From trash to museum treasure

The booming fascination for work by unknown photographers is dividing experts

In his famous essay Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes noted that every photograph encloses a death - "[it] mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially" - and an almost religious impulse: photography is a kind of "resurrection," he said. The great French thinker went even further by saying that photography is the means by which our age comes to terms with death.

His comments perhaps go some way to explaining the growing fascination for anonymous and popular photography - a trend that is helping proliferate the rescue, sometimes straight from the garbage, of the work of many unknown photographers. "More than any other form, popular photography puts us in contact with the past and with memory," historian Publio López Mondéjar points out. "People have grown tired of smug photography, of looking at things they don't understand, and are looking for a story from the photography that hasn't forgotten what photography is - which was and is no more than a simple act of documentation."

They are the stories of people such as Piedad Isla, who spent her life traveling around the mountain towns of Palencia, first on her bicycle, later on a motor scooter, with nothing but her camera. She captured thousands of moments of 1950s and 1960s Spanish life at the same time as she made a living taking passport, wedding and christening photos. "There were laws that prohibited women from doing many things, but none of them said a woman could not be a photographer. So I decided to be one," Isla said in an interview just before her death with La voz de la imagen, a documentary project that collects the testimonies of these photographers.

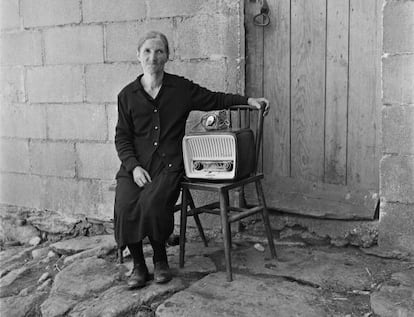

Isla's legacy offers a unique panorama of seamstresses, farmers, shepherds, funerals and fiestas. Just as singular is the work of Galician photographer Virxilio Vieitez, whose current exhibition at the Fundación Telefónica in Madrid attracted 90,000 visitors. Or that of the mysterious Vivian Maier, the nanny who secretly captured images of children, women, old people and the destitute on the streets of New York and Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s. "They are captivating because they are humble photographs, with no pretensions. It is that charm that is coming back now more strongly than ever," says Mondéjar. "I would never swap a Cindy Sherman photograph for one by Vieitez. Sherman is witness only to herself. Which is to say, the opposite of what a photographer should be."

I sincerely believe that no great photographer is unknown"

Some experts, such as Robert Flynn, a US collector and the author of the book Anonymous: Enigmatic Images from Unknown Photographers (2004), say there are thousands of photos out there waiting to be discovered and transmuted from trash to treasure.

Others, however, believe there can be no masterpieces without authorship credentials and context. Lola Garrido, a photography expert and owner of one of Spain's best photography collections, thinks the treasure is all an illusion. "We all want to find a gold mine. But I sincerely believe that no great photographer is unknown. The story of Vivian Maier is an isolated case [...] But the majority of discoveries come to nothing."

Jorge Ribalta, who curated the exhibition A Hard, Merciless Light. The Worker Photography Movement, 1926-1939 at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid in 2011, says recovering the archives of dead photographers also raises an insurmountable problem. "An author is someone who selects and interprets the negatives in their archive. Vieitez is not an author; it is the operation, at least arguably, of a curator or historian, who interprets his work. It seems stupid, but it isn't, because you can build a masterpiece from any archive of negatives. From a historiographical point of view, it presents a problem of rigor. The role of an author is to make his own selection and if he doesn't do it, no one else can."

For Ribalta, recuperating these figures is an act of fetishism that rather than fulfilling modernity's promise of democratizing creation, "paradoxically" achieves the opposite. "The history of photography is not the history of images, but rather of the public life of those images in their time," he concludes.

The photographer Walker Evans once said that good photography is and should be literature, a view to which López Mondéjar subscribes. "It's something the experts have forgotten. Virxilio Vieitez's photograph of an old woman posing with her radio is not a coincidence; it is a story: that of a mother who sends a photograph to her son, next to the new home appliance. As simple as that. We just want to know - we need to, faced with so much damage - the truth about our parents and grandparents' time. And photography, though it can lie, is the least deceiving."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.