An avalanche of foreclosures

One Madrid courthouse alone has handled around 1,200 evictions this year Judges are not happy with this high number, but are bound by law to act

H e examines the claim with the accuracy of a forensic scientist. His hands nimbly turn the pages forwards and backwards, checking everything from the mortgage deed to the notary's certificate and the Property Register records. In just five minutes, the judge already knows the entire history of an indebted family: how much they bought the apartment for, how much it was appraised for, how long they have been in default...

In the claim that the judge is examining this Monday morning, the lender is demanding 166,000 euros from the defaulting borrowers; the mortgage, signed in 2005, was for 168,000 euros. It would seem that in all that time the family only paid 2,000 euros. But that is not the case. The judge turns a few pages again. "Look," he says. "They stopped paying in November 2010."

For five years they made their payments diligently. But it is as though all that money had vanished in thin air. That is because for the first few years of a mortgage loan, the payments mostly go toward paying off the interest, rather than the principal. And two years after this family stopped paying, the late fees have relentlessly raised the total amount owed to nearly the original sum borrowed.

The longer the legal process takes, the more money is ultimately owed. And the backlog in the Spanish court system means that eviction cases take an average of 18 months to reach a judge.

A murder crime expires after 20 years, but you can take a debt to the grave"

This family is going to be kicked out. The judge knows it, but he says there is nothing he can do: he has checked that the claim meets all the requirements to be admitted, and it is now ready for execution. The judge gets up and leaves the file on a little table in a sitting room inside his office. "I don't like to have papers on my desk," he explains.

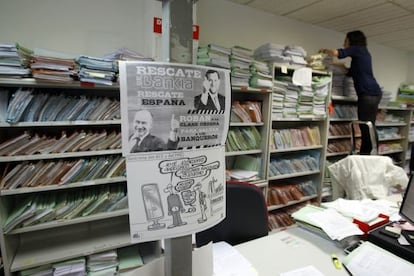

Outside his office, there is nothing but paper - reams and reams of it spilling out of shelves, piled up on the floor, cluttering up desks. They are the files of thousands of families who are going to lose their homes.

Agustín Gómez Salcedo is the presiding judge at the 32nd Madrid Court of First Instance (magistrate's court) for Mortgage Affairs. He has been here for the last 20 years. Between 9am and 2.30pm, Monday through Friday, His Honor faces an uncomfortable task - especially since 2009, when an avalanche of foreclosures began flooding his courthouse, which is located on the sixth floor of a gloomy building on Capitán Haya street.

From the window one can see the imposing headquarters of Bankia, inside one of the Kio towers that mark Madrid's skyline. Coincidentally, most of the evictions at this courthouse are being claimed by this bank, which recently had to be bailed out with public money.

In the last three years, foreclosure claims at the courts have quadrupled

On this particular morning, there are only five files on the judge's desk. But some days there are 11. So far this year, this one courthouse with 17 workers has handled around 1,200 evictions. Next to the files there is a well-worn copy of the Law of Civil Procedure - the very same law that the judge says barely gives him leeway to make decisions. But he is quite aware of the problems with the legislation that he applies on a daily basis.

Like for instance, the fact that the debt never expires (it can be claimed for the rest of the borrower's life). "I see cases where, years later, when people have rebuilt their lives, the bank reclaims the loan after repossessing the home," he explains. "It's not like that in France or Germany; after five or seven years, they wipe the slate clean."

Then he adds: "In that sense, a debtor can get worse treatment than a murderer. A murder crime expires after 20 years, but you can take your debt with you to your grave."

Gómez Salcedo has witnessed a lot of changes since he took over the courthouse in the 1990s. "There was a time when those who didn't pay actually made money on it. The home was sold for a higher price than the mortgage, and after paying the bank they still had money left over. We once had up to 100,000 euros of unclaimed money here," he recalls.

People who could have a permanent position here don't want it"

But those were different times. In the last three years, the number of foreclosure claims reaching the courts has nearly quadrupled, according to the General Council of the Judiciary legal watchdog. In the first half of 2012, evictions rose 14 percent compared with the same period in 2011. "There are lives behind this," he says, lifting up a file. "But if that's the law, you can't bypass it. I'm like the referee here."

