"Franco didn't allow peace because he was bitter"

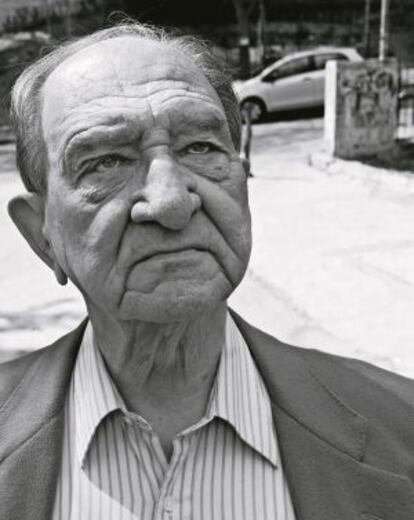

Historian Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz talks about his book, Prisons and exiles

There is a lot of anger in Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz's book about his time first as a prisoner under Franco in the dictatorship's most emblematic prison, the Valle de los Caídos, or the Valley of the Fallen (which he always refers to as "Cuelgamuros," from the Spanish Cuelga Moros, or Hang the Moors), and then as a fugitive.

From Madrid and the son of Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, an eminent historian and president of the Republic in Exile, the 84-year-old has taught at various universities throughout the world. He is Professor Emeritus at New York University, and was the first director of the Cervantes Institute. Today, he lives in a house overlooking his home city, where he wandered as a member of FUE (Federación Universitaria Española, or Spanish University Federation), which grouped together dissatisfied students in the post-war period. Until the police caught up with him and his colleagues in the anti-Franco fight, that is. Their capture ended in unreasonable sentences, doubled in length by the brutality of the time. The escape of Sánchez-Albornoz and his fellow prisoner Manuel Lamana from the slave labor practiced at Cuelgamuros in 1948 was one of the legends that most damaged Franco. The prisoners were aided in their escape to France by anthropologist Paco Benet (brother of Spanish novelist Juan Benet), American journalist Barbara Probst Solomon and Barbara Mailer (sister of Norman Mailer).

In the democratic era, the escape formed the basis of a film by director Fernando Colomo (Los años bárbaros, or The Stolen Years) and of a book by Probst Solomon, along with many other publications. As a consequence, Sánchez-Albornoz didn't want his book, (Cárceles y exilios, or Prisons and exiles, published by Anagrama) to revolve around this episode. But it is in there. Above all, the book is an expression of anger: Cuelgamuros, the Valley of the Fallen, was a major symbol of Franco's desire for vengeance - he wanted to humiliate his adversaries. It is there where our conversation begins.

Question. You write: "The Franco regime never conceived of peaceful co-existence among Spaniards without political exile."

Answer. That is clear. There was a war, and the victors had to finish it off. That may mean brutalities and persecutions but the victor is always abusive. What happened with the Franco regime, however, was that this went on systematically for 40 years after the war. In World War II, there were also victors and the vanquished, but two years later, it was all settled. Why couldn't Franco settle up in two years?

Q. Why not?

His prison escape in 1948 was one of the legends that most damaged Franco

A. Because he was a bitter man who was not interested in a peaceful existence for Spaniards, but in maintaining power.

Q. And he continued the executions until the end.

A. There were different stages: the period from 1939 to 1942, for example, in which, according to reports from the time, more than 100,000 people were executed. But my account is not from that time as I didn't experience it firsthand. My account begins in 1947, and I am sure there were still firing squads then because I lived through it. The executions lasted until Julián Grimau in 1962. Supposing that the Allies still had reasons for killing people, they did so quickly. That didn't happen here. In Spain, Franco kept killing after the war. Grimau was executed for war crimes.

Q. When you finish your book, you are left with the feeling that our history has been ill-fated. How did you feel writing it?

A. I was at peace. As far as ill-fated goes... no, it's not ill-fated. The history of Spain would have been very different if this intrusion had not taken place. In its economic history, it is clear that Spain was more or less gaining ground. And then the war came, and the Spanish economy went into rapid decline, not returning to its 1927-1928 levels until 1956. And this same deterioration took place in social relations and cultural life. Without the war, for those 40 years that the Franco regime lasted, Spain would have had a much higher level than it did in 1976.

Q. The regime ended. But when your father returned from exile in 1976, then Interior Minister Manuel Fraga Iribarne prohibited a formal dinner in his honor. So, the regime was still there.

After the Transition, the escape formed the basis of a film and a book

A. And it is still here today. There is a de facto group, which stands for everything that fuels that dark side of a segment of the Spanish population. But they are not Spain. Spain is something different. I think it's clear that if Spaniards had been left alone, Spain today might not be the most brilliant country, but it wouldn't have been that of the Franco regime.

