's three former editors: Juan Luis Cebrián, who had worked with him during De la Serna's time as editor of the newspaper Informaciones , and who brought him to EL PAÍS in 1979; Joaquín Estefanía, who worked alongside him at the paper's journalism school; and Jesús Ceberio; as well as Javier Moreno, the current editor, a former pupil like so many others.

Summing up his experiences on receiving the lifetime achievement award, Jesús de la Serna told his former colleagues: "I am not me, I am a large number of people that have worked with me over the years and from whom I have learned much, from the biggest names in the business to the least-well known. I am become part of them. This is, above all, a team game."

He may have understood journalism as a team game, but it was one that he believed needed a special kind of leadership. He once told Cebrián: "Remember that the captain eats alone in his cabin."

He was an elegant man whose ability to lead others was always based on respect. He was a quiet man, calm at all times, and able to focus his skills on the task at hand and to bring out the best in those around him. He knew what he was doing at all times, and retained a remarkable capacity to be able to appreciate what was going on around him.

He believed that a journalist’s only aspiration should be to be read

Yet at the same time, he was a very approachable man. He was, if you like, a senior officer who had rejoined the ranks: he was respected by his contemporaries, and admired by the younger generation - not that he looked for either; it was simply that there was something noble about him, a rare quality in this profession. He was amiable and elegant at the same time; a fundamentally good person. During the brief hours his body lay in state at a Madrid funeral home watched over by his wife, Pura Ramos, another journalist, along with his eight children, one of whom, Diego, who also works in the trade, hundreds of colleagues from the profession came to pay their respects: men and women who had worked with him at Pueblo , Informaciones and EL PAÍS, as well as others from a range of media outlets.

They represented different generations of journalists; some had worked with him or been under his direction; others were former students from the journalism school.

First, uncover the truth, and then second, check it.”

In reality, he wrote little. Like most of the great journalists of his generation, he saw his job as leading, often behind the scenes, and was happy to be immersed in proof reading, fact checking, and subediting. He never shouted, never insulted, and always put the needs of the job first.

Once retired, and in the position of EL PAÍS's readers' ombudsman, he wrote more, discussing the key issues of the profession - one of which, he always argued, was the ability to retain one's doubts, to always question - and to point out again and again that journalists must be ready to look at their work objectively, to be able to criticize themselves, and of course to accept criticism.

And time and again, he would remind us of the need to always balance what one source has said with another.

He was, as said, a quiet man, but that calmness could be misleading: he lived by a powerful code of ethics, and was driven by a search for the truth. Reluctantly accepting his Ortega y Gasset Prize, he told his audience: "The first and most important thing is to uncover the truth; the second thing is to check and verify it, because one's sources are not always reliable or sure. You have to check, and look for balance, whatever it takes."

He then reminded those assembled of the aphorism popular in US journalism, a call to common sense: "If your mother tells you she loves you, check it."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.