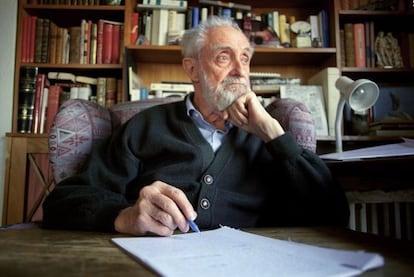

José Luis Sampedro, the voice of a new generation

Writer and economist who inspired Spanish protest movement dies at 96

The clear voice of José Luis Sampedro — a writer, humanist and economist who closed the generational gap to become a standard-bearer for Spain’s disaffected youth — died out last Sunday. The 96-year-old intellectual passed away in his Madrid home the way he wanted to: quietly, just like he lived his life.

He wanted to go “in a simple manner, without publicity,” said his widow Olga Lucas, whom Sampedro married in 2003 and thanks to whom, the writer used to say ironically, he was able to “face death with great serenity; she makes my moribundity quite satisfactory.”

Sampedro, his widow recalls, “felt panic at the media circus surrounding the death of famous people.” That is why he left it in writing that his death should only be announced after his cremation. And so it was.

Sampedro was one of the intellectual and moral role models for the “Indignados” protest movement, a fact that made him enormously popular in later years. It is no coincidence that it was him who introduced Spaniards to another rebel in his nineties, Stéphane Hessel, author of the unexpectedly popular booklet Time for Outrage!

“There are two types of economists: those who work to make the rich even richer, and those of us who work to make the poor less poor,” Sampedro used to say. As a university professor, his students included future economy ministers such as Miguel Boyer, Carlos Solchaga, Pedro Solbes and Elena Salgado. Yet he never traded in the pulse of the street for the influence of the halls of power. A senator by royal appointment since 1977, Sampedro had an apartment in Mijas Costa (Málaga), where he liked to spend part of the winter, and on the wall he had a plaque with the inscription: “Avenue of the Republic.”

I wanted to be a Jesuit at age nine and an anarchist at age 19"

Yet Sampedro’s popularity is not a recent event. It grew phenomenally in 1985, when he published his novel La sonrisa etrusca. Through it, thousands of readers discovered “a humble, wandering man.” Sampedro used this phrase by the turn-of-the-century novelist Pío Baroja to define himself when he was admitted into the Spanish Royal Academy in June 1991.

Although he was born in Barcelona on February 1, 1917, he lived in the Moroccan city of Tangier until the age of 13. In 1936, the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War caught him working in Santander, and he was mobilized by the Republican army. A year later he deserted and went over to the Francoist side, which he considered more in tune with his own beliefs. Finally, the atrocities of war pushed him away from both sides.

“I wanted to be a Jesuit at age nine and an anarchist at age 19," he used to say. Born into a well-off family, he was a diligent student who passed national examinations to be a customs official. Meanwhile, his war experience provided inspiration for his novel La sombra de los días, which he wrote in 1945 but which was not published until the 1990s.

“I was a militiaman until August 1937, when the nacionales took Santander and took me as well. I became a national soldier until the end, which turned out to be worse than the beginning. When ‘my guys,’ as I thought of them, started executing people, I realized that the winners of the war were not ‘my guys’ at all,” he wrote in Escribir es vivir, a collection of transcriptions of lectures he gave on the subject of his work in 2003.

Besides novels and essays, Sampedro also wrote about economic issues throughout his life, including the most recent El mercado y la globalización (The market and globalization), published in 2002. This math type/poetry type duality was always a hallmark of Sampedro’s personality – sometimes extravagantly so. During the postwar years he combined an advisory position at the Trade Ministry with a side job as a playwright for theatrical revues, using a pseudonym.

His public debut as a novelist came in 1951 with Congreso en Estocolmo. He was 34 years old and the story was based on a trip he had made to the Swedish capital two years earlier for a gathering of economists. Years later, Sampedro still reminisced about the abysmal contrast between Spain and Sweden at the time.

Sampedro was a humanist who was only isolated from reality (and just partly) after becoming deaf in later years. Olga Lucas, his widow, told Europa Press that that the writer had accepted death as a natural event, “inasmuch as he did not really feel like dying.”

“He used to say that he was afraid of failing, of not being able to die with dignity, but he was not afraid of death itself,” she said.

He was peculiar to the end. “He told us he wanted to drink a Campari, so we made him a Campari with crushed ice,” continued Lucas. "He looked at me and said: ‘I’m starting to feel better. Many thanks to everyone.’ Then he fell asleep and a while later he died.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.