The murderer who's working for the Spanish Civil Guard

Hellín Moro was jailed for killing a 19-year-old woman his far-right group believed was a terrorist

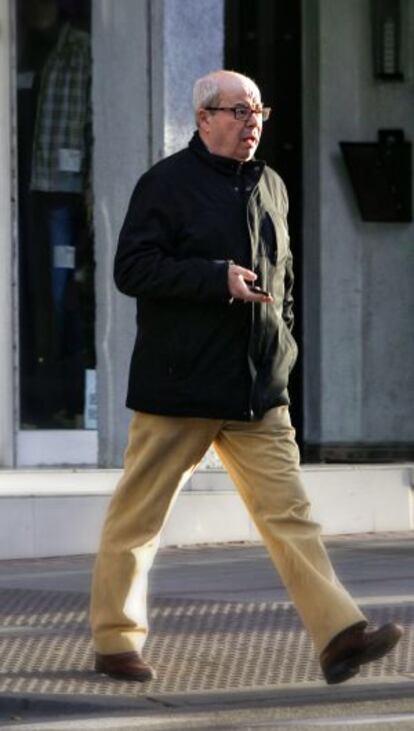

Are you Emilio Hellín Moro?"

- I am Luis Enrique Hellín...

- Excuse me, but aren't you Emilio Hellín, the man who murdered Yolanda González, the 19-year-old Socialist Party activist, in 1980?

- No... Emilio Hellín died three or four years ago... We're related.

- I didn't know that he had a brother called Luis Enrique.

- It's a long story: we have the same mother but different fathers...

- You really are alike! And both of you computer experts. Do you know how I could contact his family?

- I can't help you.

- Where are you from? Can you show me your identity card to prove that you are not Emilio Hellín?

At this point, the conversation comes to an abrupt end.

In 1980, Emilio Hellín, then aged 33, belonged to Fuerza Nueva (New Force), a fascist party dating back to the 1960s, and was also linked to another shady far-right group called the Spanish Basque Battalion, which had been set up two years earlier to fight for a "great, free, and unique Spain." They killed 12 alleged members of ETA in the process. In 1982, along with another man, he was convicted of the murder of Socialist Party activist Yolanda González - who had no links to ETA - and was sentenced to 43 years in jail.

The man who today says he is Luis Enrique Hellín Moro, is tall, well built, and appears to be in his mid-sixties. He is dressed casually, wearing a check shirt and corduroy trousers, and is composed, showing no sign of nervousness during the conversation. The meeting takes place in the offices of his company, New Technology Forensics, in a quiet suburb of Madrid. The three-story premises is untidy, with old computers and cellphones scattered on desks and piled up on shelves.

There is no reference at Madrid's main registry office of the death of Emilio Hellín Moro. The Interior Ministry says that it has not renewed an identity card bearing that name; but it has issued one for Luis Enrique Hellín Moro.

EL PAÍS has been able to confirm that 16 years ago, Emilio Hellín Moro changed his name to Luis Enrique Hellín Moro at the registry office of a tiny village called Torre de Miguel Sesmero, in Badajoz, Extremadura.

Spanish law allows for name changes "if good reason can be given and it does not harm third parties." Hellín began covering up his past as soon as he was released from prison after serving just 14 years of his sentence. He was soon able to return to security work, specializing in IT and telecommunications, providing electronic eavesdropping, as well as combing computers and cellphones.

Since then, EL PAÍS has discovered that Hellín Moro has secured contracts with the country's security forces and is an advisor to the High Court and the Civil Guard, taking part in investigations into terrorism as well as other crimes. He also gives training courses to national and regional police officers, as well as Ministry of Defense personnel, and regularly attends conferences held by the armed forces - all paid for by the Interior Ministry.

Extremists with orders?

During his trial, Hellín Moro said that the order to kidnap, interrogate and then kill Yolanda González was given by David Martínez Loza, a former civil guard, and head of Fuerza Nueva's security. Hellín Moro told police immediately after his arrest that he had been ordered to take all the blame for the killing, and that if he kept silent, he would be compensated further down the line. "The police told me that it wasn't worth implicating anybody else in this," he said. Hellín also said that Fuerza Nueva, which expelled him after the killing, never fulfilled its promise of help.

