Rajoy's long and winding road

The opposition leader is staging his third successive bid to head a national government, and this time, if the opinion polls are to be believed, he will put the Popular Party back in power after seven years of Socialist rule

Short of a disaster, on Sunday November 20, Mariano Rajoy will be elected prime minister of Spain. Such is the mood of confidence within the Popular Party that Rajoy's colleagues say he has already mentally put together his Cabinet. Nobody has ever accused him of being charismatic, but he has surprised many in his own party for his survival skills, playing a waiting game since the crisis hit in 2008, biding his time and sniping from the sidelines as Prime Minister José Luis Zapatero's popularity hit new low after new low. He has criticized the Socialists, while artfully avoiding committing himself to any alternative strategies to tackle the crisis. Instead, as the title of his newly published memoirs suggests, Spain is going through a crisis of confidence, and what the country needs is a man it can trust. "At times of difficulty, people want sensible, realistic and prudent leaders," say his party colleagues, explaining his appeal to voters this time round.

"Hey, listen, Rubalcaba is clearly a much older man than me; he is 60 and I'm only 56"

"He is not a manipulator or a plotter, which is why the grassroots support him"

"He is where he is because of his own merits, his clarity, and his analysis of Spain's problems"

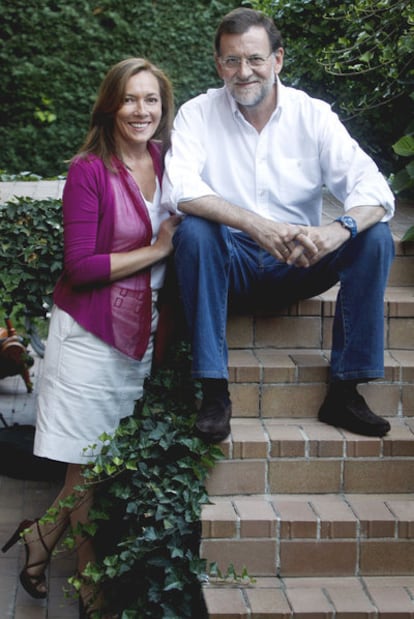

Sitting at his desk in the Popular Party's central Madrid headquarters, Rajoy looks relaxed and healthy after his summer break, and says he is ready for the two-month fight against the Socialists' Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba. The two men have much in common, with many years service to their respective parties that have taken them to the deputy leadership, and now, one last chance at the top job. On a more personal level, they are both supporters of Real Madrid, and neither has much time for current coach José Mourinho.

But Rajoy insists, with good humor, on dismissing any similarities with his rival: "Hey, listen, Rubalcaba is clearly a much older man than me; he is 60 and I'm 56."

- Victory seems assured.

- Nothing is assured. For the moment, Rubalcaba and I are tied at 0-0.

- Apparently you have been in close contact with the prime minister recently. Now that he is standing down, what is your assessment of his legacy?

- The point is that he has got things completely wrong about very important issues, and has not been prepared to listen to anyone. As we approach the end of his term, he is showing signs of trying to get things right; perhaps he is finally coming to terms with reality.

- But on a personal level your relationship is good.

- Right.

- What do you think about the fact that a politician like Zapatero, who has accumulated huge experience, is now to disappear from the scene?

- He has some political value, sure, he has learnt a lot, and we have to respect the decisions he took. I don't agree with the idea of pushing young people into the job at any cost. If I have to appoint a minister who is 30, I will, and if I have to appoint a 75-year-old, I will. Age isn't important.

Rajoy has come a long way since the Socialists' surprise win in the 2004 elections. Defeat four years later unleashed a war of succession in the Popular Party that he has finally managed to contain, although the party leadership remains ideologically divided. Even before the final count was in on March 11, 2008, his enemies in the party were sharpening the knives, and there was open hostility toward him as he made his way through the PP's headquarters to speak to supporters from a balcony. Telemadrid, the capital's television station and longtime propaganda vehicle for Esperanza Aguirre, the head of the regional government, was especially critical of Rajoy's leadership.

Rajoy prefers not to dwell on the internecine conflicts that ravaged the party until the crisis bit. "I don't remember much about that night, except that we were all very emotional; it was one of those unhappy occasions that you learn from and that make you stronger. Some commentators interpreted my goodbye as I left the balcony as my resignation, but it wasn't like that. You don't take important decisions like that in the heat of the moment. Over the next days, there were some in the media, who, not to put too fine a point on it, questioned my leadership."

Some sectors within the country's rightwing media turned on Rajoy, particularly the Cope radio network, controlled by the Roman Catholic Church. Rajoy even met with the head of the Spanish synod, unsuccessfully asking the bishops to tone down the outlet's criticism. His recently published autobiography-cum-vision for Spain, En confianza (In confidence) skips over this period of internal division within the party, referring sensitively to "breaks with party colleagues" and summarizing the whole episode as "painful."

