Luis Buñuel: intimate and unedited

The Filmoteca Española has stumbled upon unseen home movies shot by the Spanish director during his time in exile in the United States

There was a time when Luis Buñuel was convinced that he would never shoot another movie. Those were the tough early years of exile in the United States, immediately after the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), when the country's most brilliant artists, scientists, politicians and intellectuals were scattered across the globe.

He lacked technical teams, top-billed actors, money and surprising stories to tell, yet the director of Un chien andalou, Belle de jour and The discreet charm of the bourgeoisie made do with a home movie camera, which he used to record personal moments with his family and friends. Those rudimentary, improvised shots of his two children, his wife Jeanne and friends such as Juan Negrín and Rosita Díaz Gimeno are seeing the light now thanks to the work of Javier Herrera, a librarian and Buñuel scholar at the Filmoteca Española in Madrid.

These candid images show the most intimate side of the master of surrealist film; a man who sometimes had trouble producing a smile, and who spent hours playing board games and whiling away the time at borrowed country homes. For years the films were known to exist but had been lost. It was only years later, when Filmoteca researchers rummaged through the boxes filled with documents, books, letters, notebooks, Civil Guard hats and wigs that made up the artist's legacy, that these home movies emerged to shed some light on an artist who was as fascinating as he was mysterious.

There are eight minutes of footage shot in his New York apartment on 83rd Street, in Central Park and in a country house in Maine: "Very likely the house of his friend Alexander Calder," says Herrera. The footage is divided into two distinct parts: one devoted to his newborn, Rafael, and another one focusing on his eldest son, Juan Luis. Seventy years later, sitting in his Paris home, Juan Luis still clearly remembers those moments spent in exile.

The first image shows a toy train. "That train! I remember it perfectly," says Juan Luis Buñuel. "One day, I was calmly playing with it when my father, Joan Miró and Calder showed up drunk. They kicked me out of the room and started playing with it themselves."

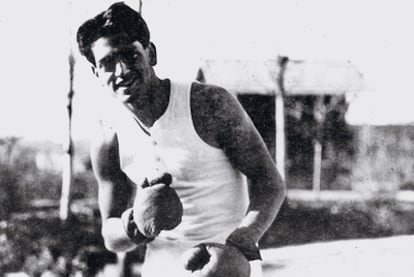

At once a father figure and an eternal child, Luis Buñuel spent his life torn between absolutely contradictory behavior, impulses and reactions. He was a fan of boxing and insects, a lover of cocktails, a voracious reader, a male chauvinist and a delirious Surrealist, yet a devoted father. Everything is exposed in his films without any kind of explanation or hint - he just lets himself get carried away by the motto that ruled his life and art: "Horror of understanding."

In My Last Sigh, his brilliant memoirs, Buñuel formulates another phrase that functions as an engine for his creative mind: "The joy of receiving the unexpected." The surprise, the dream, the sudden outburst, the ineffable and incorruptible guide of imagination as a vehicle for unshackled creation. That was his only law.

That is why Buñuel was many things in life and in art history. He was a guiding light for the turn-of-the-century avant-garde movements in Paris, which he and Salvador Dalí awed with Un chien andalou and L'âge d'or. But he was also an inspirational figure for the members of the Latin American boom, whose Mexican members adored him. He also left a mark among the great Hollywood directors, from Alfred Hitchcock to John Ford, George Cukor and Billy Wilder, who toasted him during his brief return to Los Angeles.

The film critic Carlos Boyero, a longtime fan of Buñuel, says of the footage that "to see someone who knows himself to be iconoclastic and wild absorbed in a game of checkers, enjoying his prime and his maturity, make it a unique document."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.