When asked by prosecutors who gave the order to kill Yolanda González, Hellín Moro not only gave Martínez Loza's name, but also implicated other members of Fuerza Nueva, as well as several police officers. But Ignacio Abad Velázquez, who also participated in the killing, said the whole thing was Hellín Moro's idea. In the event, Martínez Loza was convicted of ordering the kidnapping, but not the murder, of Yolanda González.

"Nobody was interested in getting to the bottom of this, and finding out how many police officers might have been involved in the killing of my sister. The links between Hellín, Fuerza Nueva, and the police were scandalous," says Yolanda González's brother Asier.

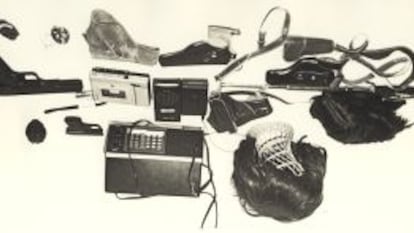

Alfonso Guerra, former deputy leader of the Socialist Party, said at the time that the PET 201 micro-computers found at Hellín Moro's premises were linked by telephone to a computer used by the Civil Guard based in a private house in the wealthy El Viso area in Madrid.

Major Ramón García Jiménez, a former head of the Civil Guard's IT unit within its Criminal Laboratory, describes Hellín as extremely well qualified, and on the cutting edge of IT-related criminal investigation: "He advised us on how to solve cases, how to build them, where to look for evidence. We would ask him for help on how to retrieve information from cellphones. He also helped train officers, an activity I imagine he remains involved in."

Asked if he knew anything about Hellín Moro's past, Major Jiménez replies: "I know nothing about this man's past. All I can say is that he has always performed whatever task we asked of him."

In 2008, Hellín Moro participated in a conference for Civil Guard officers about the use of new technology to fight crime, held at the University Institute of Research in Political Sciences (IUICP). Virginia Galero, the IUICP's current head, says that Hellín Moro was invited to the conference because of his "specialist knowledge."

José Miguel Otero, the organizer of the conference and deputy director of the IUICP, as well as the head of the National Police's forensics unit, says that he does not know Hellín Moro, and does not remember meeting him. "He must have been invited by other members of the institute," he says.

Also attending the conference in 2008 was the High Court judge, Eloy Velasco, as well as Matías Bevilaqua, a computer expert recently arrested by the police for his alleged involvement in a network set up by senior police officers to sell confidential information. Bevilaqua says that Hellín's contribution to the conference was "outstanding" and that Hellín has given several courses to the Civil Guard on removing information from Mac computers, as well as iPhones and iPods. His most recent collaboration with the police was last year, when he was called in to help trace calls made by José Bretón, who is accused of murdering his two children in Seville and disposing of their bodies in the garden of his house.

The murder of Yolanda González in 1980 stunned the nation. She had been born in the Basque town of Deusto into a working-class family. The eldest of three children, she was an outstanding student. At 16, she joined the youth wing of the Socialist Party, and became an active member, distributing leaflets at factory gates and attending meetings.

She moved to Madrid when she was 18 to study electronics at a technical college in the working-class suburb of Vallecas, cleaning houses to make ends meet. "She was a clever person, full of life, and very enthusiastic about everything she was involved in. She was always thinking about how she could help others," says Alejandro Arizcun, her boyfriend at the time of her death, and who is now a university history teacher.

In January 1980, Yolanda took part in a general strike in the education sector, appearing in photographs at the head of student protest marches in Madrid.

Crimes that shocked Spain

The front page of EL PAÍS on February 12, 1980, less than two weeks after González's murder, reported that two members of the Fuerza Nueva far-right group had been behind the student activist's killing and that they had been arrested by the police while in possession of a cache of weapons and explosives. Just days before González's murder the same organization had shot dead a young man named Vicente Cuervo in Madrid's Vallecas district.

On the evening of February 1, 1980, Hellín Moro and Ignacio Abad Velázquez knocked at the door of González's home. She was not in, so they waited in the street until midnight, by which time she had returned. Believing she was involved with ETA, their intention was to kidnap and question her. The pair were backed up by two other members of Fuerza Nueva: Félix Pérez Ajero and José Ricardo Prieto, as well as the police officer Juan Carlos Rodas, all of whom were waiting in a car. After forcing their way in and beating her, the two men searched her apartment, and then forced her outside and into the car. They then set off toward the small town of San Martín de Valdeiglesias, to the west of Madrid.