Q. How did you and your father feel when Fraga prohibited that dinner?

A. At the time, we weren't happy about it, but neither were we surprised. Fraga was a person who was very involved with the Franco regime, a conformist. I state several times in the book that the only thing that allowed the Franco regime to exist was conformism. The regime established certain rules, which were very cruel at first, and after it had to survive in a world that had turned its back on it because Germany had lost the war; so the regime tried to conform, while remaining as true to its original line as possible. But it couldn't maintain it in all aspects.

Q. Given what you say, as well as the controversy over the sentence handed down to Judge Garzón, what do you think should be done regarding Historical Memory?

A. First, all the cards should be laid on the table. Everything must come out, and that's what we have historians for. The post-Franco state has taken great care to ensure access to government and military sources has been closed. Historians have made great strides but they haven't managed to clarify everything. First, the truth has to come out and after that it must be made public. Finally, the descendants of the victims must be given closure.

Q. The issue of Historical Memory and the Garzón case prove that Francoism is not dead. In that sense, the judge is a new victim.

The post-Franco state has ensured access to government sources is closed"

A. Of course. Although I would change your wording ever so slightly. It's true that Francoism has not died out, but you have to add that what remains just represents a segment of the population, because other groups will not have it. Unfortunately, it is quite a large segment that is still very active in the social and political apparatus of the country. But it must be acknowledged that the majority of Spaniards are disgusted by these things, and in general, Spaniards are much better than those nuns who stole the babies.

Q. Your book counters the image of Franco as an austere man.

A. The entire system was corrupt. Franco's authority rested on two elements: death and punishment, and corruption. To me, this is evident and I would like people who weren't there and didn't live through it to understand this. Everything was based on corruption.

Q. You said that Spanish society is better than the Franco regime. But are there significant residues of Francoism in our society?

A. Yes, of course, starting with the justice system. And the Church. I don't have a lot of evidence, but I have one piece that I will mention: when the head of police at Porlier prison had finished reading a list of people who were to be executed the next day, the priest there asked, "There aren't any more?" One of the prison staff told the story later; this same corrupt civil servant who dabbled in the black market was taken aback by the priest's dehumanization. There are witnesses in the Church to the hierarchy's collusion with the Franco regime. The pressure the Church exerted on social life was monstrous. It's what [Archbishop of Madrid] Rouco is missing, because though he might be saying mass, nobody is paying any attention.

Q. You have written that "Memory is not restricted to the past, but is a guarantor of the future." That is at the root of your book.

People should understand that everything was based on corruption"

A. I took that from the comments of a Polish Jew who had emigrated to Canada and was speaking about the situation in Poland today. He found that because things had not been spoken about, national integration and, in part, the integration of Jews within Polish society were weakened. Memory is not just an act of remembrance. Full memory is also necessary to reestablish peaceful relations among citizens. And it's the future that matters, not just knowing the truth, but it is something that is necessary for national co-existence. This contrasts with Franco's previously mentioned desire to prevent co-existence - because in order to live together peacefully, knowledge of the past is needed. Franco was not interested in having that past revealed, and he tried very hard to taint the image of the past. So the question that must be considered is whether we are interested in the peaceful co-existence of Spain's various groups or not.

Q. You were the son of a Republican, and consequently, a communist. After the police arrested you and you were tried, what were you thinking when the sentence that would send you to prison for eight years was read? Did you say to yourself, "No, I don't want to spend that time in prison?" What went through your mind?

A. I have managed to reconstruct events in detail. There was a first request sent to the prosecutor. Later, a second request was sent for him to reduce the sentence even though the Council of War was being held. They didn't tell us the verdict right away, maybe because the international press was there, and it was 1948. The moment of truth came at eight in the evening: the sentence was brutal, even harsher than the one the prosecutor had requested. I became enormously angry, and decided that I was not going to stand for it.

Q. And the idea of the escape was hatched...

A. A friend of mine, Luis Rubio, spoke about it to the CNT, which had begun planning escapes. The truth is that the CNT were very good to me, and they included me in a plan they had drawn up.

Q. It must take nerves of steel to escape from Cuelgamuros...

The period we are going through right now won't shine in the history books"

A. Yes, or a lot of youthfulness, or will to live. Fernando Olmeda says in his book that there were 44 escape attempts, including ours, and ours was the only successful one. The rest of them ended up going back to their home village, and they caught them there. We went abroad, that was our plan. We were very quiet about it, not many people knew. We waited at the gate; we were two young men, Lamana and myself, and two young foreign women, Barbara Probst and another Barbara, Norman Mailer's sister, in a car that was very apparently American. It wasn't a group that would raise the suspicions of the Civil Guard.

