History’s greatest art thefts: From the Mona Lisa to a priceless Vermeer

Sunday’s robbery at the Louvre is just the latest in a long line of spectacular heists that have taken place around the world over the course of the years

The theft on Sunday of nine jewels from the collection of Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie at the Louvre Museum is just the latest in a long line of incredible art robberies. In fact, this isn’t the first time the Louvre Museum has suffered an art heist, starting with the theft of the legendary Mona Lisa painting.

La Gioconda, also at the Louvre

In 1911, the Louvre suffered a spectacular theft. A former employee, Vicenzo Peruggia, knowing that there were few security measures in place, entered the building at 7 a.m. on Monday, August 21, while the institution was closed. He climbed a ladder and took down “La Gioconda,” better known as the Mona Lisa, then left the premises with the treasure under his work coat. Nobody noticed until the next day. More than two years later, police caught Peruggia in Florence trying to sell the painting. Incidentally, this month marks the 100th anniversary of Peruggia’s death.

In 2021, two pieces of 16th-century armor stolen from the Louvre in 1983 were recovered and are now on display in the Richelieu Wing’s Objets d’Art room. They are a Burgundy-style helmet and an iron breastplate with relief decoration and gold inlay, made in the Milan region in the second half of the 16th century. They were stolen on May 1, 1983, when the display case in which both works were displayed was discovered smashed. The pieces were recovered in 2021 when an antiquities expert was hired to process an inheritance in Bordeaux, and both were included in the lot.

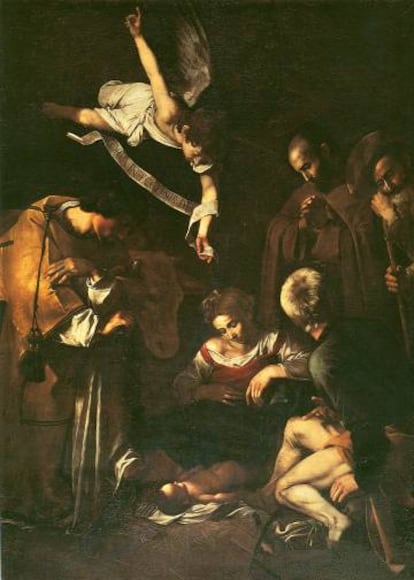

Caravaggio’s ‘Nativity’ in Palermo

It happened in 1969. Two Mafia hitmen entered the oratory of the parish of Saint Lawrence in Palermo on a rainy October night. When they emerged, only the frame of Caravaggio’s Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence, a work valued at $20 million, remained. The canvas had been ripped off with a razor blade. In 2018, a repentant member of the Badalamenti clan, Gaetano Grado, explained before the parliamentary anti-mafia commission that the entire Mafia elite first gathered around the painting, in a gesture of showing off the prestige and power they were capable of, and then took it abroad, fragmented into pieces, to be sold on the black market. Don Tano Badalamenti told Grado that he had cut the canvas, measuring 2.68 meters by 1.97 meters, into six or eight pieces to sell it on the black market, according to his version.

Munch’s ‘The Scream’... twice

On February 12, 1994, Paul Enger needed less than a minute to enter the National Gallery in Oslo and climb a wooden ladder to the Munch Room. He opened the window, cut the cable holding The Scream and fled. He took advantage of the Winter Olympics and left a sign for the police: “Thank you for the lack of security.” The thief was arrested in a hotel with the artwork.

On August 22, 2004, it happened again with another version of The Scream. At 11 a.m., two thieves gained access to the crowded gallery in Oslo’s Munch Museum, where The Scream and a Madonna by Munch were hanging. Both were recovered in 2006, although by then the moisture damage to the great Expressionist icon — there are four versions of it, painted between 1893 and 1910 — was already irreversible. The first version of The Scream is owned by the National Art Museum of Norway and is the most frequently reproduced. Two more versions are housed in the Munch Museum in Oslo, one of which was the subject of this theft. The fourth painting, the only one not owned by the Norwegian government, broke a Sotheby’s record when it was auctioned in May 2012 and sold for more than €98 million ($114 million) to American investor Leon Black.

‘The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb,’ the Van Eyck brothers’ Ghent altarpiece, is one of the most stolen artworks in history

This 1432 masterpiece, a 3.5-meter-high by 4.6-meter-wide altarpiece on display inside Ghent Cathedral, has been the target of looting, war booty and theft. First in 1794, when Napoleonic troops took the central panel to display it in the Louvre. It was eventually returned.

