The day the creator of Tetris met the inventor of the Rubik’s Cube: ‘We have to look for entertainment that challenges us’

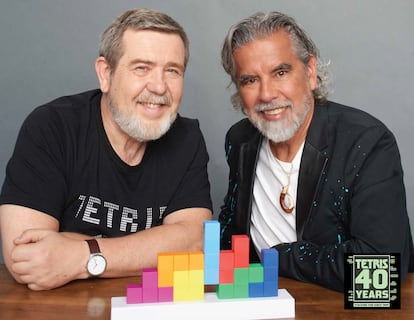

Alexey Pajitnov and Ernő Rubik had a conversation with EL PAÍS in Spain, where the video game designer received an honorary award

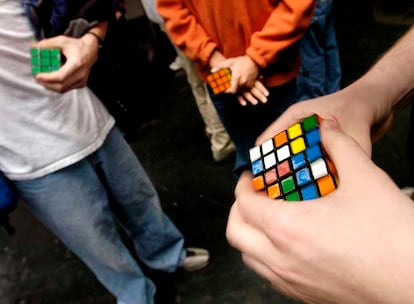

“This,” says Alexey Pajitnov, while holding a scrambled Rubik’s Cube, “is my favorite puzzle. But I also think it’s simply one of the best things humanity has ever invented. If we could only send 10 things into space, this should be one of them.”

Standing beside Pajitnov — who revolutionized the digital world when he created Tetris, the best-selling video game of all time — is the cube’s creator, Ernő Rubik, smiling widely.

Both men rarely give interviews, but they agreed to speak with EL PAÍS at the OXO Video Game Museum in Málaga, Spain. Rubik — who spends half the year in San Pedro de Alcántara, a resort town in Málaga province — visited the museum on Friday, December 5. The following day, in this temple of creative leisure — which is always packed with children — Pajitnov received an honorary award.

The conversation is a tectonic clash between two minds that know how to combine leisure, creativity and mathematical challenges. With one difference, of course: you can’t get more analog than a Rubik’s Cube… and you can’t get more digital than Tetris.

The meeting begins with each of them reminiscing about how they discovered the other’s creation: “I spent two months trying to solve it. And I did it without any help. It’s one of the greatest achievements of my life,” Pajitnov confesses, laughing.

And Rubik? How did he discover Tetris?

The cube’s creator returns the compliment: “When we released the cube in Hungary, back in 1974, it was a huge success, but obviously, many things didn’t reach my country, which was behind the Iron Curtain,” he explains. “The cube’s success allowed me to travel, buy computers and access many things that were sold in the West. I’m not that much of a digital person, but I love geometry; I saw Tetris’s potential as soon as I laid eyes on the game during a trip to New York.”

Some consider Tetris and the Rubik’s Cube to be games. Some see them as mathematical challenges, while others marvel at their design, elegance and simplicity. But beyond their functionality, these inventions have undoubtedly had a decisive impact on culture and society in the last half-century.

Rubik — an 81-year-old architect born in Budapest — invented the 9x9, six-colored cube in 1974. He initially designed it as a teaching tool to explain three-dimensional concepts to his students. In 1980, the Ideal Toy Company marketed it internationally under the name we all know it by: Rubik’s Cube. And, since then, it has become a global phenomenon, due to its simplicity, accessibility and, of course, the mental challenge that it offers. It’s impossible to calculate how many cubes (or knock-offs) have been sold, but the number of trademarked cubes alone is estimated at nearly 500 million.

Tetris, meanwhile, was created by Pajitnov, who was born in Moscow 70 years ago. In 1984, he built the game on an Elektronika 60 computer. He designed it as a puzzle based on falling geometric pieces that must form complete lines. Its international expansion began in 1988, when several companies beyond the Iron Curtain bought the license for the game. Its popularity subsequently skyrocketed after being included with the Game Boy handheld console in 1989, along with the release of other handheld devices specifically designed to play it. Since then, it has been adapted to dozens of platforms, becoming a universal classic of video games, with hundreds of versions (and rip-offs, of course), including adaptations to all kinds of devices and its leap into virtual reality.

With hundreds of millions of copies sold, Pajitnov didn’t initially receive royalties for the game, as these belonged to his employer: the government of the then-Soviet Union. He only began to obtain copyrights in 1996, when he and Henk Rogers formed The Tetris Company (TTC). Rogers — who joined Pájitnov in Málaga — walks through the halls of the OXO Museum while the interview takes place, pausing to gaze at the devices on display.

Both creations — the Rubik’s Cube and Tetris — are the epitome of mechanical elegance, as well as a demonstration of how simple artifacts can contain incredibly complex and fun dynamics. They’re like musical scores, ready to be reinterpreted by new generations.

“Looking back now,” Pajitnov reflects, “if there’s one thing I think I can be proud of, it’s that the game helped bring people closer to computers. Back then, those devices were serious things — somewhat unpleasant — and they commanded a lot of respect. And, suddenly, there was a very simple, very accessible game that people could interact with on a computer.”

A cognitive challenge in the age of convenience

There’s one word that both inventors use enthusiastically in their conversation with EL PAÍS: “challenge.” In a time when the vast majority of content consumption is passive — reels, silly videos, series watched in the background, or even news stories that end with the headline — it’s worth remembering that these two devices challenged people: they pushed them to think carefully, in order to complete the challenge they presented.

“Of course! My biggest concern today is artificial intelligence,” says Pajitnov. “It’s making people not think, not face challenges. The entertainment that challenges us is the kind that we need to seek out,” he argues, pointing to the cube on the table in front of him.

“We’ll have to see if AI ever becomes as intelligent as us,” Rubik adds, “but progress always has contradictions: a vehicle’s increased speed helps us get places faster, but it also makes accidents more serious. Everything has positive and negative effects.”

“You get your sweet, but you get to pay!” Pajitnov exclaims.

Rubik elaborates: “AI seems to have come to conquer nature. Well, that’s impossible. What we have to ensure is not that AI is better than us, but rather that this technological revolution provides solutions to our problems. It’s that simple.”

“And that it helps us think not more individually, but as a society,” Pajitnov adds.

“You have to discover what’s best about your idea,” Rubik reflects. “And trying to find the perfect solution is complicated: almost everything can be refined and improved. The greatest discovery, really, is pointing to a direction: pointing out where we should be heading. Trying to instill a mindset in people that motivates them to achieve big goals.”

When asked what’s the strangest situation in which they’ve seen someone playing Tetris or trying to solve a Rubik’s Cube, Pajitnov has a clear answer: “Many heads of IT companies have confessed to me that they used to install viruses on their employees’ computers to delete Tetris if they installed it,” he laughs.

And what would they say to a young creative who has to navigate this uncertain 21st century? “The only advice I can give is to listen to yourself. Never pay attention to what marketing or trends tell you. Look for what makes you happy,” Pajitnov says with conviction.

For his part, Rubik has two pieces of advice: “First: be curious.” Throughout the conversation, Rubik has extolled the innate, almost childlike curiosity that — according to him — should guide human behavior. “And second, never give up when you’re facing a serious problem. If you can’t solve it, perhaps it has no solution, but if you tackle it, you may realize that you can improve enough to solve it.”

Such a lesson couldn’t be better crystallized than in these two artifacts. Tetris and the Rubik’s Cube — kings of the digital and analog worlds respectively — will surely continue to entertain (and challenge) people for many decades to come.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.