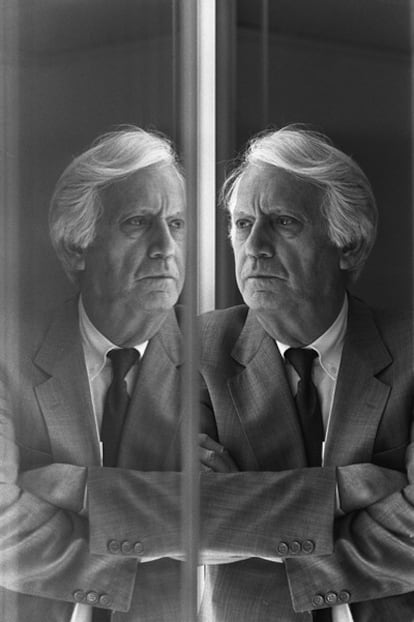

Jorge Semprún: the memory of the 20th century

Spanish Civil War exile survived Buchenwald and achieved literary success in France

The loss of Jorge Semprún entails the loss of the memories of prisoner number 44,904, his identity at Buchenwald, where he spent 16 months between the ages of 20 and 22. Semprún built his literary oeuvre with fragments of his own memories of this defining period of his life, although it would be two decades before he decided to address the topic in writing.

"I have more memories than if I were a thousand years old." These words by Charles Baudelaire, which Jorge Semprún borrowed for one of his books, aptly describe the life of a man whose more than eight decades of existence can be traced back in his narrative work.

Key moments of his life can be reconstructed by reading books such as Adiós, luz de veranos... (or Goodbye, light of summers), which recalls his teenage years in exile during and after the Spanish Civil War, when his family moved first to The Hague and then to Paris. His work for the French Résistance and his experience at Buchenwald are captured in The Long Voyage, That Sunday and above all Writing or Life. His 1964 expulsion from the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), for which he had worked for so many years, is described in Autobiography of Federico Sánchez. The pseudonym he used while working as an undercover agent in Franco's Spain served to title another book about his stint as culture minister between the late 1980s and early 1990s, Federico Sánchez takes his leave from you.

A grandson of the conservative politician and Spanish statesman Antonio Maura, Jorge Semprún was born in Madrid on December 10, 1923 into a wealthy bourgeois family. His mother died before he turned eight, and when war broke out in 1936, he and his siblings traveled to The Hague with their father, who was Spain's ambassador there. In 1939 the family moved to Paris, which became the writer's adopted home. In his texts about that period, Semprún included an anecdote about the time he was made fun of at a bakery because of his poor accent, and how he resolved to eliminate all foreign taints in what would eventually become his main literary language.

During World War II he joined a unit of the Résistance that answered to London. In September 1943, at age 19, he was arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Buchenwald camp, where he was registered as a stucco craftsman rather than a student, thereby possibly saving his life. Semprún worked in the camp administration and some controversy exists over his exact duties. His own brother Carlos, an early communist like himself who later veered towards the right and became estranged from Jorge, accused him of being a kapo who selected the inmates who would be sent to almost certain death. He always denied this.

In a 2007 interview with The Paris Review, he said: "What was the Résistance's ethic in the camps? Should we have used to our political advantage the responsibilities the SS delegated to the deportees when they allowed us to administer the camp at Buchenwald? This is a fundamental moral question. The chief of the SS work unit orders the kapo of the prisoner command, 'The day after tomorrow, Thursday, at six o'clock, I need three thousand men assembled in the yard to be sent to Dora.' The kapo consults with me, and I know that Dora is a harsher camp, where these men will likely die - so what do I do? Should I answer, 'No, I do not want to select three thousand men, they are all my comrades, I cannot choose?' The idiot who says this is shot on the spot, and there will still be three thousand men chosen the following morning at six o'clock. The choice is not between three thousand prisoners and no prisoners at all. The choice is as follows: either the SS will make the selection or we will do it in their place, thereby using the process to save some prisoners."

The importance of this experience is captured in a 2001 interview with EL PAÍS, when Semprún explained that a French friend once asked him whether he was really Spanish or French. And he simply replied: "I am a Buchenwald deportee." After his liberation, Semprún became an active member of the PCE, working under the cover of a job as a translator at UNESCO, which allowed him to travel to Spain and organize the underground resistance against Franco. But mounting discrepancies with the official party line got him expelled in 1964. His book about that experience earned him the 1977 Planeta Award.

Although Semprún spent most of his life in France and wrote most of his work in French, he never renounced his Spanish nationality, a fact which prevented him from being admitted into the Académie Française, although he did become a member of the Académie Goncourt. He also wrote scripts for the French-Greek film director Costa-Gavras, earning an Oscar nomination for his 1969 screenplay, Z.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.