During the journey they beat her, demanding to know about her links to ETA. After a few kilometers, they pulled the car over to some waste ground, took González out of the car, and Hellín Moro shot her twice in the head at close range. Abad, on Hellín's order, then shot her again, hitting her in the arm. "When I saw Yolanda fall, I froze; I still hadn't realized that they had shot her," Abad told prosecutors during the trial.

A few days after the killing, the police officer who had been in the car told his superiors about his involvement, also naming Abad and Hellín Moro. Hellín was staying with a friend, another police officer, in the Basque capital of Vitoria. He later boasted of his contacts in the police and the Civil Guard, his brother being a member of the latter. In the early years of Spain's Transition, links between the security forces and the far-right were widespread.

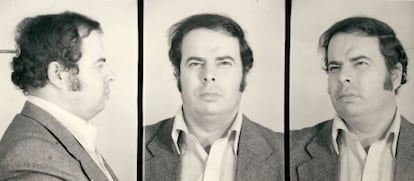

On February 7, Hellín and Abad were arrested, and confessed to the killing of González. They told investigators that they had murdered her in revenge for the killing by ETA of six civil guards in the Basque Country, suspecting that the young woman had links to the armed group. Police found a large cache of explosives and weapons at the premises where Hellín Moro ran classes in electronics. He had sophisticated radio communications equipment that had allowed him to intercept Civil Guard and police communications. Police investigators established that Hellín led an armed cell that operated within Fuerza Nueva, and that he was planning other attacks.

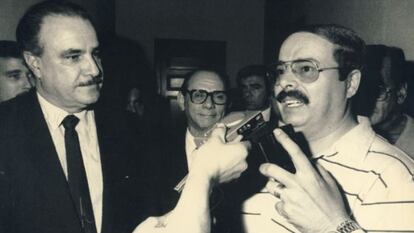

Paraguayan protection

In 1987, Hellín Moro took advantage of a furlough granted to him by prison authorities to flee to Paraguay, where he would receive protection from the dictator General Stroessner. In the photograph, Hellín Moro (right) appears with the Paraguayan justice minister of the time, Hugo Estigarribia. Hellín Moro was extradited in 1990.

Hellín was sentenced to 43 years in prison for the murder of Yolanda González. But even before being sentenced he had made the first of his prison escapes, although he was captured within hours. When he was sentenced, he was classified as extremely dangerous, and sent to the country's maximum security jail, Herrera de la Mancha. He then tried to escape while being transferred to another jail, finally managing to get away after he was granted a six-day furlough in 1987.

Taking his wife and three children with him, Hellín fled to Paraguay, settling in the capital, Asunción, where he set up a company providing IT expertise to the country's military government, led by the notorious General Alfredo Stroessner, who had links to the leadership of Fuerza Nueva. Despite operating under his second surname, Moro, he was tracked down by an investigative journalist from Spanish magazine Interviú. In July 1989, he was arrested and handed over to the Spanish authorities, and was sent back to prison, to be released in 1996.

Yolanda González's family say that they had no idea that Hellín Moro had returned to his old profession and was working for the Spanish security forces. Her parents, now 79 and 72, still live in Deusto, and say that they have never gotten over the murder of their daughter. Her brother, Asier, who was aged six at the time of the murder, says he cannot understand how Hellín Moro has been allowed to establish such links to the forces of law and order. "I cannot fathom it. It is outrageous that this man is working like this. I don't know if he has asked forgiveness for what he has done; everybody has a right to a new start in life, but if he has done so with a new identity, that just confirms the sort of person he is. It is clear that in this country, people with links to the far right enjoy privileges the rest of us do not."

Alejandro Arizcun, Yolanda González's boyfriend at the time of her death, says that Hellín's story proves that he has friends in high places: "This shows the links that Hellín had in those days with the security services, and which he retains. There was never any investigation into the involvement of certain police officers in the killing."

In recent weeks, the man calling himself Luis Enrique Hellín has made some changes to his LinkedIn account, but one chilling reference remains: "Advisor in telecommunications and IT (1988-89) to the commander in chief of the Army Chief of Staff and director general of the National Police of Paraguay."

Following the publication of this article in EL PAÍS on Sunday, the Interior Ministry and the Civil Guard have told the newspaper that they will investigate the connection between Luis Enrique Hellín and the murderer of Yolanda González.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.