Peru’s 10-year healing process still incomplete

A decade on from the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Ayacucho shows uneven progress

La Hoyada, an esplanade in Ayacucho city, on Peru’s southern mountain range, was a body dump for the local army headquarters in the 1980s. These days, most of this area has been invaded by homes, but there is still room for a cross in memory of all the missing.

Support groups for victims of the violence committed in Peru between 1980 and 2000 are hoping that this space will be officially recognized as a memorial sanctuary. This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which found that the region of Ayacucho had suffered the most from the Shining Path group’s terrorist violence and the impact of counterterrorism.

Now, Ayacuchanos are defending the need to craft a national history that includes the memory of those times of violence, but they find with sadness that the state seems disinclined to deal with the postwar hardship, either symbolically or materially.

“The (Truth Commission’s) report did not have the expected impact,” says Mariano Aronés, an anthropologist and lecturer at San Cristóbal de Huamanga University. “But that doesn’t mean that the issue is never discussed, or that people don’t want to remember; it’s just that it’s being talked about in other forums, such as within the family. In many ways you could say that the trauma is being relived. There is a sense of disappointment among those who did their military service and received nothing in return; there are fathers who raped women and who are now very vigilant of their daughters,” says this scholar who has conducted research on former military personnel and police officers.

Whether we like it ornot, we are a convalescent society"

Aronés, who is himself the son of a policeman who was murdered by Shining Path in 1983, feels that the Commission’s report was not accepted as an institutionally valid document because it assigns blame that nobody is willing to accept. “It assigns responsibilities, pointing at the culprits and using their full names, and in this country of irresponsible people nobody wants to admit to their mistakes.”

“Whether we like it or not, we are a convalescent society. In Ayacucho I keep hearing: ‘How come the State is incapable of looking our way and seeing to our needs?’” adds Aronés, noting that when former President Alan García and President Ollanta Humala were candidates, they both met with victim associations in Ayacucho to offer reparations. But there has been little progress since then.

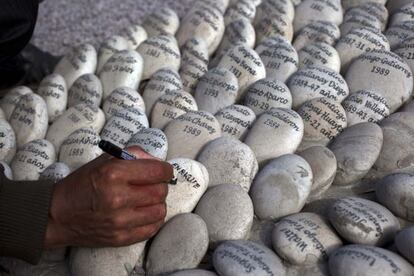

On a positive note, says this scholar, in recent years many corpses have been dug up and returned to their families for proper burial, bringing closure for their loved ones. Relatives can finally say: ‘At last, I can sleep with a clear conscience.’ And that is one way of compensating them for their suffering. According to a report released this week by the Ombudsman’s Office, there are 6,462 burial grounds in the country, while the General Attorney’s Office holds that 15,700 people went missing during the two decades of violence.

The same ombudsman’s report notes that there are still pending issues that the state must resolve, such as the fact that people who were killed or wounded by antiterrorist actions after the year 2000 are not legally eligible for compensation.

Aronés also underscored an unresolved problem: the need for a protocol for the people (including minors) who were recruited by thr Maoist Shining Path and were subsequently rescued in counterterrorism actions.

“A lawyer asked me for an expert anthropologist report on two women of the Ashaninka ethnic group who had been arrested at a Shining Path campsite. One had been abducted by the Path when she was two or three; the other when she was a little older. These women took care of the children, prepared the food, never left the camp, did not know what part of the country they were in, had no surname, and had never seen money,” recalls Aronés, whose report prevented both women from being convicted of terrorism. “They didn’t understand Spanish well, and they had no ideology, since they didn’t even understand.”

Yuber Alarcón, an advisor for the Apoyo para la Paz (Support for Peace) program in Ayacucho, believes that between 2004 and 2005 “the people of Ayacucho and the victims did embrace the (Truth Commission’s) report and they helped disseminate the message. There was a rise in the number of victim associations in the provinces, but since the end of the Alejandro Toledo administration, it has lost relevance and meaning.”

Edilberto Jiménez, an anthropologist and altar-maker from Ayacucho, wrote a book about the massacres at Chungui, a district of Ayacucho that lost 17 percent of its population between 1983 and 1984; 1,384 people were killed or went missing. “Thanks to the vision of the Truth Commission, we know the scope of the dirty war or the violence,” he says.

A 30-year search

Adelina García is the president of the Association of Relatives of Abducted and Missing People of Peru, the country’s largest victim group, founded 30 years ago on September 2. García, a native speaker of Quechua, lost her husband when he was a college student in Ayacucho. Because of the blows she sustained while he was being dragged away, she lost the baby she was carrying.

García feels that the Truth Commission’s main achievement was the Single Registry for Victims of Violence, one of the few recommendations that the State did follow. It is the list of people who are owed some kind of compensation, either financial, symbolic, or health and education-related. There are currently 182,350 names on the list, of which 59 percent are direct victims and the remaining 41 percent are relatives.

The president of this association admits that Commission members were unable to investigate every case of violence because of the short space of time they had to produce their report. “Many hamlets where cars and roads don’t reach were deprived of a chance to provide testimony,” she says.

Adelina García is critical of the fact that while a third of the cases have gone to court, many others are being dismissed or else the guilty parties are being acquitted. “Sometimes there is additional pain for us,” she says, adding that victims don’t get enough money: 3,500 dollars per family, with no regard for the number of family members or whether there was more than one victim in the family.

Meanwhile, the anthropologist Lurgio Gavilán, author of the most revealing book to date on the violent years, Memorias de un soldado desconocido (Memoirs of an unknown soldier), says that despite the passage of time and the cooperation projects by a few non-profits, some poor communities remain as poor now as they were back then. “There are more needs now: the land is getting poorer and they need to buy a TV, a cellphone, and to pay for services that they didn’t use to have.”

And the tools for dealing with the pain in Ayacuchan villages, says Gavilán – who joined Shining Path as a child and became a Franciscan friar as an adult — are often rudimentary. Pure silence is one of the ways in which families handle resentment between neighbors. This resentment sometimes comes to the fore during carnival time, when people have had too much to drink. They also use symbolic rites representing hatred and forgiveness. For instance, the family of a guilty person might present the family of the victim with a bull to seek forgiveness.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.