One senior colleague of the PP leader admits that there was a plot to get rid of Rajoy involving former Prime Minister José María Aznar, Esperanza Aguirre, Pedro J. Ramírez, editor of the rightwing daily El Mundo, and the Catholic Church's media attack dog, commentator Federico Jiménez Losantos.

But Rajoy knew where his support lay: in the party's grassroots. He set about garnering that support through a party organization that he had largely set up, and which he still controlled. Regardless of the campaign within the party to sideline him, Rajoy won 84 percent of the vote at the 2008 party convention, and although his adversaries did not back down, the subsequent victories in the regional elections in his home region of Galicia, followed by success in the European elections of the following year, bolstered his position.

So what is the secret of his success; how did he fend off the baying pack of critics? "I am leader because my colleagues in the party have decided so," he explains with a candor that might be interpreted as irony.

His supporters vehemently deny that Rajoy has side-stepped his enemies through subterfuge, or that he has used others to get them out of the way. "He is not a manipulator; he's not a plotter, which is why the grassroots support him. He is intelligent and intuitive. Basically he is a good person, and a very human one," says Rajoy's protégé Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría, the PP's spokeswoman in Congress. "He has avoided having to elbow people out of the way, or to have to fight. He is where he is because of his own merits, his clarity, and his analysis of the problems facing Spain," says José Manuel Romay Beccaría, a veteran of Spain's democratic right wing, and to a large degree, Rajoy's political mentor.

"Holding on to the leadership of the PP isn't something that can be done through laissez faire, laissez passer. The key to Rajoy's survival is his ability to get the timing right. He is a master at this, because he seems to achieve his goals without seeming to do anything. He is sensible, frank, although some see him as hesitant and slow to react; but the truth is that he thinks things through," says Xavier Pomés, a member of the rightwing CiU Catalan nationalist bloc, and an old friend of the PP leader. Others who have worked with Rajoy from other parties agree that he is a man of his word, and that he would always meet his obligations. The charges of hesitancy come from within his own party, with some saying that his refusal to be drawn on issues of the moment give the impression that he is out of touch or ill-informed. He has also been criticized for his perceived failure to deal with corruption in the Popular Party, notably the Gürtel kickbacks-for-contracts scandal that led to the resignation of the head of the regional government of Valencia, Francisco Camps. It is still an issue he refuses to discuss.

- Do you think that you have handled the Gürtel case properly?

- At the end of the day, it is the courts that decide if somebody is guilty, something that many people tend to forget. But a sentence issued by the media has no appeal, and there are many cases of people being accused of things that the courts then dismiss.

- Are you referring to a particular case?

- No, I am simply saying that I have to be fair when I make a decision.

- So if would take a judicial decision for you to act?

- Not necessarily. We have responded in political terms to each of these cases. All those involved in corruption have been removed from office.

- So Gürtel has been completely cauterized?

- There are still cases being investigated, such as the three deputies in Madrid, who, by the way, have resigned.

- What do you have to say about Francisco Camps?

- He has resigned as head of the regional government of Valencia despite our conviction that he is absolutely honest.

- Are you aware of the existence of a corruption network that involved senior members of the Popular Party?

- There are clearly things that have happened, which don't look good, and that we will try to prevent from happening again.

Following his victory at the 2008 party convention, Rajoy seems to have grasped the reality that he was not going to be able to make everybody in the PP happy. "Some told him to get Aznar out of the picture, but as Mariano cannot be something he is not, he decided to put his personal stamp on the party; that's why there are now people who back him," say his supporters. At the 2008 convention, the PP was able to calm the waters, and thanks to Rajoy, able to project itself as a moderate center-right party. "It isn't enough to be right, you have to get others to accept that you are. It is fine to have strong convictions, but you have to accept that others also have different ones. A politician who really wants to govern can't live in isolation; you have to talk to everybody." These are just a few of the principles that Rajoy has tried to get the party to accept. His project has been to try to shift public opinion away from seeing the PP as backward-looking, confrontational, intolerant, and divisive; we should not forget that several senior party members seriously proposed a boycott on Catalan cava over the issue of the regional government's demands for greater autonomy. Similarly, the PP is identified with that sector of Spanish society unprepared to make the kind of sacrifices required for political settlement in the Basque Country.

So is the PP really a part of the moderate center right, as Rajoy would have us believe? What about the party's more rightwing, reactionary elements? According to Rajoy's supporters, the PP's more moderate image began to take shape following the 2008 convention, distancing itself from the hard right that still runs the Madrid regional government, and which uses its position to stir up confrontation over issues such as abortion, same-sex marriages, or religious education.