The file that was just approved by the judge now goes to María, a 45-year-old substitute worker who is sitting in the next room, in front of a bookshelf overflowing with lots of other files. The colors indicate the year when the legal proceedings got underway: pink for 2009, blue for 2010, orange for 2011. The white ones are the worst: they are the cases in which the bank is claiming a persisting debt even after the home was repossessed. There are quite a few of them.

María says the doctor has told her that her skin is not thick enough, that she needs to make it thicker. "It pains me, I put myself in their shoes. This job really gets to you..." she says, her eyes dewy with tears. "It's very sad."

She has been doing this since January. "Most of us are substitute workers. What with the volume of work and how tough it is, people who could have a permanent position here don't want it."

What the banks are doing is unconscionable. It's so out of proportion!"

The room shows signs that the workers disagree with what they're doing. There are posters calling bankers fraudsters and others complaining about cutbacks in the justice system.

"There's just no solving this, girl," says Loli, a 54-year-old worker who has been at this courthouse almost as long as the judge.

She moves quickly, and the files appear and disappear in her hands. "What banks are doing is unconscionable. It's so out of proportion! If something bothers their lordships the bankers, believe me, that something gets changed mighty fast," she notes.

Loli deals with the debtors. "Everyone who comes in through that door has problems, although some of them don't tell you the whole truth, eh?"

There is little that can be done for them, she explains, except for postponing the eviction one month. At this point, the judge walks out of his office and both of them get incensed at the letters they keep receiving from the social services asking them to freeze evictions, even though the law does not allow it.

"The banks press for the claims to move forward. The procedure is tailor-made for them," they conclude.

However, around 100 judges across Spain have been coming up with innovative rulings that respect the law yet try to help the borrowers. Since this interview was conducted, Spain's 47 chief judges got together to produce a document criticizing what they describe as abuse by the banks and suggesting legal reforms to mortgage legislation.

"The justice system is being called upon to lead the public discourse against the crisis," the text reads.

"All we want is to be able to live with a little bit of dignity"

Time is running out for Antonio Campos, 34, and his wife Igone Aldaregia, 35, who are about to lose their state-subsidized home in a peripheral neighborhood of San Sebastián. They have four children, they are both self-employed workers with no income, and for the last two years they have survived thanks to their families' financial support and bi-weekly visits to the food bank.

Yet this couple has more to worry about than finding themselves out on their ear with four children to take care of. When they took out a loan to pay for their home, they needed two guarantors.

"My uncle backed us up with his salary and my grandmother, who is 80, with her home. If they want I'll give the bank the apartment back in payment, but I don't want them to touch my grandmother. Her home is already paid for, and she mustn't be put through the distress of being left homeless because she was our guarantor," Antonio explains.

For nearly two months they have been unable to meet their monthly payments on a 120,000-euro mortgage they took out in 2007 from Banco Santander, plus a personal loan to cover their lack of income. Four months ago they requested a state subsidy meant to guarantee people a minimum income. This would bring in 933 euros a month, but it has yet to be approved. In the meantime, they are trying to renegotiate the loan terms with the bank to pay interest only for the next three years before being considered in default and facing eviction. But it's been months since they got a reply.

"While the local office here keeps giving us the run-around, the bankers in Madrid have been sending us letters threatening us with eviction without offering any alternatives. All we're asking for is for them to readjust the debt so that we can live with a little bit of dignity," says the couple, who are desperate to find a job - Antonio is a bricklayer and Igone is a house cleaner.

To their dramatic personal situation, Antonio and Igone must add their reliance on relatives' salaries or pensions. "My mother has been paying our mortgage ever since we lost our jobs, but she lost her own job months ago and the subsidy she gets is not enough any more. Whatever money comes into this house goes toward food for my children, they are the priority," says Igone, who is angered by the fact that the public prosecutor is not represented at evictions involving minors. "Who protects them? They worry about their education and their health, but not about being left out on the street. Housing is a basic right, and it is neither fair nor ethical for 400,000 families to be out on the streets."

"The mortgage law is obsolete and needs to be adapted to times of crisis," she adds. This feeling is echoed by fully 95 percent of the population, according to the latest Metroscopia opinion survey. The poll also shows that 91 percent of Spaniards believe lenders take advantage of people's good faith and lack of legal knowledge to make them sign abusive terms.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.