Spanish songstress who was "up there with Piaf"

New show remembers singing legend Raquel Meller

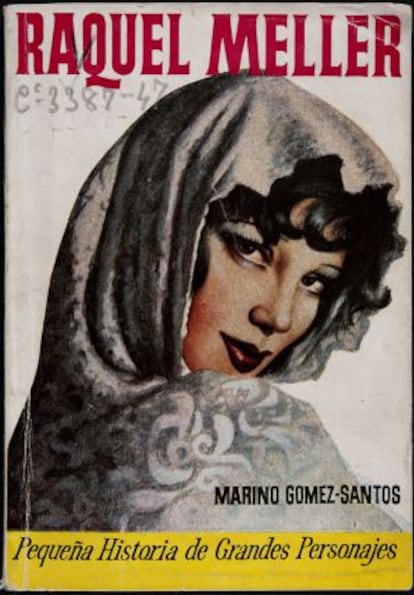

In the first third of the 20th century, the cuplé genre of variety songs became the soundtrack of a country on the brink of war. And with her high-pitched and theatrical voice, Raquel Meller was its finest exponent. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of her death, the National Library in Madrid is hosting the exhibition El mito trágico de Raquel Meller (1888-1962) (or, The tragic legend of Raquel Meller.)

"Nobody knows where the unique genius that made her a star came from. She didn't have an education, though she did have intuition and intelligence," explains exhibition curator José Luis Rubio, standing in front of one of the display cases showing the first recorded version of José Padilla's cuplé La violetera.

"It is true that the composer didn't write it for her, but Meller had the ability to make it hers," says Rubio.

With its coquettish and typically Madrileño lyrics, it is perhaps the song for which Meller is best known, but the exhibition also takes care to remind visitors that she was an internationally renowned star who also sang songs in Catalan and Basque while entrenching herself in Paris, where she spent the best part of her life before heading off for Latin America.

Prior to coming back to a Spain she no longer recognized, and that had forgotten her, Meller traveled to the United States. She landed in New York in 1926 thanks to an American impresario who paid her an advance in case she changed her mind. In front of an audience dotted with such characters as newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, Meller sang 13 songs, all in Spanish, starting with El relicario and finishing with La violetera. But before offering La mimosa as an encore, she appeared dressed as a prostitute, walked to the edge of the stage and lit a cigarette. She smoked it indifferently while she sang, finishing up against the wall, without strength, without life. The next day she was on the cover of Time magazine.

"Raquel Meller is at the level of Piaf, Sinatra, Callas and Carlos Gardel," says Rubio. "Because of the high level of her performances and her way of understanding art. She concerned herself with her work, but when she left the stage it was the problem of others to speak about what had happened." He adds that she had "a very unfriendly character. She was very individualistic and foul-mouthed." One of the few people who understood her a little was the son of painter Joaquín Sorolla.

As lonely as the beat-up prostitutes of whom she sang, a gray-haired Meller died in obscurity. She had been surpassed by a new generation of artists.

"The last report of one of her performances in Madrid talks about the astonishment of an audience who had forgotten her distinctive way of interpreting popular music," says Rubio.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.