Miró: the rebellion of a pyrotechnic colorist

Works by the Catalan have taken over London's Tate Modern, in a retrospective that includes more than 150 pieces and examines the ethical commitment of the artist

The step, a recurring motif used by Spanish artist Joan Miró (1893-1982), allowed him to connect the concrete with a personal universe made up of abstractions, inhabited by imaginary symbols and vivid colors. La escalera de la evasión, a work he painted in 1940 while in exile in a France gripped by fear because of the advancing Germans, also expresses the need for escape from a dark social and political reality.

Under the same title, The Ladder of Escape,the first big retrospective of the artist in London for 50 years investigates the artistic key of a genius of modern painting, as well as his commitment in one of the most turbulent times in European history.

Organized by the Tate Modern in collaboration with the Fundació Joan Miró de Barcelona, the exhibition opens to the public today, complete with an impressive collection of 150 paintings, drawings and sculptures that reflect the evolution of his formal characteristics and thematic inspiration.

It is the first big retrospective of the Catalan artist in London for 50 years

Also on show are the commitments he made to political causes, such as the posters he created supporting the Spanish Republic, his domestic exile under the Franco dictatorship and the aggression of his later works when the regime was in its dying stages.

In the early 1920s, the Barcelona-born painter, who was drawn to Paris by the new trends in the art world, tried to distill the essence of his Catalan identity with symbolic, evocative and meticulous painting, as seen in La masía (1921-22), a work inspired by his parents' house in the Tarragona countryside.

The influence of the surrealists in the French capital and his strong links with poets such as Paul Éluard, are reflected in works such as Paisaje catalán (1923-24) and the sequence Cabeza de payés catalán (1924-25), which the Tate Modern exhibition has managed to more or less bring together in its entirety.

The events of the following decade, with the breakout of the Civil War and the arrival of totalitarian powers in Europe, prompted the return to a realism with dramatic touches. In Naturaleza muerta con zapato viejo, mundane objects such as a knife stuck in an apple, a hunk of bread and a bottle that amplifies the light of the night, revolve around "tragic symbols from this period, although I did not know that then," Miró would say years later.

This iconoclastic still life dates from 1937, the same year the artist completed El segador (Payés catalán en revuelta) for the Spanish pavilion at the Paris Universal Exhibition. More than 70 years later, the show has to make do with an enormous photo of Miró working on that piece, given that it has been lost. It was shown in the French capital, together with Guernica by Picasso, who was Miró's mentor in his first Parisian era and a friend until the Málaga-born artist died in 1972.

Miró later played the same role of Parisian compass for a younger Salvador Dalí, but their distant stances in the following years eventually led to a break in their relationship.

During those years, Miró was the author of politically charged works such as Aidez l'Espagne (Ayudad a España), but it was his more intimate and disturbing reactions - expressed in the celebrated Constelaciones from 1940 - that underline why he later became such a giant in the art world.

In May of that same year, he carried those very canvases under his arm from Normandy toward Spain in an effort to escape the Nazis. While Picasso vowed never to return to his homeland until Franco had died, Miró opted to shut himself away in a studio in Palma de Mallorca, while his name - practically invisible in the Spanish art world - gained weight on an international level as an exponent of post-war abstraction.

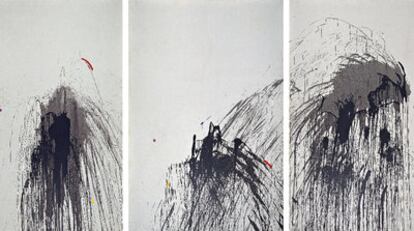

He evaded all the attempts at rapprochement by the Francoist authorities, and, by the time he was a septuagenarian, saw himself swept along by the spirit of rebellion that marked the end of the 1960s. The Miró that captured that atmosphere in works such as Mayo 1968 actually went as far as setting fire to his Lienzos quemados, which are hung today in the Tate Modern as they were at the first exhibition in Paris, in 1974. One year before, he had characterized the last death throes of the dictatorship in La esperanza del condenado a muerte (1973), dedicated to the anarchist Salvador Puig-Antich, who was shot by the regime.

One of the achievements of the exhibition - which, after London will travel to Barcelona (October) and then Washington, D.C.'s National Gallery of Art (2012) - is the rejection of the argument that Miró's work lost its bite in the later years, according to Teresa Montaner, curator of the Joan Miró Foundation. The five large-scale triptychs, which are brought together for the first time in the Tate, prove her right. They show, all at the same time, the political Miró, the abstract expressionist, and the maestro of pyrotechnic colors, a craftsman of euphoric explosions of paint.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.