Q. There was a period in your life when you founded the publishing company Ruedo Ibérico along with José Martínez, which was historically significant in terms of reconstructing how to tell Spain's story.

A. I set it up it for two reasons. We reached the conclusion that the regime at the time had created an ideology that had successfully spread. People might not agree with the Franco regime, but it had soaked through even into their language. They spoke easily of the glorious uprising, and they were talking about the communists. They might insult Franco, but they had swallowed all of the Franco regime's propaganda. So we saw that there was territory there that could be worked by publishing stories that could open their eyes. I think that with Ruedo Ibérico, we managed to do that. It was a success because these books immediately had a large following and an impact in Spain.

Q. Exile allowed you to get to know that migrant Spain in which your father was already living. France, Argentina, America... What were your impressions of this world and how did yoou find your father?

A. In Buenos Aires, I met a lot of people that I had previously heard or read a lot about. Rafael Alberti, for example, in Cuatrecasas' house. There were thousands of Republicans in Buenos Aires. They held talks, they shared and talked about their own experiences, and that kept the Republic and the Civil War very alive there. It was useful for learning about what was not being spoken about in Spain. But the Spain of that time was not very present. They had created their own world, but they had little knowledge of what I had left behind. So I soon began to circulate with Argentinean students, whom had had experiences much more similar to ours.

Q. How did your father's relationship with his adopted country develop?

What is alarming in the current situation is the level of improvisation"

A. He never stopped longing for Spain. He even kept a watch set to Spanish time in one pocket, and one set to Argentinean time in the other. And his students and colleagues kept him up to date, not so much politically, but culturally. He also knew what was going on through his contact with other Republicans in Mexico and France, who wrote to him or sought his opinion.

Q. And your return in 1976? You came back together.

A. It was a very emotional moment because all of that longing could be finally satisfied. He jokingly said he had run a race against Franco, and Franco had won. He was quite advanced in years when we returned, and at that age, it's hard to give up the life you have built. What's more, he had his students, his magazine, and it was hard for him to give that up, which is why he returned to Argentina.

Q. And how do you feel in this country?

A. Looking back, and I think that is what the book does, I feel good. It's not the Spain that I knew; we are going through a period right now that won't shine in the history books, but even so...

Q. How do you see this current period?

A. There is a global economic crisis led by the financial system and its abuses, which in the case of Spain has been worsened by a dreadful economic policy created by the PP in its last government to give free reign to the real estate sector, which resulted in a certain level of euphoria at the time. And Zapatero didn't put a stop to it; he didn't know how to burst the bubble. What is alarming in the current situation is the level of improvisation. The government doesn't know what to do so it is improvising. Improvisations and dehumanization... There is a return to certain Francoist roots in society, and that is worrying. A very unpleasant Spain is surfacing. The big difference from the Franco regime is that an authoritarian regime designed by a party was imposed, and so far in Spain, the principle of free elections is being upheld. So at least there is some hope.

Q. Do you think the Republican spirit still lives on?

A. There are two Republican spirits: one is evocative of the Republic, and the other is a new kind of Republican spirit, found in people who were not Republicans in 1931 and may ignore the period from 1931 to 1936, but most certainly question why that man should be king. It's a rediscovered republicanism.

Q. You have had a very long life. Notable moments?

A. There have been a lot. My return to Spain was very moving, of course.

The longest journey

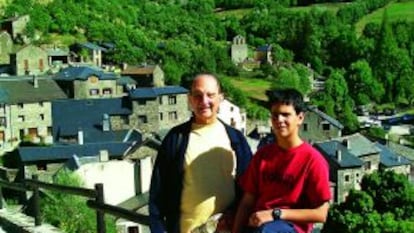

- Journalist Barbara Probst Solomon and Barbara Mailer, sister of Norman Mailer, dropped Sánchez-Albornoz and his companion Manuel Lamana off at the foot of the Pyrenees after taking them from the Valley of the Fallen - the prison that symbolized Franco's cruelty towards his enemies - outside Madrid to the French border.

- The two fugitives were lost for hours, an experience that Sánchez-Albornoz recounts in detail in his book. "It wasn't so much symbolic as necessary. We couldn't got to Gibraltar, nor to Portugal. It had to be France," he says today.

- The above photo shows him with his grandson Ayman el Dahrawy

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.