When Judas Priest were accused of inducing two fans to kill themselves: A chronicle of the most infamous trial in music history

In December 1985, the attempted suicides of two young people (one of whom died) was blamed on the subliminal messages supposedly contained in the song ‘Better by You Better than Me’

On December 23, 1985, two young men made a suicide pact in Sparks, a town of about 100,000 inhabitants in Nevada. That afternoon, they had been drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana and listening for six hours straight to the album Stained Class (1978) by the heavy metal band Judas Priest. At nightfall, they went to a playground next to a church with a 12-gauge shotgun. Raymond Belknap, 18, put the barrel under his chin, pulled the trigger, and died instantly. His friend, James Vance, 20, did the same but survived, although his face was disfigured.

Both Belknap and Vance came from ultra-religious and deeply dysfunctional families, plagued by alcoholism, domestic violence, academic failure, and a propensity for all sorts of addictions and petty crime. Vance had tried to run away from home 15 times, and Belknap had previously attempted suicide. He had even told his sister that he wanted to be a serial killer when he grew up, so it seemed clear that their social and environmental circumstances had sown the seeds of tragedy. But the boys’ parents didn’t see it that way, and they decided that Judas Priest were to blame.

In a letter sent from the hospital by Vance to Belknap’s mother, the survivor wrote: “I believe that alcohol and heavy metal music such as Judas Priest led us to be mesmerized.” The families decided to take his word for it and sue the British band and their record label, CBS, as responsible for Belknap’s death.

Initially, the prosecution decided to use the lyrics of the song Heroes End as evidence, but the judge dismissed this, as the lyrical content was protected by freedom of expression under the First Amendment. Then, the families’ lawyer, Ken McKenna, decided to change the argument, claiming that another of their songs, Better by You Better than Me, contained hidden subliminal messages.

According to McKenna, the band had included parts of the song recorded in reverse, causing the listener’s brain to unconsciously receive the message “Do it” repeatedly. If this was indeed the intention, it had little effect, since 500,000 people bought the record. Moreover, the song wasn’t even written by Judas Priest: it was a cover of a 1969 track by Spooky Tooth.

Metalheads on the bench

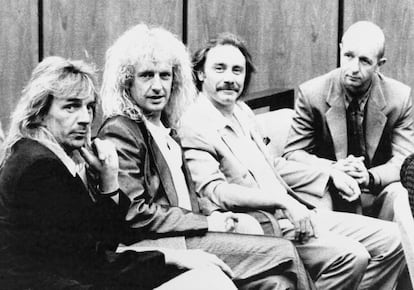

Despite all this, the lawsuit was accepted, and on July 16, 1990, the members of the Birmingham-based metal band were ordered to appear in court in Reno. The group, led by Rob Halford, had to suspend their ongoing tour to attend the trial, which lasted a month and a half and included more than 40 witnesses.

Hundreds of fans gathered outside the courthouse to show their support. Between the filing of the lawsuit in 1986 and the start of the trial, another tragic event occurred: James Vance died in 1988 from a methadone overdose. But, during the trial, his parents downplayed all the evidence pointing to a very troubled life history and even declared that, despite having had a problematic period in the years immediately preceding the suicide pact, he had “changed for the better” and embraced the Christian faith after “the garbage music” of Judas Priest had led him astray.

We’re in music for people to have a good time, not to dieRob Halford

The trial was chronicled in a documentary released in 1991: Dream Deceivers: The Story Behind James Vance Vs. Judas Priest. Even more than that, its director, David Van Taylor, began filming interviews with James Vance and his family after Belknap’s suicide. “I thought it was ridiculous. I just couldn’t believe it. I didn’t know any of the circumstances, but I couldn’t believe that someone would blame such trauma, such an event, on a record. And I had a strong suspicion that there must be other things going on in these families,” the documentary filmmaker told The Washington Post in 1992.

“I think they [Judas Priest] killed Ray. They’re murderers.” That is one of the first lines spoken by young Vance in the film, which is frankly difficult to watch when the viewer is confronted with his completely disfigured face, reconstructed after hundreds of hours of surgery, and the oppressive sense of madness and dissociation from reality that emanates from his family environment. In the interview with The Washington Post, Van Taylor acknowledged his astonishment at the fact that James and his parents were “unperturbed” by being exposed to the cameras.