In 1816, six panels were sold under mysterious circumstances. On April 10, 1934, two panels were stolen again by men in black who left a note: “Pris à l’Allemagne par le traité de Versailles (Taken from Germany by the Treaty of Versailles).” One of the panels was found, although the one of John the Baptist remains in an unknown location (a copy is on display in the collection).

Finally, in 1942, Hitler took the polyptych on a whim. The Nazis hid it in a salt mine, and it was recovered there by the Monuments Mens and Women Foundation, the Allied brigade of military art experts who salvaged what they could from the Nazi looting.

Thirteen masterpieces stolen in Boston

It is considered the largest theft in history. In the mid-1980s, a wave of robberies began in Boston, linked to two groups of the local mafia. A member of one of these groups attempted to carry out a daytime robbery in the middle of that decade at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, but was unsuccessful, although it did highlight the institution’s security problems. Then, on March 18, 1990, 13 masterpieces by Vermeer, Rembrandt, Manet and Degas were stolen from the museum.

A pair of individuals disguised in police uniforms and sporting fake mustaches broke into the museum in the early hours of the morning. They tied up the guards and wandered through the galleries for 81 minutes. The art robbery of the century might not have happened if not for a series of catastrophic coincidences. The main one was that the most senior night watchman wasn’t working that night.

“He wouldn’t have let the [disguised] police officers in,” a worker recounted in This Is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist, a Netflix series about the theft. Among the stolen works was Vermeer’s The Concert, still considered the world’s most valuable unrecovered work of art. The reward offered for its return is €9 million ($10.5 million), the highest in history. The museum is keeping the empty frames on display.

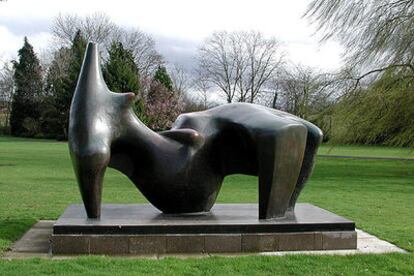

Henry Moore sculpture missing in north London

On a December night in 2005, a gang stole Reclining Figure (1969-1970) by Henry Moore. The theft is surprising because the piece measured 3.5 meters long and, more importantly, weighed 2.1 tons. The bronze sculpture was stolen from the gardens of the Henry Moore Foundation (in the town of Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, north of London) that bears his name by three thieves-workers. It took them 10 minutes to steal the piece, with the help of a truck and a crane. The sculpture has never been recovered and is believed to have been melted down.

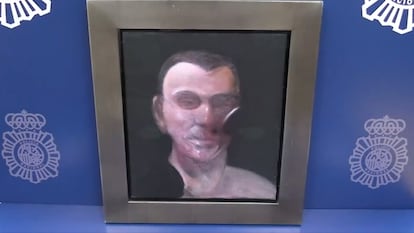

The Francis Bacons stolen in Madrid

The robbery occurred in the summer of 2015 at the home of José Capelo, a friend of Francis Bacon, in Plaza de la Encarnación, next to the Senate, in one of the safest areas of Madrid. The thieves stole five portraits that the Irish painter had given to his friend as an inheritance and which decorated his master bedroom. The oil paintings are valued at €30 million ($35 million). Three of them were recovered in 2017 and a fourth in 2024. The gang behind the robbery included an art dealer, fences and jewelers from Madrid’s Rastro flea market, as well as an Uber driver. Since 2015, the five paintings passed through different hands in failed attempts to sell them, and were gradually recovered. The last one was found after the arrest in February 2024 of two people responsible for storing the two stolen paintings that remained unaccounted for. The fifth one is still missing.

The Golden Helmet of Coțofenești and three other Dacian pieces, in The Netherlands

On January 24, 2025 four archaeological masterpieces from Romania were stolen from the Drents Museum in Assen. The robbery included a spectacular detail: explosives were used. The stolen pieces were the Golden Helmet of Coțofenești (discovered in 1928, it is made of solid gold, weighs about 770 grams, and is almost intact except for the calotte, the part that covers the cranial vault) and three women’s bracelets made of the same metal, which were part of an exhibition of more than 50 pieces dedicated to the ancient kingdom of Dacia. Around 3:45 a.m., there was a powerful explosion. The shock wave broke the glass in several windows, and the surrounding buildings were also damaged.

According to the police, who gave a press conference the following morning, there were “several people involved, and the theft was well-planned.” Speaking from Romania, Ernest Oberlander-Tarnoveanu, director of the National History Museum in Bucharest, was hoping the objects would be returned. “It’s my only hope. They are so important that it’s impossible to sell them.” Nothing further has been heard since.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.