One man's mission to keep Malaspina's legacy alive

Manfredi discovered the explorer at a used book stall; he never looked back

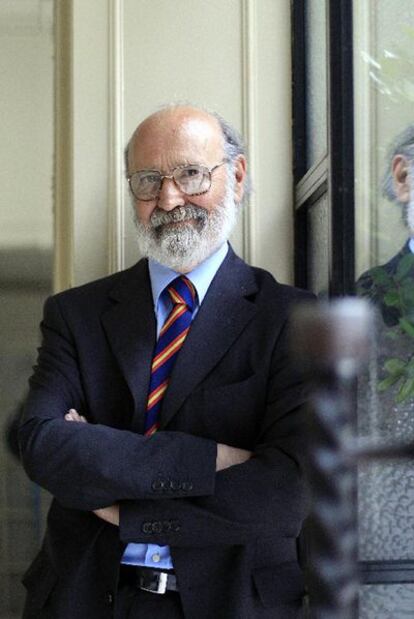

"We can speak in Spanitalian - or Italiañolo, as Malaspina called it," says Dario Manfredi. But in fact, he speaks almost perfect Spanish. "Except for menus," he says as he opens one. "The names of dishes are often indecipherable to me."

Manfredi is considered the world's leading expert on Alessandro (Alejandro) Malaspina, the Italian who in 1789, two weeks after the French Revolution broke out, and as an officer of the Spanish Royal Navy, set out on a circumnavigation of the world. He returned after five years. A little later he was accused of treason and spent seven years in prison, until he was at last released and sent back to Italy, where he remained for the rest of his days.

"The deeper I got into his story the more I liked it, on account of his genuine and strong character. His voyage around the world was not an expedition; it was a symphony."

It is impossible even to jot down all of what this affable man has to say about Malaspina, a man as little celebrated in his native land, Italy, as in his country of adoption, Spain. He must have been a real Italiañolo, and not only in his language. One of Manfredi's several books about him is titled Italiano en España, español en Italia (or, an Italian in Spain, a Spaniard in Italy).

"About 40 years ago I found a book about Malaspina in a used book stall in Rome, and in four hours on the train to La Spezia [where he lives] I read it, and was fascinated."

Manfredi denies being a historian, dismisses his life as a small businessman, being now retired, and expatiates on what he considers his passion: "Alejandro," as he breezily calls him after 40 years of familiarity.

Manfredi was recently in Madrid at the invitation of the BBVA Foundation, to present Las corbetas del Rey (or, The King's corvettes), a book by Andrés Galera on the Malaspina voyage. "This is the only work," he says, "that does not contain one single historical error." Over the years he has collected countless letters and documents, kept mainly in the Alejandro Malaspina Foundation, over which he presides. Manfredi is 70 and misses his late wife - who also liked Alejandro, and helped him in his research - and goes on speaking of Malaspina, with none of the pedantry one often fears in a scholar.

"He was a reformer. He saw that Spain could not go on governing America without even knowing it, and with such a centralized system. He thought that there had to be reforms; not a revolution, but changes. Seeing himself as a Spaniard, he felt that he had to set his ideas before the king. But by the time he returned, the situation had changed greatly in Spain, and he failed to see this." He was accused of treason, convicted and jailed by the all-powerful royal favorite Godoy.

The present Spanish scientific expedition Malaspina 2010, which is about to complete its oceanic fact-finding voyage around the world, is a venture that he finds very interesting, "though science has advanced so much in two centuries, that it can bear little resemblance to that of Alejandro."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.