"I think that the confrontation in this country is a media issue, not a political one. If during a speech I spend 15 seconds criticizing the government, that will be the headline in tomorrow's paper. At the same time, one of the most important political steps in modern history has been taken in the Basque Country. Thanks to the support we have given to the Socialists there, we have put an end to the idea that only the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) can run the Basque Country," says the head of the PP in the Basque Country, Antonio Basagoiti. He adds that Rajoy has respected the pact with the Socialists to run the region, regardless of the tension between the two parties at the national level. "He is a sensible man. I have heard him tell me at conferences that the inquisitorial approach of this or that speaker wasn't helping their argument. He is somebody who also likes to talk about other things than politics. At Christmas, he likes to spend a little time with us just having a drink and chatting things over."

José María Lassalle, a PP deputy who is part of Rajoy's inner circle, describes him as one of the true representatives of Spain's moderate, federalist, regional bourgeoisie. "He is a moderate conservative, with a vision of the world influenced by his origins in Galicia, a vision that looks out to the Atlantic as well as being provincial. He has been able to run the party because he has been able to hold on to his centralist vision," he says.

"Your party has shown little support for the government over a number of questions of state. Your refusal to accept the measures demanded by the EU almost brought about an IMF/EU intervention. Many people asked themselves whether the PP was really qualified to govern," I say to Rajoy. "On May 5 I met with the Prime Minister, and after offering him my support for some aspects of the restructuring of the financial system, I made clear the need to reduce the public deficit. He told me he did not think that was necessary, but one week later, without having spoken to us about it, he outlined a plan to Congress of cuts along the lines of 'take it or leave it.' That's no way to run a country."

But what of Rajoy's proposals to get Spain working again? The opposition leader does not pretend to have any magic solutions to the unavoidable economic, political and administrative changes he will have to implement. Instead, he gives the general impression that a change of government in itself is part of the answer. Does he intend to oblige the regions to respect European legislation on transport, the environment, and other issues?

"We have handed over monetary and exchange policy to the EU, and we are working to harmonize areas such as corporate tax. At a time when we are working toward greater European integration, we cannot allow our regions to apply different rules."

- Can we talk in terms of a collective failure for not having been able to spot and correct the inefficiencies of the system and for not having created a more competitive economy?

- It's not the system that has failed, but our leaders for not having controlled spending or implemented the changes that the euro required. The private sector has been allowed to slide into debt and now that money has to be repaid. We have lived beyond our means thanks to easy money. Then there are more intangible issues like recovering values such as effort, the value of work, justice, respect, and although it sounds old fashioned, good manners. We have fallen into the trap of thinking that one can get to the top without effort or merit. We live in a world in which thought has been replaced by spectacle.

- Are you talking about the television?

- The only limit on freedom of expression should be the Penal Code, but those who run the media must also think about their role in society: they have a social function as well as a money-making one.

- In your book you talk about the need for structural reforms in the labor market, about education, about R+D... how do you intend to go about implementing these changes?

- We have to respect the conditions that the EU has imposed on us, and the regions have to accept spending limits. But it isn't about decrees; it's about trust, which is the basis of the economy. Trust requires the government to carry out its plans, and not to change its mind every five minutes. This is about being decisive, about people knowing that they can trust us - this isn't going to be easy. We have a youth unemployment rate of more than 45 percent - young people with a good education looking for work abroad. There is a feeling that this generation will be worse off than their parents. There is nothing worse than uncertainty and insecurity, but we can't be apocalyptic. We have to move forward. In the past Spain has shown that it can generate millions of jobs, and we can do the same again. All we need are clear policies, clearly explained to people. Our overall priority is to grow and to create employment, and that should be the task not just of the government, but everybody.

- You tend to identify with the small business owner...

- I identify with entrepreneurs, even if it is a bar owner who only provides work for one other person. We need big companies, but we also need small businesses. The most successful regions of Spain are those with the most small businesses; we need to spread that approach, and one way to help is by cutting red tape. Entrepreneurs have an impossible time dealing with so much bureaucracy. We have state housing organizations operating at national, regional, and municipal levels, all overlapping, and in the end, people go to a private agency. There are too many rules and regulations in this country, and many of them are ignored. We need fewer rules, but ones that are respected.

Rajoy will have his work cut out keeping the PP's hard right under control: at times over the last four years it has seemed more interested in getting rid of him than the Socialists. In power, there is the ever-present danger that if it doesn't get its way, it will again turn its guns on the leader. "But Rajoy has shown that he is able to act independently from pressure groups in very difficult situations," says one senior party leader.

If the polls are not wrong, in less than two months this quietly spoken man, with his old-fashioned, provincial manners and politeness, will finally get the opportunity to show whether, as his supporters insist, it is true that "Mariano will make a better head of government than leader of the opposition." It has been a long and hard road.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.