Why opera houses in Spain are struggling to hit the right note

Cutbacks mean that venues such as the Liceo need a new funding model

Despite the bitter tears, the things that the crisis has swept away will not be coming back anytime soon. Just like other sectors, European opera houses -- and Spanish ones in particular -- have lost their traditional sources of income. In some cases, funding cuts have been as high as 50 percent, and the recent value-added tax (VAT) hike on opera tickets from eight to 21 percent may have dealt the final blow to an ailing industry.

That is why the managers of Spain's main opera houses (Liceo, Teatro Real, La Maestranza, Campoamor and others, grouped in the association Ópera XXI) got together this past Monday to discuss possible solutions to their problems. Their main conclusion, besides asking the government for a VAT reduction of up to 10 percent and an art patronage law that facilitates private funding, is that they urgently need a change in the way their income is shared out.

It's not just Spanish opera that's in a state of crisis. Even the German model, based on public subsidies and artistic excellence, is feeling the pinch. Everyone is now turning to the United States for inspiration, but is that really the cultural mirror that Europe wants to look into?

In 2009 there were 1,720 opera and zarzuela (Spanish operetta) performances in Spain; these were seen by 1,203,669 spectators, half of whom were in Barcelona and Madrid. But even this is not enough, because box office revenues represent around 30 percent of total income, 10 points above the European average. Opera houses are simply not profitable, and they never will be, but if they do not find other sources of funding they will no longer be viable.

The theater has to be open to young people and the unemployed

Shedding some light on the state of things is La gestión de la ópera (or, Opera management) by Philippe Agid and Jean-Claude Tarondeau, an analysis of European and American opera houses that was presented this week in Spain. The authors' conclusions suggest that profitability is simply incompatible with the type of programming that takes risks by including modern works and in-house productions. Ultimately, programming opera is not the same as selling opera. Agid notes that Germany is a paradigmatic example of financially ruinous theater management, while simultaneously serving as a beacon of operatic quality.

For instance, while the Berlin Staatsoper premiered 31 productions between 2006 and 2007, the Los Angeles Opera, which is directed by the Spaniard Plácido Domingo, only staged 10 operas, which it exploited through 75 performances. Each ticket costs the Staatsoper 275 euros, yet it gets sold for an average of 52 euros. By comparison, the LA Opera spends 202 euros on each ticket, but sells them for 114 euros. Additionally, the Berlin theater has an occupancy rate of 81 percent, compared with 94 percent for the California opera house. What this means is that the former has a financial autonomy of 14 percent and the latter of 38 percent.

Teatre Lliure staff to get summer vacation -- but not by choice

Barcelona's Teatre Lliure has come up with a temporary labor adjustment plan that will essentially leave all of its 58 employees -- including its director, Lluís Pasqual -- out of a job for three months next summer. The measure, which was approved by the board this week, is expected to save around 250,000 euros in wages and 150,000 euros in operating costs.

The decision was triggered by the government's cuts for public subsidies.

For 2013, Teatre Lliure expects a 9.5-percent drop in income -- or 563,410 euros less than in 2012 -- a "dramatic" fall after three years of back-to-back cutbacks.

Compared with 2010, when it received more than 7.1 million euros in public funding, next year the theater is expecting a total of 5,360,049 euros.

Last season, Lliure reduced its programming by eliminating some shows; it also ended the season sooner than usual. Director Pasqual ruled out imitating other cultural landmarks such as the Liceo, which started a drive to raise funds through private donations. "People will save [the charity] Cáritas before saving the Lliure, and that's the way it should be," he said. "I always said it is logical to make operating rooms and classrooms the priority; we cannot and should not compete with that."

But despite all that, does Europe really want to follow this Traviata-Don Giovanni-Tosca model, which is based on offering a handful of very famous productions over and over again?

"I don't think America is the end-all, or that we can change the entire tax philosophy toward that model," says Nicholas Payne, former director of Covent Garden and president of Opera Europa, an association that brings together Europe's great opera houses. "What we can do, however, is learn from some of the good things: the marketing, the fundraising ability, the private donations... but these need to be applied to a European mixed economy model."

According to Payne, the proportion of public-to-private funding must change. "This inevitably has an effect on the operating structure. But I don't think it's a good idea to go toward a model with just 12 famous titles - Puccini, Mozart... That's not exactly what the Met does, but lots of American opera houses do. Our obligation is to find the combination between the repertory and the contemporary."

Paradoxically, the larger theaters have better occupancy rates and obviously can better recoup the cost of productions. The same goes for venues with more expensive tickets. The book also points out that hiring famous artists raises occupancy rates and financial autonomy.

Payne also defends making the expensive tickets even more expensive and the cheap ones even cheaper. "It's important to leave a proportion of seats, maybe 20 percent, at very accessible prices. The theater has to be open to young people and the unemployed. I think if you have a theater with a limited capacity, like the Teatro Real, you can raise the price of the more expensive tickets, because wealthy people can pay for them -- even in these times."

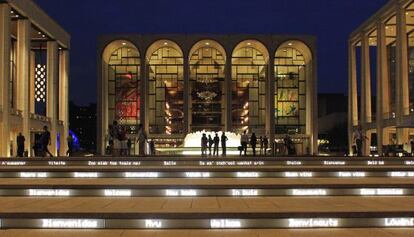

As for other sources of income, the New York Met has based part of its growth on taking its premieres to the movie theaters. Each of its productions can be seen in over 60 countries and 1,500 screening rooms, making for an additional 10 million euros in revenues - a lot more than most European opera houses would need to save themselves from ruin.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.