"When I die, I don't want anybody to cry"

Bebo Valdés had the gift: he didn't just play the piano, he caressed it

"When I die, I don't want anybody to cry. I want you to throw a party and dance and get drunk."

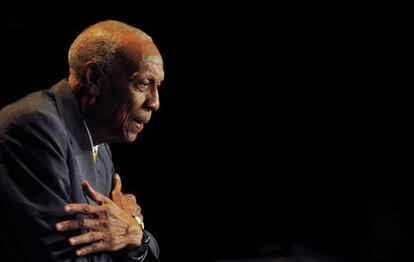

Before his death last Friday at age 94, I heard him say this many times. Bebo was a child. One look at his playful eyes and wide, infectious smile and you knew it. He was also a modest man, who awarded more importance to others than to himself. He was not ambitious, although he was proud - especially of his son Chucho, and of a job well done. He was an impeccable professional who always arrived on time, always looked elegant, and was invariably kind to everyone.

In the lovely documentary by Carlos Carcas, Old Man Bebo, you see Pío Leyva, one of many people whom Bebo helped out throughout his life, exclaim: "Bebo Valdés..." then his voice trails off, his eyes well up with tears, and he adds in a sigh that seems to come straight out of his soul: "What a good person!"

Very likely Bebo cared more about this than about anything else, including music, his own work and his career - things that he did not hesitate to sacrifice in the early 1960s to make sure his new family wanted for nothing. He was not a religious man, although he believed that the same single god was behind all religions.

I could go to Cuba with Castro in the presidency. As long as Cubans elected him"

Bebo did not like to talk about politics, but there was hardly an interview in which he was not asked about Cuba or Castro. Somebody once told him: "So you never plan to return to Cuba as long as Castro is still alive, then." Bebo, looking surprised, replied: "Why do you say that? Yes, I could return to Cuba with a living Castro, absolutely. Even with Castro in the presidency. That is, as long as he is there because Cubans have elected him." Is it possible to display greater moral rectitude?

I once convinced him to record a solo piano album. Those were wonderful days, just the two of us spending time in rehearsal and recording studios in Madrid, with no concerns other than music. Ned Sublette (author of Cuba and its music) came up to me in New York one day and said. "I want you to know that Bebo is the best Cuban music album ever recorded, anytime, anyplace."

I think that this album contains both Bebo's and Cuba's soul - bare, without ornaments. It was the last thing that [exiled Cuban writer Guillermo] Cabrera Infante listened to before dying in a London hospital. Tears rolled down his eyes as he heard it, and I thought to myself, 'He has died in Cuba.' I told Bebo about it and we dedicated the album to him.

Guillermo died in London. Bebo died in Stockholm. What kind of government makes its best musician and its best writer die so far away from home?

The last time I visited him in his home in Benalmádena (Málaga), he suddenly said to me: "You know? I'd like to go to Cuba." I couldn't believe it. I had never heard that sentence from him. "I think that's fine, Bebo. No Castro can stop you from doing whatever you want. But it's a very long trip, and I'm not sure you're up to it." Yet I could imagine him hugging his brother Arsenio, kissing his children, Miriam, Mayra, Raúl, his grandchildren... "I would like to see my parents," he added. And then I thought I knew what was going on: his mind was failing him, like it had on so many occasions in recent times. But actually, his mind was quite clear: "I want to visit their grave."

I met him when I offered him a role in [Latin jazz documentary] Calle 54 and it was "love at first sight." Between 2000 and 2010 we made eight albums and four movies together. We traveled throughout Spain, the US and Brazil, and talked for hours, days, months, from dawn until dusk. All of those moments are precious to me. His humanity, kindness, joy and innocence were truly disarming.

When he played, his hands gave you the feeling that the mystery lay there: they were strong and delicate, like his music. Bebo did not play the piano, he caressed it. His sense of time was magical, and he could leave you suspended between two notes. He was in possession of "the secret," something that goes beyond technique or virtuosity. Just one note of his could transport you to another continent, another era. Bebo was the real thing.

I had the tremendously good fortune of meeting Bebo Valdés and the privilege of being his friend, and for that, I thank life once again.

Far from Paradise

Bebo Valdés found himself in the conundrum of so many Cuban musicians. Cuba is a land fabulously fertile in rhythms and melodies, yet its artists are often obliged to emigrate in the aftermath of political commotion, or simply out of the need to make a decent living, which is usually impossible in a tight little market such as that of Cuba.

Thus we see careers as intermittent, and as wonderful, as that of Bebo. A star of the highest order in the world of Havana music in the sparkling 1940s and 1950s, he functioned equally as pianist, composer, arranger and band leader. A regular at the Tropicana, it was Bebo they called on when Nat King Cole showed up in Havana to make a record in Spanish.

Like so many other instrumentalists of his generation, he was fascinated by the possibilities of jazz, developing his own style of jam session. He also tried his hand at the mambo that was then being popularized by Pérez Prado, with his batanga. But - I have to insist - you must not overlook the exuberant recordings of popular vocal artists of those golden years, which bear his style like a fingerprint.

Then came the revolution, which practically overnight cleared out the high-rollers and the tourists, and closed down all the nightclubs and other haunts of vice. It was soon followed by the first wave of exile. Bebo left his family in Havana and went off to make a living in Mexico, with the splendid Roland Laverie. Lengthy stays in the United States and Spain followed. He seemed to be innocent of any sort of prima-donna conceit: accompanying trivial singers of light music just as brilliantly as he supported famous voices of the bolero such as Lucho Gatica. There was always work for someone of his abilities, but few opportunities for creative self-expression. All the more so when the vicissitudes of the heart took him to Stockholm, where he soldiered on as a pianist in a hotel, ever smiling, ever ready to please customers with requests.

But Bebo was not lost in space. His name may have been wiped from the books of the Castro regime, but in the wandering world of Cuban musicians exiled in Europe or America, people in the know always kept tabs on his whereabouts. In the early 1990s, when the German recording label Messidor went into Afro-Cuban jazz, Paquito D'Rivera easily convinced him to star in the album Bebo Rides Again, which was prepared and recorded in a matter of a few days. You would never guess this, to judge from the fine quality of the arrangements, the energy of the compositions and the delight with which the exiles, and others who had stayed at home in Cuba, once again played together.

The Messidor project came to nothing, but then Fernando Trueba and Nat Chediak appeared and put him to work on records and documentaries that exhibited the range of his resources. The public fell in love with his aplomb, with the long skeletal fingers that illuminated the images of Calle 54 (2000) and El milagro de Candeal (2004). His life story inspired Chico y Rita (2010), the animated-cartoon film by Trueba and Mariscal. But reality was even more amazing than any movie script: an octogenarian Bebo became a world star thanks to his exquisite work in Lágrimas negras (2002), his collaboration with the flamenco cantaor Diego El Cigala. Amid the frenzy of tours, Bebo gave evidence of his high human quality. And yes, he once again crossed paths on the stage with the most famous of his sons, also a pianist: Chucho Valdés. The lives led by Cubans, as we all know, tend to have twists and turns.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.