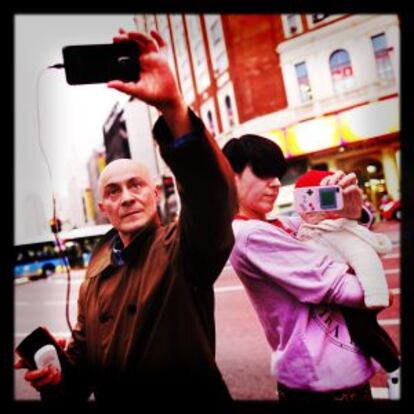

The eyes and ears of 15-S

An army of citizen journalists is ensuring demonstrations are recorded Using an array of cameras and methods, they are getting footage out to the public

It is one of the most-viewed videos of the Surround Congress demonstration of September 25, which saw thousands of people converge on the national parliament building to protest against the inability of politicians to pull Spain out of the crisis. The footage shows riot police storming the busy Atocha train station and terrorizing passengers. Although police said the officers were looking for "troublemakers," the criticism triggered by these and other images eventually forced the government to open an investigation into the events of that day.

The man behind that video is Juan Ramón Robles, a 25-year-old journalism student from Madrid who lives with his parents. At the end of his recording, which has already been viewed 1,200,000 times on his personal YouTube channel alone, you can hear him scream in outrage when a police officer yanks the microphone right off his camera. After many months using an old Panasonic LX1, he'd just paid the last installment on his 1,200-euro Canon, so the damage cut deep.

"I don't feel so much like an activist as an informer," says Robles, who is still busy phoning some of the numerous media outlets who used his video to charge them a fee (although he will not reveal how much he's earned so far). "Between having to register as a self-employed worker and the camera repairs, I'm going to lose money," he adds. The microphone is back on the camera via a do-it-yourself solution: a small screw.

"The truth is, I hate politics, but I seem destined to cover this type of information. I don't like seeing the truth being trampled on," says the photographer, who always runs in the direction of trouble at any kind of demonstration.

I don't feel so much like an activist as an informer," says Juan Ramón Robles

Like him, hundreds of people have enthusiastically embraced what's come to be known as citizen journalism. The people interviewed for this story have been to dozens of protests, home evictions and sit-ins to record or photograph developing events. Many of them are unemployed and have more free time on their hands than they would like.

A case in point is Stéphane M. Grueso, 39, who made Time magazine's special 2011 report on protestors from eight countries, including Spain. Grueso is a documentary filmmaker whose production company went bust in the crisis. "My job, co-producing documentaries for television, has disappeared, so that's why I have so much time and I help by doing what I do best," says Grueso, who is also involved in creating live streams of Madrid events.

William Criollo, a 25-year-old from Ecuador, is also out of a job and living with his parents. Sometimes he sells the odd photograph to the newspaper Diario Independiente. In the meantime, he goes out with his Nikon almost every day to cover evictions and protests. This year he'd been considering enrolling in journalism school, but the hike in tuition fees made him change his mind. Like other grassroots journalists, he's been arrested. The first time was in Paris, along with around a hundred protestors. The second time was in Madrid, where he was suspected of being part of the group that coordinated a sabotage of the subway system to protest higher ticket prices. Criollo claims he was mistaken for an activist while he was taking photographs of a group protest.

Some of the interviewees consider themselves activists, others journalists, and yet others neither one nor the other. "I am a human rights activist who uses different tools to create awareness," states Susana Sanz, 37, a business graduate and member of the People Witness collective. Sanz is yet another convert to live streaming.

Many are unemployed and have more free time than they would like

"It's a way of democratizing information, of empowering citizens. And it's a very powerful tool that magnifies information. There are times when there are more people watching a protest live than there are protestors," says this Burgos native, who feels the mainstream media "are in the hands of corporations who do not report reality truthfully."

The Popular Party government's new plan to prohibit capturing images of police officers on duty (see opposite) has particularly riled these activists. "I will go out on the street just the same. If necessary, I'll set up a camera on my helmet," says Robles.

"I find [the plan] so unbelievable that I don't think they're going to follow through on it," says Zakiah Iraultza, 24, who works for Tomalatele, an audiovisual platform for any grassroots movement with something to say, whether the cause is the environment or the fight against racism. "I think they're just trying to scare us"

"Spanish legislation says a public officer in a public space and during a public event may be recorded," argues Sanz. "It's a repression strategy; they're treating us like children, but we've already proven that we're not playing around and that we know what we're doing."

My job, producing documentaries for television, has disappeared"

The artist Nikky Schiller (of the band Dirty Princess) and her partner Vlad Teichberg experienced the 15-M sit-in that spawned Los Indignados with a communications group that formed early on, Audiovisol. When the Occupy movement began to take shape, they traveled to the United States "to teach them how to do streaming," says Teichberg, an active member of the international group Global Revolution. "It gives us a brutal financial advantage over the media, who cannot follow our pace and keep their professionals on the street for hours and hours."

On the day of the Surround Congress march - also known as 15-S, given that the first demonstration was convened on September 15 - Audiovisol offered its own coverage of the event with 20 people who were coordinated by an Italian named Paolo P. "While some people recorded with their cellphones, we gave them instructions, like 'We need a high shot! Somebody go to Atocha!'" he recalls. "We all contribute something, the key lies in working together."

