Wolves test appetite for conservation

Protection measures have brought the species back from the brink of extinction, but now Castilian farmers say they are paying a heavy price

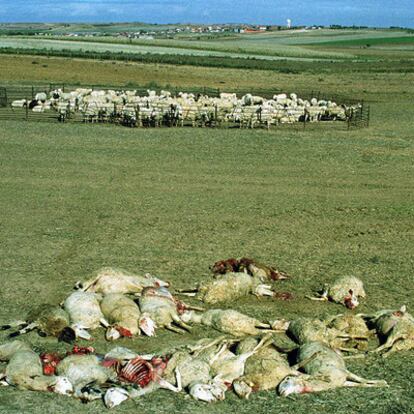

"What are you doing with la chata [the snub-nosed one]? Put that down right now; you don't even have a gun license!" yelled Julián, a 45-year-old sheep breeder, to his son Daniel, 25. It was night-time and wolves were attacking their flock just a few kilometers north of the walled city of Ávila. The young man's initial reaction was to pick up the weapon, but his father reminded him of the legal limits: gone are the days when killing a wolf was cause for celebration.

The animal, which in Spain was nearly wiped out in the 1970s, became a protected species in the 1980s. But their survival came at a cost: the sheep and cattle that serve as their food. And this fact has breeders up in arms.

"They tell us we must put up with the wolves, but you can't put the fox in the same pen with the chickens," says Jesús Veneros, of the agricultural workers' union UPA. This is a common lament south of the River Duero, the frontier between northern territory where wolves may be hunted and protected areas in the south where they may not. This artificial border has not been changed since its establishment in 1992, as part of the European Habitat Directive, even though the species has since recovered notably on the central Castilian plateau.

"These days, the wolf is far from being an endangered species in Castilla y León," says José Ángel Arranz, chief of environmental affairs in the region that includes the province of Ávila. "In order to preserve the species, all we need to do is to reduce its conflictive side." Or in other words, to keep its predatory instincts in check.

"So they want wolves around here? That's fine, but let them provide the food," says Mari Ángeles, 37, owner of a cattle ranch in Mengamuñoz, also in Ávila, that she inherited from her father. Her husband Jacinto takes care of the cows while she runs a restaurant in the same town "to make ends meet."

There are another 22,000 sheep and cattle spreads in Castilla y León, representing nearly three million head of stock, according to figures provided by the senator for Ávila, Antolín Sanz, who underscores the importance of this sector for the regional economy.

Mari Ángeles voices her concerns in the restaurant's dining room, where a circle of people has formed around her. She is angry but has not lost her sense of humor yet. "These wolves, besides killing off the herd, are going to do for my marriage, too." For weeks now, Jacinto has given up on the family dinner to make the rounds with a group of colleagues each night, in an attempt to prevent further wolf attacks.

In Spain, statistics relating to the damage caused by wolves are far from reliable and tend to be based on estimates or extrapolations. In 2010, 709 head of cattle died in Castilla y León, according to regional authorities, who estimated the cost at 202,395 euros. For their part, the unions UPA and COAG raise that figure to 500,000 euros and argue that 2,750 animals were killed by wolves. Neither the numbers nor the interests seem to match.

Green groups like Ecologists in Action or the Association for the Study and Conservation of the Iberian Wolf (ASCEL) agree with the breeders that better compensation schemes need to be set up, but they also underscore that the economic impact of wolves is very limited, and that only 0.06 percent of all cattle sustain attacks, according to Javier Talegón of ASCEL.

"It's true that breeders have certain expenses that French breeders, for instance, do not because there are barely any wolves in France," admits Arranz, of the regional government. "We are trying to turn wolves into an added value that will invigorate rural areas."

In the event of repeat attacks, the forest patrols under Arranz's direction ask for permission to shoot down the specific animal that is behind them. "This has happened in very isolated cases, perhaps five or six times in 2010," he says.

"The wolf, lacking large prey in our mountains, has no choice but to steal meat. And man defends his meat. When will the war between man and wolf end?" asked the late Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente in one episode of his popular documentary series El hombre y la Tierra, aired by Televisión Española in the late 1970s. Back then, the war was very real: there were still alimañeros around, vermin-hunters who plied their trade to survive postwar poverty, but whose efficient work led to the near-extinction of the species. Wolves disappeared entirely from many parts of the Iberian Peninsula.

More than 30 years after the death of Rodríguez de la Fuente in a plane crash, the recovery of the species is an undisputed fact in Catalonia and also south of the Duero. But the prey that wolves used to feed on are scarcer than ever before, and this is pushing new wolf colonies to seek out food where it is plentiful and easy to obtain: out in the fields where the flocks graze.

In Castilla y León, cattle must be insured in order to receive compensation in case of a wolf attack. It is not expensive — about three euros per head- but it only covers dead animals. There is no compensation for sheep or cows that survive an attack and stop giving milk or abort their lambs or calves because of post-traumatic stress. Breeders in the region would prefer to get direct compensation from regional authorities as they do in Asturias, where wolves were never quite extinct.

But such compensation systems are not devoid of subterfuge. A 2009 study estimated that 15 percent of claims were false, and that many alleged wolf attacks can actually be attributable to wild dogs. Environmental groups say that this creates a different type of danger: "Wolf management gets distorted. The wolf is presented as a more dangerous animal than it really is, and the media pick up on that," says Talegón of ASCEL. This may be the case, but the fact remains that shepherds and cattle ranchers have been living on edge ever since wolves returned to their former hunting grounds.

Near Jacinto's herd, at the foot of a tree, an old tape recorder breaks the silence. For over a month now, the pastures are neither quiet nor fully dark at night. Jacinto and his colleagues light bonfires, shoot their guns up in the air and renew the batteries on the old cassette player in the hopes of keeping the wolves at bay.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.