What lies inside Bárcenas' boxes?

The judicial net is closing around the former PP treasurer The question worrying many is exactly what will he reveal about his party's finances

On January 16 Swiss officials reported they had found accounts containing 22 million euros registered to Luis Bárcenas, the former treasurer of the ruling Popular Party (PP). Appointed by PP leader Mariano Rajoy in 2008, Bárcenas was forced to resign a year later for his possible role in another major corruption scandal, known as the Gürtel case. Bárcenas has denied any wrongdoing, saying he was holding the money for investors.

Then, on January 21, Jorge Trías, a former PP member of parliament, published an article in EL PAÍS accusing Bárcenas of regularly handing out envelopes containing as much as 10,000 euros in cash to other high-ranking PP officials. "Outside of whatever the prosecutors and judges do," wrote Trías, "the Popular Party must explain in complete detail what means it has used to finance itself."

Last week, Spanish daily El Mundo published an article suggesting that many of the officials who received kickbacks signed receipts for the payments. And Bárcenas has also claimed that, after years of holding the Swiss accounts without declaring their contents to Spanish tax authorities, he registered and paid reduced taxes on half the amount in 2012 thanks to a fiscal amnesty passed by the PP - which by then had been elected to run the government.

So how exactly did Bárcenas come by 22 million euros? "Luis is clever and has made money," says Ángel Sanchís, also a former PP treasurer, who made his fortune in banking before entering politics in 1978. When Bárcenas opened the account in Switzerland he claimed to be involved in Sanchís's fruit empire in Argentina, La Moraleja. "It is completely false," says Sanchís. "He has admitted he did it to make a big noise. All he gave me was authorization to access his account information to assess his investments. He always thought of himself as a good stock market player. And he made money."

The nine boxes contained many secrets about the party's finances

However, a transaction for three million euros to Bárcenas' account from Brixco, a client of Sanchís, raised questions about possible bribes by Gürtel corruption network ringleader Francisco Correa. Sanchís denies this: "I put him in touch with Brixco and it seems it extended a credit line, a commercial credit between two companies. It is a clear and transparent operation."

The judge investigating Gürtel has asked police analysts to listen to a wire tap in which a man admits to bribing Bárcenas with around six million euros, to determine if the voice belongs to Correa. The recording device was hidden for two years in the pocket of former PP councilor José Luis Peñas, who uncovered the largest corruption network in Spain since the return to democracy. Dozens of high-ranking PP officials feature on the recordings, with the name of Bárcenas cropping up abundantly.

Bárcenas is taking no chances. On Saturday July 4, 2009, he took away nine boxes filled with documents from his office in party headquarters in central Madrid and drove them by car to his nearby apartment.

Bárcenas, who was the PP senator for the northern region of Cantabria, had occupied senior posts in the party for much of the previous two decades, and had been appointed treasurer the year before. But five months earlier, Supreme Court judge Baltasar Garzón had launched Operation Gürtel, an investigation into a kickbacks-for-contracts scam that implicated many senior Popular Party figures, including Bárcenas, who was about to be called to face charges of money laundering and fraud. Those boxes contained many secrets about the party's finances.

Police say he was the man referred to as LB or LBG, as well as "Luis the Bastard"

Heads had already rolled by then: mayors and councilors had been forced to stand down while awaiting trial. In two weeks, the head of the regional government of Valencia, Francisco Camps, would resign ahead of his trial.

But Bárcenas had stood his ground, despite police and tax office accusations that he was the kingpin in the Gürtel network, the man referred to in documents as LB or LBG, as well as "Luis the Bastard." The treasurer stands accused of receiving hundreds of thousands of euros in illegal commissions in return for favors.

For the moment, party leader Mariano Rajoy has stood by Bárcenas, publicly defending him and refuting the accusations. But time is running out.

Bárcenas is angry with the party to which he has dedicated the past 20 years of his life and feels the leadership has let him down, telling one colleague at the time: "I am being treated worse than Camps, and it should be the other way round, because I know things that Camps could never know about, and I have protected a lot of people over the years."

For the moment, Rajoy has stood by Bárcenas. But time is running out

Behind the complaints of ingratitude lies the implicit threat that Bárcenas will reveal the contents of the nine boxes he took from PP headquarters.