The judicial investigation also extended to a recording studio, where the song’s content was analyzed line by line. Both the sound engineer and the record’s producer were called to testify. The sequences in which the recording was played backward, over and over again, in short segments of almost cacophonous noise to discern whether or not there were hidden messages, were truly bizarre. Wilson Bryan Key, the most famous expert on the use of subliminal messages in advertising — and considered by many to be a fraud — also testified. Key claimed to see evidence of subliminal messages in the song, and also recommended that it be analyzed by a sound engineer named Bill Nickloff. It was later revealed that Nickloff was, in fact, a marine biologist and did not possess the expertise he claimed.

The climactic moment came when vocalist Rob Halford appeared, impeccably dressed in a suit — a stark contrast to his usual leather and studded look — and the judge asked him if there was any subliminal content in the song, and asked him to sing it. “It was like Disneyworld. We had no idea what a subliminal message was — it was just a combination of some weird guitar sounds, and the way I exhaled between lyrics. I had to sing Better by You, Better than Me in court, a cappella. I think that was when the judge thought, ‘What am I doing here? No band goes out of its way to kill its fans,’” the Judas Priest frontman told Yahoo Entertainment in 2020.

Indeed, Judge Jerry Whitehead found no evidence of guilt in the recording, arguing that it was simply an accidental combination of sounds. But the ruling (over 100 pages long) satisfied no one. Although it acquitted the band, CBS was fined $40,000 for delaying the delivery of the required material, and Judas Priest had to pay their share of the court costs, in addition to losing the canceled dates of their tour. Timothy E. Moore, PhD, a psychologist and one of the defense witnesses, later criticized the lack of rigor in the entire process in an academic article, arguing that it relied on what he considered pseudoscience. And, most seriously, the suggestion that, although no incriminating evidence had been found, the ruling did not rule out the possibility that listening to a record could incite murder and, moreover, set a precedent. “This leaves the door open for it to happen again,” Halford declared.

For Judas Priest, it was also a blow that ultimately affected them. Quite frivolously, the entire lengthy trial cast a shadow of suspicion — both in the media and among the public — over them and on heavy metal itself. “I was furious,” Halford would later declare, “because it all went against what the band was and what it stood for. We’re in music for people to have a good time, not to die.” During the documentary, the band members also spoke about their music being “an artistic expression of the feelings of isolation and frustration that living in the modern world can generate,” and the vocalist emphasized: “Not everyone sings about love: 99% of the U.S. charts, at any given time, are love songs. We think we’re a bit more intellectual than that.”

McKenna, the prosecution’s lawyer, was also displeased with the verdict. He stated that the evidence presented was too novel for the court to fully grasp, but that in the near future, the case would be remembered like the one that demonstrated the link between cancer and tobacco use. “In five years, we will all know that this music causes violence and death among teenagers,” he asserted.

Climate of US criminalization of rock

Fortunately, McKenna’s prediction was wrong, but this story shouldn’t be considered a mere anecdote or an isolated incident. It’s deeply rooted in the social climate of that era in the United States. It’s also worth noting that, although it was the height of the Reagan era, it wasn’t something exclusive to the most conservative sectors. Judas Priest themselves had already experienced a bitter precedent with censorship. In the summer of 1985, the Parents Music Resource Center, a government agency founded by Tipper Gore (wife of Democratic politician Al Gore) and funded, among others, by Mike Love of The Beach Boys, included their song Eat Me Alive on a list called “The Filthy Fifteen,” which included songs the committee considered objectionable due to their lyrical content. This was the precursor to the creation of the now-famous “Parental Advisory. Explicit Content” labels. The curious thing about that list of infamy is that, although heavy metal songs predominated, there were also titles by Prince, Madonna, and Cyndi Lauper, questioned for their sexual content.

But Judas Priest’s case wasn’t the first time a heavy metal band had been accused of inciting suicide. In fact, it’s likely that the Vance family and David McKenna were inspired by a case that occurred a little earlier. On November 1, 1985, the parents of John Daniel McCollum, a 19-year-old who had taken his own life in Indio, California, sued Ozzy Osbourne and, again, CBS Records, arguing that his song Suicide Solution had incited the young man to take his own life. In this case, there was no trial because the content of the lyrics was not considered criminally liable. There were two other boys who killed themselves, in 1986 and 1988, apparently after hearing the song, and another lawsuit was dismissed in 1990. “It would be a pretty bad step for my career to write a song that said, ‘Pick up a gun and kill yourself.’ I wouldn’t have many fans left,” the recently deceased Osbourne stated.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.