The never-ending search for beauty

Burgos’s Museum of Human Evolution examines our changing esthetic obsessions

When the Romans conquered Germania two millennia ago, they not only enslaved the population and transported them to work in Italy, they also sheared off the subjugated Huns’ flowing blond locks and sent the hair back home, where stylish Roman ladies had it made into wigs.

Eighteen centuries later, as Romanticism swept through western Europe, setting new standards of beauty that left behind the full figures celebrated during the Renaissance, women were required to appear delicate, and would reduce their weight by consuming little more than vinegar and lemon juice, risking their health in the process.

These are just two examples of mankind’s obsession with appearance featured in La belleza, una busqueda sin fin (Beauty, the never-ending search), an exhibition of over 100 objects that runs until January 12, 2014 at the Museum of the Evolution of Mankind in Burgos.

“Our ideas about what constitutes beauty have changed according to the dominance of different cultures,” says Quionia Herrero, the curator of the exhibition. The show, which has been jointly organized with French cosmetics firm L’Oréal, explores the role that biology plays in our need for beauty, even if culture is what finally determines what we do and do not consider beautiful. “If we ask ourselves the question: why are we programmed to detect beauty, we immediately come up against the classical theories of symmetry, proportion, and genetic inheritance,” says Herrero.

There are theories arguing that beauty is a system of signals to pass on genes”

A perfectly proportioned nautilus conch stands at the entrance to the exhibition, its perfect spiral gradually disappearing into its inner shell, following the aureole formula, fortunately for Pythagoras, the illuminated manuscripts of the medieval period, the Parthenon, the Mona Lisa and the designs of French architect Le Corbusier, but less so for Charles Darwin.

The British naturalist thought that he had studied every aspect of the finches he found in the Galapagos, but there was one bird that resisted categorization. The peacock drove Darwin to distraction with all the colored plumage and complex mating rituals it employed to catch the eyes of females.

Darwin believed that provocation was about laying a trap for predators rather than future partners. In other words, his theory about the struggle for a species’ survival was nullified by courtship rituals. But before throwing in the towel, he decided to include in his Origin of the Species a chapter about sexual selection, which explored the ways in which the male of the species was concerned about looking good in order to attract a female mate. “There are scientific theories arguing that beauty is simply a system of signals to pass on genes,” says Herrero. “The greater a species’ reproductive success, the better its special genetic qualities, for example a strong immune system.”

Less dangerous, but equally superficial, are some of the tools from prehistory. The ax heads made by Homo ergaster included in the exhibition are evidence of early man’s search for beauty: a symmetrical tool made of polished stone, it is of no practical use, despite its appearance.

Australian aboriginal cultures believe an undecorated body is not human

In 2004, a group of potholers exploring the Atapuerca Mountains’ cave network found a mysterious gold artifact dating back to the Bronze Age. Dubbed the Silo Jewel, the bracelet shares a display case with a Roman gold diadem from the 1st century BC, along with Egyptian necklaces from the collection of Spanish Egyptologist and collector Rafel Pagés. “Civilizations such as the Greek and Roman did not consider a person to be beautiful unless they applied lotions, perfumes, and used makeup, which they believed also transmitted magical powers to the wearer,” says Herrero. “In prehistory, and in some Australian aboriginal cultures, an undecorated body is not considered human.”

Humankind’s pursuit of beauty, and with it social acceptance, over the centuries has also inflicted pain and suffering on women. Within the 400 square meters of the exhibition there is no shortage of objects exemplifying the dictates of beauty: the practice of binding women’s feet in China; cranial deformations carried out on babies in Central America; the rings placed round the necks of Karen women in Thailand; the black teeth that are the result of the Japanese technique of ohaguro; and the restrictions imposed by the wearing of corsets in pre-revolutionary France. “They mix the need to meet the requirements of beauty and social distinction, because however hard the lower orders have tried to imitate elites, there have always been limits,” says Herrero, pointing out that few people in early 19th-century France could have afforded custom-made perfumes, as Napoleon did.

The perfumer Jean-Marie Farina created a special cologne for the French leader that came in a long, thin bottle that he could slip down his boot, allowing him to freshen up without having to dismount from his horse. Before the French Revolution and the industrial age brought an end to their vanities, the European courts of the 17th and 18th centuries were filled with women who sought social distinction by dressing their hair upward into towering pompadours and coating their faces with thick layers of makeup.

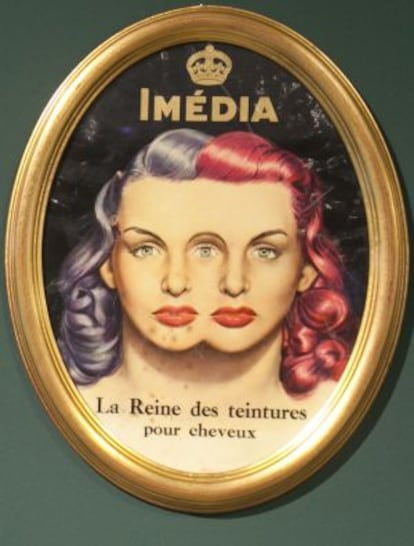

The exhibition also includes examples of makeup from the distant past, such as mineral ochre, kohl, henna, mercury, rice and wheat flour, as well as the first synthetic products developed toward the end of the 19th century.

Lemon juice and incense were once used to disguise body odor

Lemon juice and incense were the key ingredients in the first lotions developed to counter body odor, liberally applied. In later years, zinc chloride would be used.

By the late 20th century and the beginning of the new millennium, we find ourselves bombarded from all sides by new ideas of beauty. We haven’t just been subjected to new ideas associating being fat with laziness and thinness with success; at the same time the Church has also had to cede territory. “Christianity is about the purity of the body, the most beautiful object, and the means by which we measure all,” says Herrero. “That said, piercings and tattoos, considered something exotic, associated with African cultures that practice scarring and use pigments on the body, have become part of Western culture.”

“Technical advances haven’t just helped establish this ideal of beauty, in recent years they have also multiplied the number of biotechnology and medical patents relating to cosmetics,” she says, standing next to a display case in which L’Oréal has placed petri dishes containing human tissue. Not only do the company’s laboratories use them to test products, but they also allow scientists to research new techniques for skin grafting.

“Our eternal desire to discover the secret of immortality will probably never die away,” says Herrero.

Perfume maker Jean-Marie Farina created a special cologne for Napoleon

“I wouldn’t like to hazard a guess as to what the new ideals of beauty will be, but the future debate will be between the biological trend towards eugenics, which is already being practiced and doesn’t have to be limited to choosing a baby’s sex, and applying technology to the body.”

In which case, will we all end up as cyborgs? “Aside from implants, we may well reach a point where robots take over the tasks we have until now assigned to our memory, along with other jobs.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.