Civil War strategists join combat

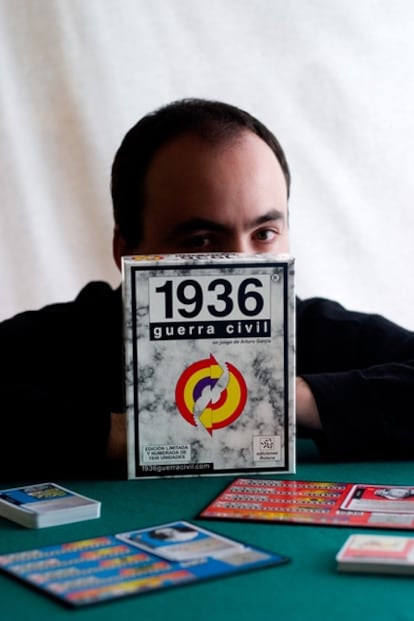

Spain's conflict can be fought anew with the board game '1936 Guerra Civil'

It's happening all over again. The Republicans have capitulated in Maestrazgo, cutting the loyalist Mediterranean area in two, and Madrid is under siege from the Nationalist forces. But Franco is not at his military command in Burgos. Nor is the Republic's war cabinet sitting. No, we are in the Generación X comic and gamers' shop in Puebla street, in the capital's Malasaña neighborhood, one of the places where 1936 Guerra Civil is on sale, and this journalist, supposedly the Republican strategist, is getting a pretty solid beating from the game's creator, Arturo García.

"The Nationalists always start the game," says this telecommunications engineer, who began working on the project in 2000, spending six years on it before it was finally ready to be manufactured. The detail seems logical, seeing as it was the rebel army officials whose attempted coup d'état plunged Spain into conflict in 1936. Indeed, this is the essential point of García's creation: history can be altered through the playing of his game, but only thanks to a complex interplay of the elements that made the Spanish Civil War one of the key episodes of 20th-century history.

"The game is against simplification. It wasn't just fascists versus communists"

The Nationalist side chooses leader once, while the Republican is free to change

"There were other games about Spain's Civil War," he explains. "But they were focused entirely on the military aspect, with maps and so on. Our Civil War was more than just battles." García explains that his idea was to make the game "balanced but asymmetrical." Either side can win, but only by making use of the personalities and strengths - military, political, economic and diplomatic - that the two sides could count on at the time.

For example, the Nationalist player can only choose a leader once, with the benefits that redound to his score via a complex points system from having a designated chief. The Republicans, however, have the capacity to change supremo as the different options come up on the cards, reflecting the ideological and democratic flux that existed on the losing side during the three-year war.

García has gone to great lengths to express the complexity of the two sides, from the genuinely radical fascists of the Falange to stuffy monarchists within Nationalist ranks, and the dizzying variety of political strains - from liberal republicans to hardcore anarchists and communists - on the other. The different forces have different kinds of impact on the game: militia forces are easier to mobilize due to their "enthusiasm" ranking, while at one point García opts to put Alfonso XIII back on the throne using the influence gained from playing the Abc conservative newspaper card.

"This game is against simplification, both now and then. It wasn't a simple conflict between fascists and communists and the game makes the distinctions within the two sides visible," García says. "On the winning side, many ended up as losers," he adds, citing the examples of Falangists and monarchists.

He was particularly drawn to the imagery that came out of the conflict, taking place as it did at a time when photography was becoming a highly developed documentary form, but with poster art still a major force in the popular imagination. Having combed through the major Spanish archives, seeing tens of thousands of images from the period, García brought together at least 1,000 in his personal collection, of which 252 are used in the game's equipment as produced by Cartamundi, a leading international manufacturer of card games. He stresses that he has meticulously credited the source of all the visual material used, in contrast with other previous efforts to create a game-playing experience out of Spain's bloody conflict.

Besides imagery, García drew on his "passion" for Civil War history and contacted authorities on the subject in order to get "feedback" on his game project. British historian and Franco biographer Paul Preston, for example, was on hand to assess 1936 Guerra Civil. "He encouraged me a lot," García recalls. "And he helped with the odd detail."

García is clear about one thing, however. Much as he appreciates the freedom he was able to enjoy in his solo project, he would not finance another game himself, having spent four years promoting the final product and still barely managing to have broken even on the deal. But, he acknowledges, he has been free to control all aspects of the product, making the number of cards and features exact multiples of the magic number, 36. And the price? Thirty-six euros. "That's the advantage of producing it yourself," he says.

García also admits that the fact that 1936 is a board game, with marginal impact in media circles, has helped to avoid controversy, or having to explain why it is legitimate to use the tragic history of Spain to create entertainment. Certain video games, he notes, have run into trouble in a country where the conflict is still largely a taboo subject, despite the flaring up of public debate over historical memory after Prime Minister Zapatero came to power in 2004, and announced an initiative to give moral redress to those who ended up on the losing side.

Back in our game, and with García giving the Republican side more than a helping hand - perhaps out of sympathy for the novice sitting in front of him or because of his own natural sympathy toward the legitimate government of 1930s Spain - the Republicans are staging a dramatic comeback. The decision to attack Madrid by the Nationalists proves a fatal error ("the communists are better at defending than attacking"), the Republicans build up morale with a simple victory at Toledo's Alcázar and end up pulverizing Franco's forces at Brunete for total victory. This journalist's prime minister, Fernando de los Ríos, did not live to see the Republic's triumph, but the dream of democracy was kept alive...

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.