Brazilian leader stuck between a forest and a hard place

Rousseff threatens to veto law that will change the Amazon protection code

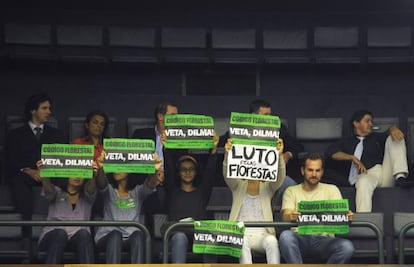

Just weeks ahead of the World Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil's Congress has put President Dilma Rousseff in a tough spot by passing a bill that places the interests of farmers over the preservation of the Amazon rainforest.

On April 25, deputies in the lower house backed changes to the so-called Forest Code, easing rules regulating the amount of forest that farmers must protect, backing the country's powerful agriculture lobby and inflicting political defeat on Rousseff, whose only option to try and stop the bill is by using her presidential veto.

Should she choose to knock the bill down now, the farm lobby in Congress could overrule that veto in turn with a simple majority vote of 50 percent plus one vote. The latest law was passed with 60 percent of lawmakers' votes in favor.

In June, Brazil will host the Rio summit, a meeting at which government leaders and policymakers from around the world will discuss global environmental policy.

The long-running arguments surrounding the bill have been watched closely inside and outside Brazil, home to the world's biggest rainforest and a country considered a point of reference for how other developing nations manage their woodlands.

Though the bill will require millions of hectares of already cleared land to be replanted, environmentalists expect it will make it too easy for farmers - responsible for much of the deforestation of the Amazon and other swaths of environmentally sensitive land in recent decades - to comply with regulations that stipulate how much forest they must preserve or put back.

The law will leave it up to individual states to decide how much forest needs to be replaced along riversides, meaning that big farming states may only make minimal demands of growers to favor agribusiness, a clause that has infuriated environmentalists.

Rousseff had made it clear during months of debate over the new law that she would veto any bill that could be perceived as an amnesty for farmers who flouted minimum forest coverage requirements in the past.

The bill made it through the lower chamber of Congress despite Rousseff's overwhelming majority because the powerful farming lobby within decided to side with agribusiness interests instead of backing the government.

Around 61 percent of Brazil's territory is protected by law, while 27 percent is dedicated to agriculture. The agro-industrial sector contributes 37 percent of jobs, 27 percent of the nation's GDP, and provides 37 percent of all exports.

For environmentalists, including Greenpeace and the World Wide Fund for Nature, the law is a clear step backward, no matter how it ends up being regulated, given that it will free farmers from replanting forest they were obliged to maintain under the old law but often did not.

"The approved bill gives a total and unrestricted amnesty to those who deforested [...] and goes against what the government itself had wanted," Greenpeace said in a statement. "If [Rousseff] doesn't react and veto this text, this will be her legacy."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.