Three weeks later, on July 23, Bárcenas appeared before a Supreme Court judge. When Francisco Camps had been called to testify he had been accompanied by several senior PP figures in a show of solidarity; but nobody showed up at Bárcenas' hearing.

A few days afterwards, Bárcenas stepped down as party treasurer and went on vacation. The break with the party had begun.

Eight months later, in April 2010, Bárcenas resigned his seat as senator, and left the party, saying he wanted to focus on his defense. Until then, the party had paid for his legal costs, but now he had to pay for them himself. He also lost his 200,000-euro-a-year salary from the party.

Spotlight on PP finances

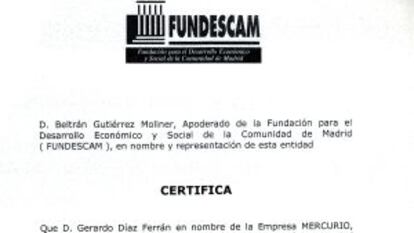

The judge's summary of the Gürtel case includes documents in the possession of the Popular Party (PP) about donations to Fundescam, a Madrid party foundation that allegedly financed election campaign events, which is forbidden by law. These include documents detailing money handed over by the disgraced former president of the CEOE employers' organization Gerardo Díaz Ferrán (above). As the alleged offenses took place nine years ago, they are now subject to the statute of limitations. The PP also stands accused of receiving donations from well-known business leaders who wrote dozens of checks, each for amounts below 3,000 euros, thus avoiding the need to declare them to the Audit Office. Luis Bárcenas would have known about these practices, and will likely have evidence of them. There are also documents showing that during the October 2004 election campaign the Madrid regional government used money from the PP-run FAES think-tank to pay for campaign meetings. Using foundation funds to pay for party rallies is considered illegal financing.

As the Supreme Court investigation rolled on, new evidence emerged against the former treasurer: money borrowed to buy works of art that he explained was a loan to his friend Rosendo Naseiro; references in documents seized by police that point to his involvement in money laundering; and the half-a-million euros his wife, who has no job or income, deposited in an account in 2006.

But the party hadn't abandoned him completely: even as the evidence against him continued to mount, the PP allowed him to use his official car, and secretary, as well as providing him with an office and allowing him to access documents stored at party headquarters.

By now Bárcenas had taken to showing colleagues documents that revealed how senior party figures used their position to enrich themselves; there are others that implicate organizations linked to the party of misappropriating donations from leading business figures.

The Popular Party receives around 10 times the amount of donations the Socialist Party does, and for the last two decades Bárcenas has counted every penny it has been given. And as the judicial net closes around him, he has begun to remind colleagues that he might find it difficult to explain the party's accounting procedures to the authorities.

Bárcenas is angry and feels the PP leadership has let him down

The Madrid High Court was also on the PP's money trail. The party's FAES think-tank received anonymous donations from well-known business leaders, among them the disgraced former head of the CEOE employers' confederation, Gerardo Díaz Ferrán. The court suspected these donations were used to pay for election campaign meetings in 2003 for Esperanza Aguirre, the then head of the Madrid regional government, organized by bogus companies within the so-called Gürtel network, and shown in their accounts, but which cannot be investigated under the statute of limitations.

At the same time, the defendants on trial in Valencia for their alleged involvement in the Gürtel network pointed the finger at Bárcenas, who rejected the accusations, again blaming party leaders for failing to back him up.

Bárcenas circulated photocopies of the dozens of checks made out to the bearer signed by leading business figures. As they are all for amounts below 3,000 euros, regional party leaders were not legally required to declare them to the Audit Office.

Bárcenas has since told colleagues at PP central office that he has evidence that the anonymous donations were used to bolster the salaries of senior party figures, who were given brown envelopes filled with cash each month - money that they did not declare to the tax office.

Behind the complaints lies the threat he will reveal the boxes' contents

Over the course of 2011, the judicial investigation would grind on, ever more slowly, and Gürtel would gradually slip from the headlines. The corruption allegations did not damage the PP's vote, and the party's showing in the opinion polls continued to improve in the run-up to the November 2011 general elections, which it won by a landslide.

