The judge who doesn’t play Cluedo

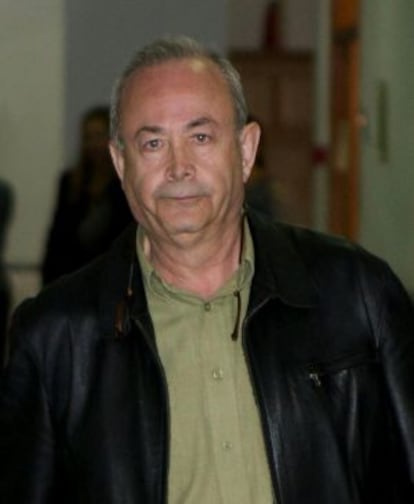

José Castro Aragón is a meticulous, respected magistrate devoted to his work of weeding out corruption. Despite his profile, he blushes at public applause

In the chambers of High Court Judge José Castro — “call me Pepe,” he always tells people he knows — there was a thesis behind Wednesday’s court summons issued to Princess Cristina, the youngest daughter of King Juan Carlos I. “It is not sufficient to harbor suspicions or imagine conspiracies. Clues and intuition are of no use in a lawsuit. A judge is not Agatha Christie.”

The day before the judge named Princess Cristina as an official suspect in the investigation into the alleged embezzlement of public funds through the Nóos Institute run by her husband, Iñaki Urdangarin, Castro slipped a cryptic line into his court records: “On the investigating judge’s table is the drawn up request [...] regarding the declaration of a certain person.”

That certain person was revealed the following morning to be citizen Cristina Federica Victoria Antonia de la Santísima Trinidad de Borbón y Grecia.

The magistrate, who does not make public comments or allow portraits of his persona to be made, did not want journalists and chat shows to mark the calendar of the lawsuit or set the date for the news story of the year. He is known to be good-natured and supportive, always prepared to fill in as on-duty judge for his colleagues.

Castro is also a lone wolf. He is not a member of any association of judges and does not participate in any sort of professional events or activism. When he has found himself on the receiving end of accusations from far-right groups or has been called to answer to the General Council of the Judiciary legal watchdog — over the alleged leak of a court report or for traveling to Barcelona or Madrid to conduct interviews — Castro has always won through and earned the backing of his colleagues.

He has proved impervious to smear campaigns by his targets and the attentions of a private detective hired by a powerful indictee.

A meticulous magistrate, he inspires the respect of public figures and common criminals alike. In fast-track cases he seeks to find common ground for agreement and applies an almost paternal manner when eliciting the simple narration of events.

Judge Castro is 67 and lives in a small semi-detached by the sea in Palma de Mallorca. He is separated and has three sons, all legal professionals. José Castro Aragón blushes when applauded in the street by a passer-by. He did not enjoy the cheers of the public when, in February last year, he was to interrogate Urdangarin for the first time. For that encounter, he drew up 500 questions in 20 hours.

Castro is a lone wolf. He is not a member of any association

A veteran public prosecutor in Palma defines Castro as “the law-abiding judge.” There are those who joke that when he retires he should open a simple bar, Bar Pepe or Casa Pepe, where can apply his organizational skills.

Judge Castro leads his court employees and the police in his investigations, attending property searches in person. He has worked within the prison system, as a judicial secretary, a tribunal judge and, for the past 23 years, as an examining magistrate.

His travails have taken him back and forth across the country. He has eschewed promotion to higher courts and internal progression.

After a recent cycling accident, he spent a few days in hospital, fewer than he was entitled to. Those people who visited him during his short recuperation period say he took the case he was working on with him to his hospital bed.

At the beginning of the 1990s he led the investigation into the first major corruption scandal to affect the Popular Party in the Balearic Islands, the Calvià case, in which the complainant recorded the suspects as they were offering him bribes. Castro sent a commission agent and a PP politician to jail. The Palma High Court convicted on charges of bribery and the Supreme Court validated the sentence and the format of a new penal crime.

Castro’s briefs result in sentences. In the Palma Arena case, in 2012, Castro’s probe led to the sentencing of the former regional premier of the Balearics and an ex-PP government minister, Jaume Matas.

The Nóos case is an offshoot of Palma Arena. Balearics anti-corruption investigator Pedro Horrach, leading the Palma Arena probe, found indications that Matas’ administration contracted Nóos to organize sports tourism events for vastly inflated fees.

The investigation is focusing on two contracts Urdangarin's Nóos Institute received from the Balearic Islands government, worth 2.3 million euros, and four from the Valencia regional government, worth 3.7 million euros between 2004 and 2006.

Horrach on Wednesday announced he was to launch an appeal against Castro’s decision to name Cristina as a suspect.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.