Plan to ban police pictures sparks ire

The latest public order initiative by the conservative government of the Popular Party (PP) - prohibiting anyone from capturing images of the police while they are on duty - has aggravated social movements, opposition parties and even jurists, most of whom believe the measure would be unconstitutional.

Many observers feel this latest plan shares the same overarching goal as other newly announced government measures, including a tougher Penal Code; chiefly, dissuading protestors from coming out on the streets amid growing social unrest.

Although many questions about the latest government project remain unanswered, the director general of the National Police, Ignacio Cosidó, unveiled its key elements last Thursday. The goal, he said, was to prevent the circulation on the internet and social networks of police images that could put their lives at risk or violate their right to privacy. To do so, the government wants to alter the Public Security Law and ban "the capture, reproduction or treatment of images, sounds or data involving members of the armed forces in the exercise of their duties when this could endanger their lives or jeopardize the operation in which they are involved."

"It is a clearly unconstitutional measure, which collides with freedom of information," says Javier Pérez Royo, a professor of constitutional law. In his opinion, this prohibition could only be decreed in cases that evidently pose a risk to officers' lives or safety.

Police director Cosidó did not specify in which cases the recording of images might be vetoed. Sources in the Interior Ministry offered the examples of counter-terrorism operations or raids against organized crime. But nothing was said about the increasingly frequent public protests over social spending cuts, such as the recent "Surround Congress" marches.

"What they're trying to do, deep down, is to avoid having recorded testimony of potential police brutality. And the way of knowing if brutality has occurred is through visual media," adds Pérez Royo.

Jaume Asens, a Barcelona lawyer with ties to the social movements, agrees. "It's all about granting institutional impunity to police excesses. This narrow concept puts the police above the law and leaves them outside the public gaze."

So who will decide how and why images may or may not be recorded? For now, all the Interior Ministry has is a working document that does not address this issue. And this, say some lawyers, is precisely where the main problem lies.

"It could pave the way for abuse," says lawyer Javier Melero. "In a situation of social tension like a protest, can an officer make a rules-based assessment and make the right decision?"

Melero also underscores the "intimidatory effect" on the person taking the images, since he or she could be asked for ID.

Several judge and attorney associations feel the proposal oversteps the bounds of the Constitution. María Moretó, spokeswoman for Unión Progresista de Fiscales, clearly believes the measure is "a reaction" to dissuade citizen protests, "which will continue to take place against the cuts and in view of the country's impoverishment."

The spokesman for Jueces para la Democracia (JpD), Joaquim Bosch, asserts that the initiative is "out of all proportion" and violates freedom of information - especially if, as the government wishes, the ban is general and not exceptional. Citizens, says Bosch, have the right to "communicate and receive images" through any means and to report possible police abuse or excesses. "The filming of criminal action by the police will always be legal," stresses Melero.

"When you have a recorded image, the police officer could be sanctioned. Otherwise, faced with a citizen complaint but no images, the citizen's version could always be questioned, since it would be confronted with the officer's own version of events," argues the criminal expert Carles Monguilod, who also feels the government's plan is aimed more at "granting impunity to possible excesses" than protecting police officers who are already wearing a uniform and, in the case of the riot police, are already concealing their identities by covering their faces.

"The right to communicate truthful information is one of the pillars of the state," says the lawyer Jordi Bertomeu García, who considers that existing legislation already offers "sufficient protection mechanisms" for officers.

"You need to assess whether there are formulas that allow you to combine freedom of information with the smooth development of police operations and with the officers' right to privacy and physical integrity," says Marc Molins Raich, of the Roca Junyent law firm. Molins believes this is possible because "these days, computer programs allow you to disseminate images while protecting the privacy of the protagonists." In this case, he says that "perhaps" the ban is unnecessary and it would suffice to draft protocol for the media.

Armed with a cellphone and/or handheld camera, any citizen can now be a purveyor of information through the internet and the social networks; besides, the multiplicity of platforms makes online persecution complicated. The uncontrolled presence of images of police officers on the web is a matter of some concern for the Interior Ministry. It happened during the March 29 protests in Barcelona, when Catalan plainclothes officers were identified online.

The media enjoy special protection, notes the university professor Pérez Royo. But freedom of information is also the privilege of individuals. A person may upload a photograph and a video on to the internet, and add a comment for instance. In this case, he or she is exercising freedom of expression.

The president of the Federation of Journalist Associations of Spain (FAPE), Elsa González, warns that the government's announcement "sounds like censorship" and deprives citizens of the right to truthful information, using the pretext of protecting the police - whom, she notes, must carry visible ID at all times. "We do not support any restrictive rules; we do support responsible self-regulation."

One of the police unions' concerns is that images of police actions can later be ridiculed on the social networks. Or, what's worse, they can be used to initiate a harassment campaign against specific officers, if their names and identities are revealed. In any case, said Cosidó, the ministry is trying "to strike a balance" between both positions.

As for opposition parties, the Socialists have asked Interior Minister Jorge Fernández Díaz to appear in Congress to explain the measure. Meanwhile, the congressional spokesman for United Left, José Luis Centella, called the plan "an attempt at censorship."

"The PP continues along its usual lines of being the party of the baton and the party that likes to criminalize protests," he said.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.