In the second half of 2011, Bárcenas' fortunes improved. The Madrid High Court judge overseeing the investigation ruled there was not enough evidence against Bárcenas to bring charges and closed the case, despite not having received the results of an investigation into overseas accounts, among them several in Switzerland, to determine whether the PP's former treasurer had stashed money in secret, offshore, accounts.

By September, for the first time in two-and-a-half years, Bárcenas had grounds for optimism: the case against him had been closed, and the PP was set to win the upcoming elections. But within three months, Bárcenas was back in trouble with the courts.

In December, anti-corruption investigators and the public prosecutor successfully appealed against the Madrid High Court's decision to close the case against Bárcenas.

PP leaders say Bárcenas didn't want to break the story about the payments

Investigating magistrate Pablo Ruz questioned Bárcenas about the purchase of art works, and requested the results of investigations into overseas accounts. Bárcenas told the judge that he was the victim of a witch hunt, and that the police, the public prosecutor and the courts were all out to get him. At the end of December, Bárcenas learned that the authorities had discovered an account in Switzerland in the name of a Panamanian-registered company with 22 million euros in it.

The news wasn't made public until the new year, when Judge Ruz asked for further documentation about Bárcenas' Swiss bank accounts. At this point, part of the contents of the boxes that Bárcenas took from PP headquarters was leaked to the press. El Mundo published a story about the undeclared payments to senior PP figures, but said Rajoy and party secretary general María Dolores de Cospedal were not involved.

Senior PP leaders say Bárcenas did not want to break the story about the payments, knowing that this would hurt the few senior figures left in the PP who still supported him. Bárcenas has stated that he remains loyal to Rajoy. He believes that Cospedal is behind his downfall.

Bárcenas and his supporters accuse Cospedal of leaking information about the secret payments, inadvertently relieving him of the burden of having to do so. Cospedal and her supporters deny the accusation and say Rajoy knows who is behind the leaks.

Bárcenas' enemies know that as the former treasurer of the party currently in government, he has enough information about its finances to damage everybody, from the prime minister down.

For two decades Bárcenas has played a direct role in the financing of the PP. The party's accounts may have been approved by the Audit Office, which is five years behind in its inspection of the country's political parties, but Bárcenas knows the ins and outs of donations that sources close to him say were never officially recorded.

Bárcenas could recover his memory and reveal who financed election campaigns, or identify donations to the party that were never accounted for, say those close to him.

The former treasurer has kept quiet so far, seeking to avoid a permanent break with the party. He would prefer not to destroy the PP by revealing his vast inside knowledge of its financing, say those who know him.

They also point out that contrary to the widely held belief that he was involved in the Gürtel network, he stood up to Francisco Correa, the man behind the kickbacks-for-contracts scandal, back in 2004, when Mariano Rajoy took over the PP leadership. Along with his predecessor as treasurer, Álvaro Lapuerta, he warned Rajoy about Correa's involvement in a multi-million-euro rezoning deal in the Madrid district of Arganda involving senior figures in the regional government, led at the time by Esperanza Aguirre.

Aguirre chose to ignore the warning, rejecting Bárcenas' suspicions. The High Court is still investigating possible irregularities, and whether illegal commissions were paid by property developers Martinsa, a group that subsequently went spectacularly bankrupt.

At the same time, the party distanced itself from the Gürtel network thanks to Lapuerta and Bárcenas, who refused to allow Correa and his associates to sully the PP's name for their own short-term financial gain. Bárcenas might have hoped the case would go away when last February, Spain's Supreme Court found Judge Baltasar Garzón guilty of illegally ordering wiretaps to monitor conversations between several defendants in the Gürtel case and their attorneys, and barred him from the judiciary for 11 years, but new evidence continues to emerge.

Four years after Gürtel was uncovered, questioning the honesty of Rajoy and the party's leadership, Bárcenas continues to face charges. The PP, which, like Bárcenas, believed it was out of the woods after its landslide victory in 2011, is now fearful that its former treasurer's Swiss bank accounts will taint it once again, and undermine its credibility at a time when it is imposing unprecedented, and unpopular, austerity measures while doing nothing to improve the economy or generate jobs. The question now is whether Bárcenas will tip the balance by revealing all he knows about the PP's finances.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.